A space-time crystal clock that will last forever

September 25, 2012

Imagine a clock that will keep perfect time forever, opening new dimensions into quantum phenomena, such as emergence and entanglement (credit: Berkeley Lab)

Imagine a clock that will keep perfect time forever, even after the heat-death of the universe — a four-dimensional “space-time crystal” with periodic structure in time as well as space.

With such a 4D crystal, scientists would have a new and more effective way to study how complex physical properties and behaviors emerge from the collective interactions of large numbers of individual particles, the “many-body problem” of physics. A space-time crystal could also be used to study phenomena in the quantum world, such as entanglement, in which an action on one particle impacts another particle, even if the two particles are separated by vast distances.

Space-time crystal design

A space-time crystal has only existed as a concept in the minds of theoretical scientists — until now. An international team of scientists led by researchers with the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has proposed the experimental design of a space-time crystal based on an electric-field ion trap and the Coulomb repulsion of particles that carry the same electrical charge.

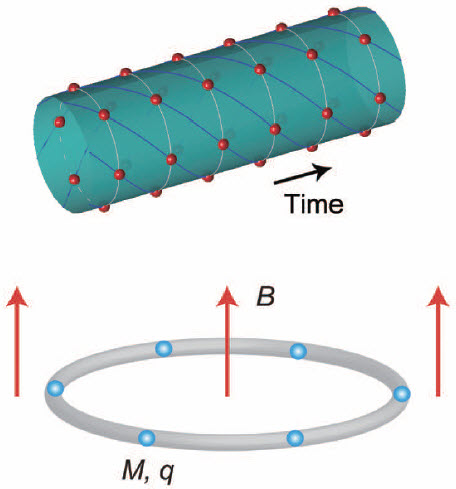

A possible structure of a space-time crystal with periodic structures in both space and time. The particles rotate in one direction even at the lowest energy state. Ultracold ions are confined in a ring-shaped trapping potential in a weak magnetic field. The mass and charge of each ion are M and q, respectively. The magnetic field is B. (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

“The electric field of the ion trap holds charged particles in place and Coulomb repulsion causes them to spontaneously form a spatial ring crystal,” says Xiang Zhang, a faculty scientist with Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division who led this research.

By applying a weak static magnetic field, this ring-shaped ion crystal will begin a rotation that will never stop. “The persistent rotation of trapped ions produces temporal order, leading to the formation of a space-time crystal at the lowest quantum energy state.”

Because the space-time crystal is already at its lowest quantum energy state, its temporal order — or timekeeping — will theoretically persist even after the rest of our universe reaches entropy, thermodynamic equilibrium or “heat-death.”

Zhang, who holds the Ernest S. Kuh Endowed Chair Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of California (UC) Berkeley, where he also directs the Nano-scale Science and Engineering Center, is the corresponding author of a paper describing this work in Physical Review Letters (PRL).

The concept of a crystal that has discrete order in time was proposed earlier this year by Frank Wilczek, the Nobel-prize winning MIT physicist. While Wilczek mathematically proved that a time crystal can exist, how to physically realize such a time crystal was unclear.

Zhang and his group, who have been working on issues with temporal order in a different system since September 2011, came up with an experimental design to build a crystal that is discrete both in space and time — a space-time crystal. Papers on both of these proposals appear in the same issue of PRL (September 24, 2012).

Traditional crystals are 3D solid structures made up of atoms or molecules bonded together in an orderly and repeating pattern. Common examples are ice, salt and snowflakes. Crystallization takes place when heat is removed from a molecular system until it reaches its lower energy state. At a certain point of lower energy, continuous spatial symmetry breaks down and the crystal assumes discrete symmetry, meaning that instead of the structure being the same in all directions, it is the same in only a few directions.

“Great progress has been made over the last few decades in exploring the exciting physics of low-dimensional crystalline materials such as two-dimensional graphene, one-dimensional nanotubes, and zero-dimensional buckyballs,” says Tongcang Li, lead author of the PRL paper and a post-doc in Zhang’s research group. “The idea of creating a crystal with dimensions higher than that of conventional 3D crystals is an important conceptual breakthrough in physics and it is very exciting for us to be the first to devise a way to realize a space-time crystal.”

Just as a 3D crystal is configured at the lowest quantum energy state when continuous spatial symmetry is broken into discrete symmetry, so too is symmetry breaking expected to configure the temporal component of the space-time crystal. Under the scheme devised by Zhang and Li and their colleagues, a spatial ring of trapped ions in persistent rotation will periodically reproduce itself in time, forming a temporal analog of an ordinary spatial crystal. With a periodic structure in both space and time, the result is a space-time crystal.

“While a space-time crystal looks like a perpetual motion machine and may seem implausible at first glance,” Li says, “keep in mind that a superconductor or even a normal metal ring can support persistent electron currents in its quantum ground state under the right conditions. Of course, electrons in a metal lack spatial order and therefore can’t be used to make a space-time crystal.”

Li is quick to point out that their proposed space-time crystal is not a perpetual motion machine because being at the lowest quantum energy state, there is no energy output. However, there are a great many scientific studies for which a space-time crystal would be invaluable.

“The space-time crystal would be a many-body system in and of itself,” Li says. “As such, it could provide us with a new way to explore classic many-body questions physics questions. For example, how does a space-time crystal emerge? How does time translation symmetry break? What are the quasi-particles in space-time crystals? What are the effects of defects on space-time crystals? Studying such questions will significantly advance our understanding of nature.”

Peng Zhang, another co-author and member of Zhang’s research group, notes that a space-time crystal might also be used to store and transfer quantum information across different rotational states in both space and time. Space-time crystals may also find analogues in other physical systems beyond trapped ions.

“These analogs could open doors to fundamentally new technologies and devices for variety of applications,” he says.

Xiang Zhang believes that it might even be possible now to make a space-time crystal using their scheme and state of the art ion traps. He and his group are actively seeking collaborators with the proper ion-trapping facilities and expertise.

“The main challenge will be to cool an ion ring to its ground state,” Xiang Zhang says. “This can be overcome in the near future with the development of ion trap technologies. As there has never been a space-time crystal before, most of its properties will be unknown and we will have to study them. Such studies should deepen our understandings of phase transitions and symmetry breaking.”

This research was supported primarily by Miller Professorship and Ernest S. Kuh endowed Chair at UC Berkeley, and the National Science Foundations’ Nanoscale Science and Engineering Center.