First transistors made entirely of nanocrystal ‘inks’ in simplified process

April 8, 2016

Because this process works at relatively low temperatures, many transistors can be made on a flexible backing at once. (credit: University of Pennsylvania)

University of Pennsylvania engineers have developed a simplified new approach for making transistors by sequentially depositing their components in the form of liquid nanocrystal “inks.” The new process open the door for transistors and other electronic components to be built into flexible or wearable applications. It also avoids the highly complex current process for creating transistors, which requires high-temperature, high-vacuum equipment. Also, the new lower-temperature process is compatible with a wide array of materials and can be applied to larger areas.

Transistors patterned on plastic backing

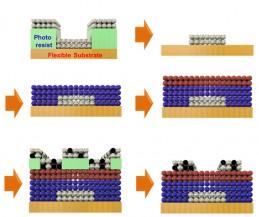

The researchers’ nanocrystal-based field effect transistors were patterned onto flexible plastic backings using spin coating, but could eventually be constructed by additive manufacturing systems, like 3D printers.

Published in the journal Science, the study was lead by Cherie Kagan, the Stephen J. Angello Professor in the School of Engineering and Applied Science, and Ji-Hyuk Choi, then a member of her lab, now a senior researcher at the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources. Researchers at Korea University Korea’s Yonsei University were also involved.

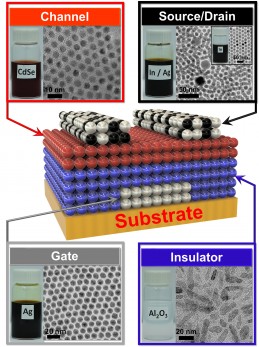

Kagan’s group developed four nanocrystal inks that comprise the transistor, then deposited them on a flexible backing. (credit: University of Pennsylvania)

The researchers began by dispersing a specific type of nanocrystals in a liquid, creating nanocrystal inks. They developed a library of four of these inks: a conductor (silver), an insulator (aluminum oxide), a semiconductor (cadmium selenide), and a conductor combined with a dopant (a mixture of silver and indium). (“Doping” the semiconductor layer of a transistor with impurities controls whether the device creates a positive or negative charge.)

“These materials are colloids just like the ink in your inkjet printer,” Kagan said, “but you can get all the characteristics that you want and expect from the analogous bulk materials, such as whether they’re conductors, semiconductors or insulators.” Although the electrical properties of several of these nanocrystal inks had been independently verified, they had never been combined into full devices. “Our question was whether you could lay them down on a surface in such a way that they work together to form functional transistors.”

Laying down patterns in layers

Such a process entails layering or mixing them in precise patterns.

First, the conductive silver nanocrystal ink was deposited from liquid on a flexible plastic surface that was treated with a photolithographic mask, then rapidly spun to draw it out in an even layer. The mask was then removed to leave the silver ink in the shape of the transistor’s gate electrode.

The researchers followed that layer by spin-coating a layer of the aluminum oxide nanocrystal-based insulator, then a layer of the cadmium selenide nanocrystal-based semiconductor and finally another masked layer for the indium/silver mixture, which forms the transistor’s source and drain electrodes. Upon heating at relatively low temperatures, the indium dopant diffused from those electrodes into the semiconductor component.

“The trick with working with solution-based materials is making sure that, when you add the second layer, it doesn’t wash off the first, and so on,” Kagan said. “We had to treat the surfaces of the nanocrystals, both when they’re first in solution and after they’re deposited, to make sure they have the right electrical properties and that they stick together in the configuration we want.”

Because this entirely ink-based fabrication process works at lower temperatures than existing vacuum-based methods, the researchers were able to make several transistors on the same flexible plastic backing at the same time.

The inks’ specialized surface chemistry allowed them to stay in configuration without losing their electrical properties. (credit: University of Pennsylvania)

“Making transistors over larger areas and at lower temperatures have been goals for an emerging class of technologies, when people think of the Internet of things, large area flexible electronics and wearable devices,” Kagan said. “We haven’t developed all of the necessary aspects so they could be printed yet, but because these materials are all solution-based, it demonstrates the promise of this materials class and sets the stage for additive manufacturing.”

Because this entirely ink-based fabrication process works at lower temperatures than existing vacuum-based methods, the researchers were able to make several transistors on the same flexible plastic backing at the same time.

3D-printing transistors for wearables

“This is the first work,” Choi said, “showing that all the components, the metallic, insulating, and semiconducting layers of the transistors, and even the doping of the semiconductor, could be made from nanocrystals.”

“Making transistors over larger areas and at lower temperatures have been goals for an emerging class of technologies, when people think of the Internet of things, large area flexible electronics and wearable devices,” Kagan said. “We haven’t developed all of the necessary aspects so they could be printed yet, but because these materials are all solution-based, it demonstrates the promise of this materials class and sets the stage for additive manufacturing.”

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the U.S. Department of Energy, the Office of Naval Research, and the Korea Institute of Geoscience and Mineral Resources funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning of Korea.

Abstract of Exploiting the colloidal nanocrystal library to construct electronic devices

Synthetic methods produce libraries of colloidal nanocrystals with tunable physical properties by tailoring the nanocrystal size, shape, and composition. Here, we exploit colloidal nanocrystal diversity and design the materials, interfaces, and processes to construct all-nanocrystal electronic devices using solution-based processes. Metallic silver and semiconducting cadmium selenide nanocrystals are deposited to form high-conductivity and high-mobility thin-film electrodes and channel layers of field-effect transistors. Insulating aluminum oxide nanocrystals are assembled layer by layer with polyelectrolytes to form high–dielectric constant gate insulator layers for low-voltage device operation. Metallic indium nanocrystals are codispersed with silver nanocrystals to integrate an indium supply in the deposited electrodes that serves to passivate and dope the cadmium selenide nanocrystal channel layer. We fabricate all-nanocrystal field-effect transistors on flexible plastics with electron mobilities of 21.7 square centimeters per volt-second.