Crowdsourcing the psych lab

September 4, 2012

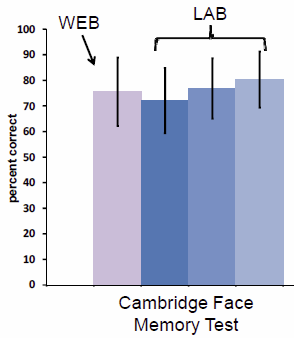

Web vs. lab data for variability across multiple samples. Bars show + or – 1 standard deviation. (Credit: Laura Germine et al.)

Can we trust data from anonymous, unpaid volunteers on the Web as a source of data for psychology experiments? Yes, according to new research conducted by Harvard scientists

By conducting experiments online, researchers have been able to enlist as many as 65,000 volunteers to take part in studies of cognition, a number far larger than they could bring into the lab.

Despite the cost and time advantages, researchers continue to worry that data from Web volunteers will not be as good as data from paid lab participants, said Laura Germine, a postdoctoral research associate in Harvard’s Psychology Department.

To test whether Web studies are as valid as those done in the lab, researchers recruited thousands of volunteers through TestMyBrain.org, a website run by Germine. Navigating via search engines and social networking sites, the volunteers took part in a handful of tests to learn more about themselves and contribute to scientific research.

These tests were designed to assess everything from facial recognition ability to a person’s capacity for remembering a long string of numbers. Researchers then compared the results of the online tests with those done in the lab.

“We looked at three basic metrics,” Germine explained. “We looked at mean performance, we looked at variation in performance, and we looked at internal consistency. On each measure, Germine said, the results from studies conducted with Web volunteers were the same as those done in the lab.

“We’ve shown that data from self-selected Web volunteers can be very good. It’s fast, it’s cheap, but it’s not dirty. In experiments like ours, what you’re getting is good, reliable data.”

Insights from online communities

By forming communities online, Germine said, people who suffer from a particular disorder have been able to raise awareness — and drive research in areas that might otherwise not be studied.

“The other benefit that comes from using the Web is that people can offer insights about themselves we might not think to ask,” Germine said. “The best example of this is with the selective developmental disorders.”

Arguably the most prominent example of such a disorder is prosopagnosia, also known as “face blindness,” in which individuals have difficulty recognizing people, sometimes even in their own families. Although the condition was occasionally reported following a stroke, when people claimed to have had the disorder from birth, they were often dismissed by doctors and researchers. As tests for facial recognition were made available online, researchers began to realize that the disorder was far more common than previously thought.

“As a result, we learned a great deal,” Germine said. “Because we had these tests available online, and because people were able to participate in this exploration online, the knowledge they gained validated their own experience, which encouraged them to get in contact with a researcher. So there was this circle of knowledge that became very beneficial to everyone involved.

“The Web offers us another avenue to take advantage of that, and to engage people in our science in a new way. I think there’s a great opportunity for collaboration between scientists and ‘citizen scientists’ to advance scientific knowledge.”

So what psych experiments would you like to see done online?