Citizen science enters a new era

May 7, 2012 | Source: BBC Future

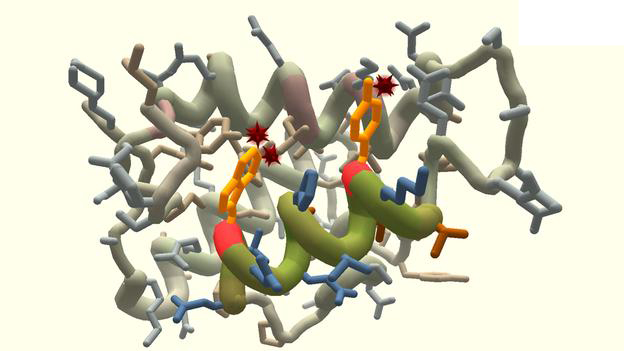

Games like FoldIt allow science problems to be solved through puzzles. Here, players design new proteins, and outperform the best protein-folding algorithms. (Credit: FoldIt)

A new wave of volunteer science projects aims to allow amateur participants to actively gather data for the benefit of their communities.

What has changed is a growing sense that participants can actively take part in projects, rather than passively allowing their idle computer to do the grunt work.

Their feeling is that science is too important to be left to scientists alone,” says Francois Grey from the Citizen Cyberscience Centre, a collaboration set up in 2009 between CERN, the University of Geneva, and the United Nations, with seed money from the Shuttleworth Foundation.

Grey’s Citizen Cyberscience Centre is one of the main operations pushing citizen science into unexplored territories. One reason Grey says this is becoming increasingly possible is that the technology barrier is dropping, so more and more sophisticated hardware can be placed in citizen’s hands.

One project the CCC supports — the “Quake Catcher Network”, or QCN as it is known — epitomizes the trend towards ever-smaller, more nimble devices, based upon the latest chips. A customized external motion-detecting device with a USB plug turns peoples’ ordinary desktops into automated earthquake detectors. Connect computers via the internet to a centralized system, or server, and you now have a wide-ranging system that maps an earthquake’s aftermath.

And soon there could be an army of mobile “quake-catchers”, according to QCN’s Carl Christensen. Smartphones are ideal for the task, as they already have built-in motion-detectors, gyroscopes, accelerometers, and GPS signaling. By summer 2012 QCN expects to release an app that turns your Android smartphone into a pocket-sized earthquake sensor. Soon after, they hope to send 1,000 sensor-equipped phones to places where a fault-line has just slipped.

Some of the hardware being adopted in other citizen science projects also hail from unexpected origins. A major advance in scientific computing came from the development of superfast 3D Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) to run video games on Sony’s PlayStation 3 console. GPUs can do 10 times more than an ordinary chip. Consequently, Dave Anderson, founder of the open-source software platform BOINC, foresees volunteer computing at an “exascale” level – about 1,000,000,000,000,000,000 calculations per second – 100 times more powerful than today’s top supercomputers.

But the deepest forests of the Congo Basin may provide a glimpse of where citizen science could be heading. An initiative aims to help pygmy tribes fight logging and poaching in this area by allowing them to document destruction and deforestation with games and interactive maps.

This initiative is part of the Extreme Citizen Science program based at University College London. The idea is to allow any community, regardless of their literacy to start, run, and analyse a scientific study, whether it is to advance interests, or to effect policy change.

They are working with indigenous people in the Republic of Congo and Cameroon to develop data collection tools that can be used by non-literate people. In the 1990s, vast regions of forest in the Congo Basin were divided up and sold to multinational companies to mine resources. But by the mid-2000s, many of these companies wanted FSC (Forest Stewardship Council) certification to signify products that are from responsibly harvested and verified sources, and they turned to people like Lewis for help.

So they devised ways for monitoring what the indigenous people wanted to preserve, for instance, trees from which they harvest a particularly delicious and tradable species of caterpillar. People are equipped with touchscreen devices with icons for various options like “valuable tree” that they can select and tag with GPS coordinates.