A novel thought-controlled prosthesis for amputees

November 30, 2012

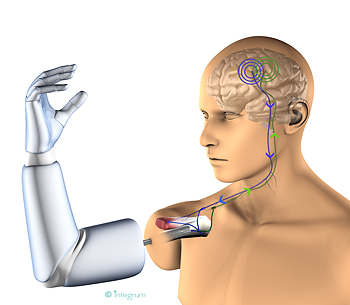

Thought-controlled prosthesis (credit: Integrum)

An implantable robotic arm controlled by thoughts is being developed by Chalmers University of Technology industrial doctoral student Max Ortiz Catalan in Sweden.

Ever since the 1960s, amputees have been able to use prostheses controlled by electrical impulses in the muscles, their functionality is limited because they are difficult to control, according to Catalan.

Today’s standard socket prostheses, which are attached to the body using a socket tightly fitted on the amputated stump, are so uncomfortable and limiting that only 50 percent of arm amputees are willing to use one at all, he says, and “all movements must by pre-programmed.”

So he developed a new bidirectional interface and a natural, intuitive control system. It uses a Brånemark titanium implant, which anchors the prosthesis directly to the skeleton through what is known as Osseointegration (direct connection between living bone and the surface of a load-bearing artificial implant). This allows for permanent access to the electrodes that we will attach directly to nerves and muscles.

Controlling the prosthesis by thought

Currently, to pick up electrical signals to control a prosthesis, electrodes are placed over the skin. The problem is that the signals change when the skin moves, since the electrodes are moved to a different position. The signals are also affected by sweat, since the resistance on the interface changes.

In this project, the researchers are planning to implant the electrodes directly on the nerves and remaining muscles instead. Since the electrodes are closer to the source and the body acts as protection, the bioelectric signals become much more stable.

Osseointegration enables the signals to reach the prosthesis. The electrical impulses from the nerves in the arm stump are captured by a neural interface, which sends them to the prosthesis through the titanium implant. These are then decoded by sophisticated algorithms that allow the patient to control the prosthesis using his or her own thoughts.

In existing prostheses, amputees use only visual or auditory feedback. This means, for example, that you have to look at or hear the motors in the prosthesis in order to estimate the grip force applied to a cup if you want to move it around. With the new method, the electrodes stimulate the neural pathways to the patient’s brain, in the same way as the physiological system. This means that the patient can control his or her prosthesis in a more natural and intuitive way.

“Many of the patients that we work with have been amputees for more than 10 years, and have almost never thought about moving their missing hand during this time,” says Catalan.