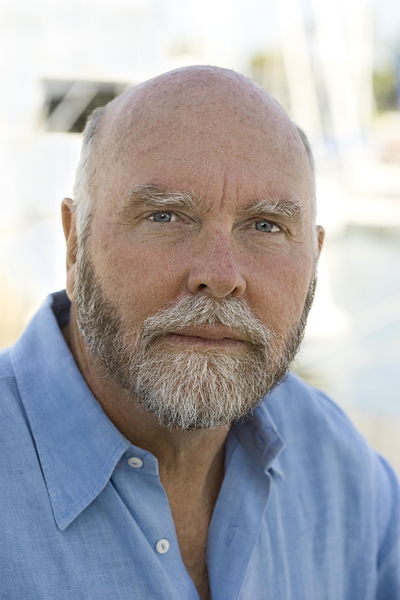

Craig Venter’s bugs might save the world

May 31, 2012 | Source: New York Times

Inside the laboratories of biotechnology, a literal possibility of artificial life is taking hold: What if machines really were alive?

The possibility of designing a new organism, entirely from synthetic DNA, to produce whatever compounds we want, would mark a radical leap forward in biotechnology and a paradigm shift in manufacturing.

The appeal of biological machinery is manifold:

- Because organisms reproduce, they can generate not only their target product but also more factories to do the same.

- A custom organism could produce the same plastic or metal as an industrial plant while feeding on the compounds in pollution or the energy of the sun.

- As the world population continues to soar, adding nearly a billion people over the past decade, major aquifers are giving out, and agriculture may not be able to keep pace with the world’s needs. If a strain of algae could secrete high yields of protein, using less land and water than traditional crops, it may represent the best hope to feed a booming planet.

- The rise of biomachinery could usher in an era of “distributed manufacturing” by microbes. For example, customers could simply synthesize the bugs at home and grow them on their skin: “Living perfume”

In 2003, Venter’s lab used a new method to piece together a strip of DNA that was identical to a natural virus, then watched it spring to action and attack a cell. In 2008, they built a longer genome, replicating the DNA of a whole bacterium, and in 2010 they announced that they brought a bacterium with synthetic DNA to life.

In theory, this leaves just one step between Venter and a custom species. If he can change its genetic function in some deliberate way, he will have crossed the threshold to designer life.

If the promise of synthetic biology is expansive, the potential for catastrophe is plain. The greater the reach of biomachinery, the more urgent the need to understand its risks. Looking to the dawn of a biomachine age, many environmental groups worry that synthetic bugs could become the ultimate invasive species.

The reassurance offered by Venter and other proponents may not be convincing to everyone. A synthetic bug, they say, has little chance of surviving in the competitive natural ecosystem, and anyway, it could be designed to die without chemical support. In 2010, President Obama ordered his bioethics commission to examine the implications of Venter’s work, and the commission found “limited risks.”

“We’re doing a grand experiment. We’re trying to design the first cell from scratch.”

The synthetic biology that Venter proposes, using a minimal genome as a platform to make advances in food, fuel, medicine and environmental health, could backfire into a biological calamity, but it could also offer the most transformative approach to a medley of problems with no apparent solution.

Venter said he was just days away from trying the first synthesis of a minimal genome. “I call it the Hail Mary Genome.”