How cancer cells form tumors by reaching out with ‘cables’ and grabbing cells

January 27, 2016

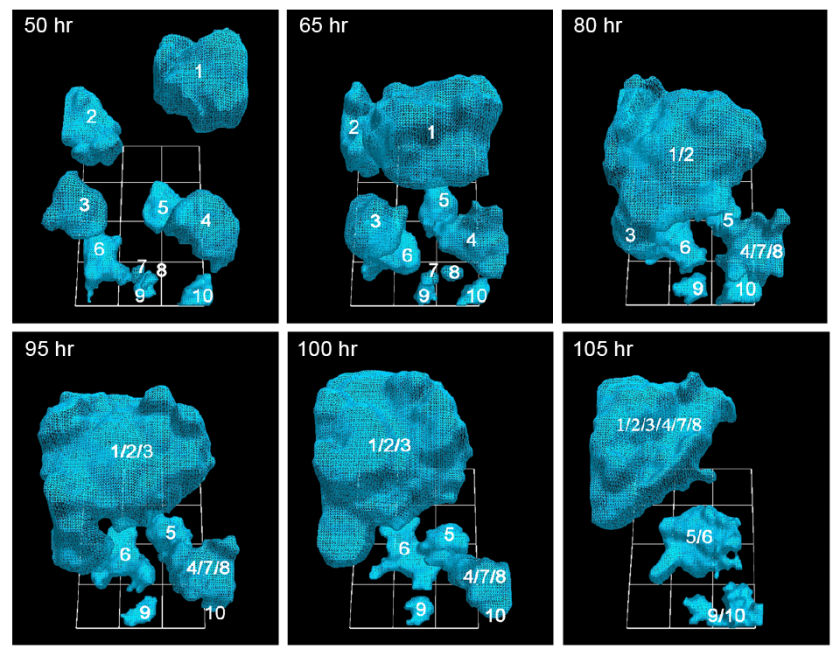

University of Iowa | Cancer cells’ motion and accretion into tumors

Two University of Iowa studies have recorded the movements of cancerous human breast tissue cells in real time and in 3D — the first time cancer cells’ motion and accretion into tumors has been continuously tracked, the researchers believe.

The team discovered that cancerous cells, moving at move at 92 micrometers per hour (about twice the speed of healthy cells), actively recruit healthy cells into tumors by extending a kind of cable to grab their neighbors — both cancerous and healthy — and reel them in. Surprisingly, as little as five percent of cancerous cells are needed to form the tumors, a ratio previously unknown.

“It’s not like things sticking to each other,” said David Soll, biology professor at the UI and corresponding author on the open-access paper, published in the American Journal of Cancer Research. “It’s that these cells go out and actively recruit. It’s complicated stuff, and it’s not passive. No one had a clue that there were specialized cells in this process, and that it’s a small number that pulls all the rest in.”

The findings could lead to a more precise identification of tumorigenic cells (those that form tumors) and to testing which antibodies would be best equipped to eliminate them.*

How cancer cells “know” what to do

The question is: how do these cells know what to do. Soll hypothesizes they’re reaching back to a primitive past, when these cells were programmed to form embryos. If true, perhaps the cancerous cells — masquerading as embryo-forming cells — recruit other cells to make tissue that then forms the layered, self-sustaining architecture needed for a tumor to form and thrive. “It’s as if it’s building its own defenses against the body’s efforts to defeat them.”

University of Iowa researchers have documented how cancerous tumors form by tracking in real time the movement of individual cells in 3-D. They report that just 5 percent of cancer cells are needed to form tumors, a ratio that heretofore had been unknown. (credit: Soll Laboratory)

In the AJCR paper, the researchers found support for their previous observation that tumorigenic cell lines and fresh tumor cells possess the unique capacity to form tumors by the active formation of cellular cables.

The finding lends more weight to the idea that tumors are created concurrently, in multiple locations, by individual clusters of cells that employ the cancer-cell cables to draw in more cells and enlarge themselves. Some have argued that tumors come about more by cellular changes within the masses, known as the “cancer stem cell theory.”

The Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank funded the study.

* Soll’s Monoclonal Antibody Research Institute and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, created by the National Institutes of Health as a national resource, directed by Soll and housed at the UI, together contain one of the world’s largest collections of antibodies that could be used for the anti-cancer testing, based on the new findings.

Abstract of Mediated coalescence: a possible mechanism for tumor cellular heterogeneity

Recently, we demonstrated that tumorigenic cell lines and fresh tumor cells seeded in a 3D Matrigel model, first grow as clonal islands (primary aggregates), then coalesce through the formation and contraction of cellular cables. Non-tumorigenic cell lines and cells from normal tissue form clonal islands, but do not form cables or coalesce. Here we show that as little as 5% tumorigenic cells will actively mediate coalescence between primary aggregates of majority non-tumorigenic or non-cancerous cells, by forming cellular cables between them. We suggest that this newly discovered, specialized characteristic of tumorigenic cells may explain, at least in part, why tumors contain primarily non-tumorigenic cells.