Altering stem cells to make growth factors needed for replacement tissue inside the body

February 21, 2014

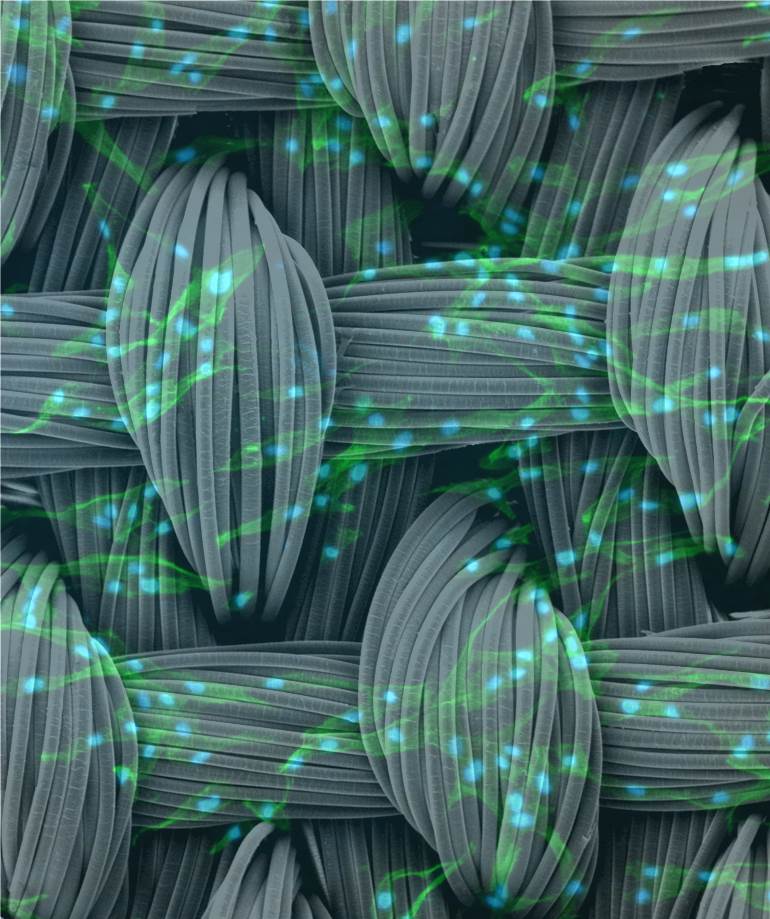

An artistic rendering of human stem cells on polymer scaffolds (credit: Charles Gersbach and Farshid Guilak, Duke University)

By combining a synthetic scaffolding material with gene delivery techniques to direct stem cells into becoming new cartilage, Duke University researchers are getting closer to being able to generate replacement cartilage where it’s needed in the body.

Performing tissue repair with stem cells typically requires applying copious amounts of growth factor proteins — a task that is very expensive and becomes challenging once the developing material is implanted within a body.

In a new study, however, Duke researchers found a way around this limitation by genetically altering the stem cells to make the necessary growth factors all on their own.

They incorporated viruses used to deliver gene therapy to the stem cells into a synthetic material that serves as a template for tissue growth. The resulting material is like a computer: the scaffold provides the hardware and the virus provides the software that programs the stem cells to produce the desired tissue.

The study appears online the week of Feb. 17 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Farshid Guilak, director of orthopaedic research at Duke University Medical Center, has spent years developing biodegradable synthetic scaffolding that mimics the mechanical properties of cartilage. One challenge he and all biomedical researchers face is getting stem cells to form cartilage within and around the scaffolding, especially after it is implanted into a living being.

The traditional approach has been to introduce growth factor proteins, which signal the stem cells to differentiate into cartilage. Once the process is under way, the growing cartilage can be implanted where needed.

“But a major limitation in engineering tissue replacements has been the difficulty in delivering growth factors to the stem cells once they are implanted in the body,” said Guilak, who is also a professor in Duke’s Department of Biomedical Engineering. “There’s a limited amount of growth factor that you can put into the scaffolding, and once it’s released, it’s all gone. We need a method for long-term delivery of growth factors, and that’s where the gene therapy comes in.”

Biomaterial-mediated gene delivery

For ideas on how to solve this problem, Guilak turned to his colleague Charles Gersbach, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and an expert in gene therapy. Gersbach proposed introducing new genes into the stem cells so that they produce the necessary growth factors themselves.

But the conventional methods for gene therapy are complex and difficult to translate into a strategy that would be feasible as a commercial product.

