Brainless slime mold uses external spatial ‘memory’ to navigate complex environments

October 9, 2012

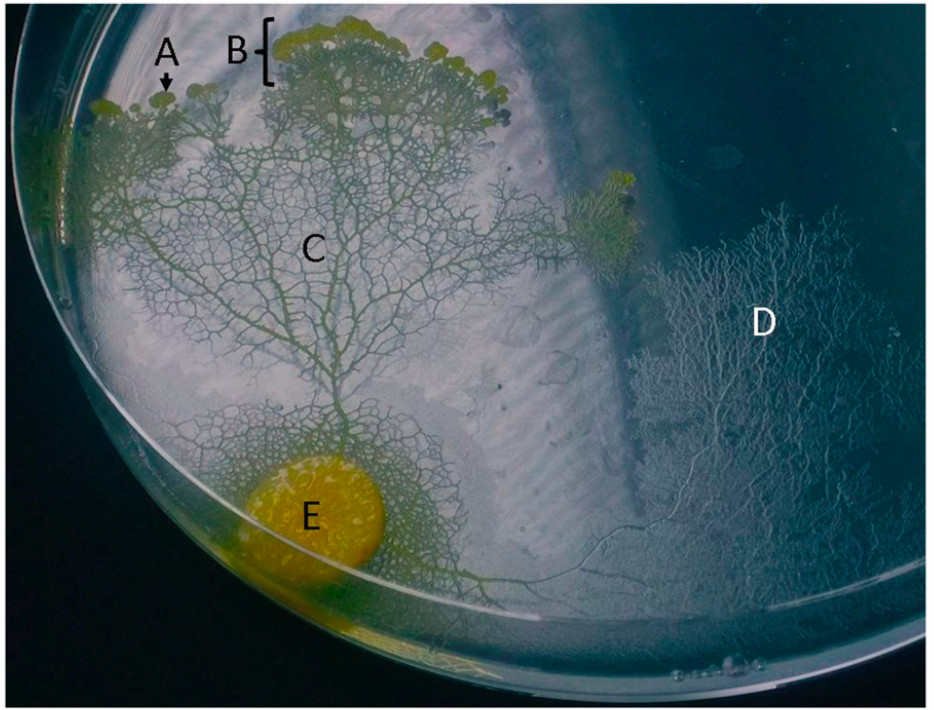

Photograph of P. polycephalum plasmodium showing (A) extending pseudopod, (B) search front, (C) tubule network, and (D) extracellular slime deposited where the cell has previously explored. The food disk containing the inoculation of plasmodial culture is depicted at (E). (Credit: Chris R. Reid et al./PNAS)

They only have a single cell — no brain, but slime molds “remember” where they’ve been.

How? The brainless slime mold Physarum polycephalum constructs a form of spatial “memory” by avoiding areas it has previously explored, researchers at University of Sydney and Université Toulouse III have discovered.

“As it moves, the plasmodium leaves behind a thick mat of nonliving, translucent, extracellular slime,” the scientists said in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, October 8.

“As the plasmodium is foraging, we found. that it strongly avoids areas that contain extracellular slime. This avoidance behavior is a ‘choice’ because when no previously unexplored territory is available, the slime mold no longer avoids extracellular slime.”

The finding is strong support for the theory that the first step toward the evolution of memory was the use of feedback from chemicals.

How to navigate a complex environment without a brain

“We have shown for the first time that a single-celled organism with no brain uses an external spatial memory to navigate through a complex environment,” said Christopher Reid from the University’s School of Biological Sciences.

“Our discovery is evidence of how the memory of multi-cellular organisms may have evolved — by using external chemical trails in the environment before the development of internal memory systems,” said Reid.

“Results from insect studies, for example ants leaving pheromone trails, have already challenged the assumption that navigation requires learning or a sophisticated spatial awareness. We’ve now gone one better and shown that even an organism without a nervous system can navigate a complex environment, with the help of externalized memory.”

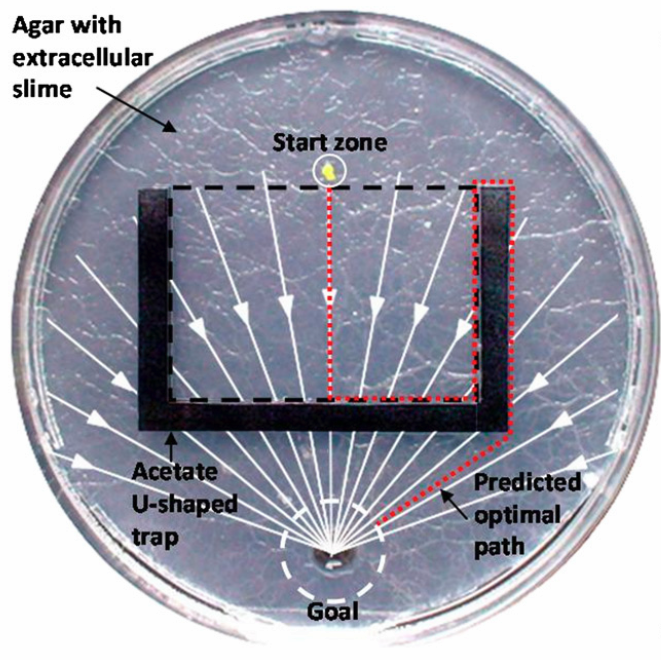

Setup for the U-shaped trap navigational task. The red dashed line shows the predicted optimal path. (Credit: Chris R. Reid et al./PNAS)

The research method was inspired by robots designed to respond only to feedback from their immediate environment to navigate obstacles and avoid becoming trapped. This “reactive navigation” method allows robots to navigate without a programmed map or the ability to build one and slime molds use the same process.

The researchers used a classic test of independent navigational ability, commonly used in robotics, requiring the slime mold to navigate its way out of a U-shaped barrier.

When it is foraging, the slime mold avoids areas that it has already “slimed,” suggesting it can sense extracellular slime upon contact and will recognize and avoid areas it has already explored.

“This shows it is using a form of external spatial memory to more efficiently explore its environment,” said Reid.

“We then upped the ante for the slime mulds by challenging them with the U-shaped trap problem to test their navigational ability in a more complex situation than foraging. We found that, as we had predicted, its success was greatly dependent on being able to apply its external spatial memory to navigate its way out of the trap.”

In simple environments the use of externalized spatial memory is not necessary for effective navigation but in more complex situations it significantly enhances the organism’s chance of success, just as it does for robots using reactive navigation.

No support was found for the rumor that Ghostbusters were involved in the research. — Ed.