Earth’s massive extinction 250 million years ago caused by mercury

January 6, 2012

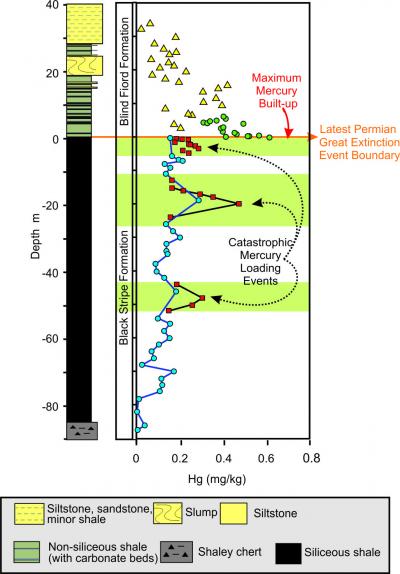

This graphic shows historical variations of Mercury (Hg) deposition before and after the Latest Permian Extinction event as recorded in a sedimentary section in the High Arctic, Canada. The vertical axis demonstrates the depth of the sedimentary section relative to the extinction boundary while the horizontal looks at the amount of mercury accumulation (concentration in the rock) as measured in milligram per kilogram. (Credit: Hamed Sanei, Steve Grasby and Benoit Beauchamp)

Scientists have discovered a a new culprit likely involved in Earth’s greatest extinction event 250 million years ago (when rapid climate change wiped out nearly all marine species and a majority of those on land): an influx of mercury into the ecosystem.

“This was a time of the greatest volcanic activity in Earth’s history and we know today that the largest source of mercury comes from volcanic eruptions,” says Dr. Steve Grasby, a research scientist at Natural Resources Canada and an adjunct professor at the University of Calgary.

“We estimate that the mercury released then could have been up to 30 times greater than today’s volcanic activity, making the event truly catastrophic.”

Dr. Benoit Beauchamp, professor of geology at the University of Calgary, says this study is significant because it’s the first time mercury has been linked to the cause of the massive extinction that took place during the end of the Permian, about 250 million years ago.

During the period, the natural buffering system in the ocean became overloaded with mercury, contributing to the loss of 95 per cent of life in the sea.

The mercury deposition rates could have been significantly higher in the late Permian when compared with today’s human-caused emissions. In some cases, levels of mercury in the late Permian ocean were similar to what is found near highly contaminated ponds near smelters, where the aquatic system is severely damaged, say researchers.

“We are adding to the levels through industrial emissions. This is a warning for us here on Earth today,” adds Beauchamp. In North America, at least, there has been a steady decline through regulations controlling mercury.

The generally accepted idea has been that volcanic eruptions burned though coal beds, releasing CO2 and other deadly toxins. Direct proof of this theory was outlined in a paper that was published by these same authors last January in Nature Geoscience.

No matter what happens, this study shows life’s tenacity. “The story is one of recovery as well. After the system was overloaded and most of life was destroyed, the oceans were still able to self clean and we were able to move on to the next phase of life,” says lead author Hamed Sanei, research scientist at Natural Resources Canada and adjunct professor at the University of Calgary.

Ref.: Hamed Sanei, Stephen E. Grasby, and Benoit Beauchamp, Latest Permian mercury anomalies, Geology, 2011 [doi: 10.1130/G32596.1]