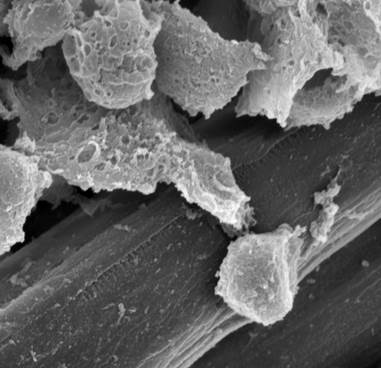

A microscopic view using electron microscopy of human stem cells and viral gene carriers adhering to the fibers of a polymer scaffold (credit: Charles Gersbach and Farshid Guilak, Duke University)

This type of gene therapy generally requires gathering stem cells, modifying them with a virus that transfers the new genes, culturing the resulting genetically altered stem cells until they reach a critical mass, applying them to the synthetic cartilage scaffolding and, finally, implanting it into the body.

“There are a few challenges with that process, one of them being that there are way too many extra steps,” said Gersbach. “So we turned to a technique I had previously developed that affixes the viruses that deliver the new genes onto a material’s surface.”

The new study uses Gersbach’s technique — dubbed biomaterial-mediated gene delivery — to induce the stem cells placed on Guilak’s synthetic cartilage scaffolding to produce growth factor proteins.

The results show that the technique works and that the resulting composite material is at least as good biochemically and biomechanically as if the growth factors were introduced in the laboratory.

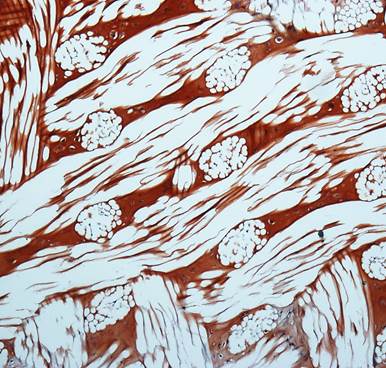

“We want the new cartilage to form in and around the synthetic scaffold at a rate that can match or exceed the scaffold’s degradation,” said Jonathan Brunger, a graduate student who has spent time in both Guilak’s and Gersbach’s laboratories developing and testing the new technique. “So while the stem cells are making new tissue (in the body), the scaffold can withstand the load of the joint. In the ideal case, one would eventually end up with a viable cartilage tissue substitute replacing the synthetic material.”

A cross-section of the engineered tissue showing cartilage (red) filling in between and around the bundles of polymer fibers (white) (credit: Charles Gersbach and Farshid Guilak, Duke University)

Many types of tissues

While this study focuses on cartilage regeneration, Guilak and Gersbach say that the technique could be applied to many kinds of tissues, especially orthopaedic tissues such as tendons, ligaments and bones. And because the platform comes ready to use with any stem cell, it presents an important step toward commercialization.

“One of the advantages of our method is getting rid of the growth factor delivery, which is expensive and unstable, and replacing it with scaffolding functionalized with the viral gene carrier,” said Gersbach. “The virus-laden scaffolding could be mass-produced and just sitting in a clinic ready to go. We hope this gets us one step closer to a translatable product.”

This work was supported in part by the Nancy Taylor Foundation for Chronic Diseases, the Arthritis Foundation, the AO Foundation, the National Science Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.

Abstract of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences paper

The ability to develop tissue constructs with matrix composition and biomechanical properties that promote rapid tissue repair or regeneration remains an enduring challenge in musculoskeletal engineering. Current approaches require extensive cell manipulation ex vivo, using exogenous growth factors to drive tissue-specific differentiation, matrix accumulation, and mechanical properties, thus limiting their potential clinical utility. The ability to induce and maintain differentiation of stem cells in situ could bypass these steps and enhance the success of engineering approaches for tissue regeneration. The goal of this study was to generate a self-contained bioactive scaffold capable of mediating stem cell differentiation and formation of a cartilaginous extracellular matrix (ECM) using a lentivirus-based method. We first showed that poly-l-lysine could immobilize lentivirus to poly(ε-caprolactone) films and facilitate human mesenchymal stem cell (hMSC) transduction. We then demonstrated that scaffold-mediated gene delivery of transforming growth factor β3 (TGF-β3), using a 3D woven poly(ε-caprolactone) scaffold, induced robust cartilaginous ECM formation by hMSCs. Chondrogenesis induced by scaffold-mediated gene delivery was as effective as traditional differentiation protocols involving medium supplementation with TGF-β3, as assessed by gene expression, biochemical, and biomechanical analyses. Using lentiviral vectors immobilized on a biomechanically functional scaffold, we have developed a system to achieve sustained transgene expression and ECM formation by hMSCs. This method opens new avenues in the development of bioactive implants that circumvent the need for ex vivo tissue generation by enabling the long-term goal of in situ tissue engineering.