How cancer chromosome abnormalities form in living cells

August 12, 2013

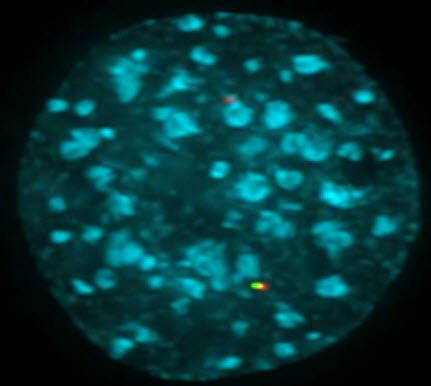

A chromosome translocation with breaks visualized by differently colored fluorescent proteins (green, red). DNA is stained cyan. (Credit: NCI)

National Cancer Institute (NCI) scientists have directly observed events that lead to the formation of a chromosome abnormality that is often found in cancer cells.

The abnormality, called a translocation, occurs when part of a chromosome breaks off and becomes attached to another chromosome.

Chromosomes are thread-like structures inside cells that carry genes and function in heredity. Human chromosomes each contain a single piece of DNA, with the genes arranged in a linear fashion along the length of the DNA.

Chromosome translocations have been found in almost all cancer cells, and it has long been known that translocations can play a role in cancer development. However, despite many years of research, just exactly how translocations form in a cell has remained a mystery.

To better understand this process, the researchers created an experimental system in which they induced, in a controlled fashion, breaks in the DNA of different chromosomes in living cells. Using sophisticated imaging technology, they were then able to watch as the broken ends of the chromosomes were reattached correctly or incorrectly inside the cells.

Translocations are very rare events, and the scientists’ ability to visualize their occurrence in real time was made possible by recently available technology at NCI that enables investigators to observe changes in thousands of cells over long time periods.

The scientists were able to demonstrate that translocations can occur within hours of DNA breaks and that their formation is independent of when the breaks happen during the cell division cycle. Cells have built-in repair mechanisms that can fix most DNA breaks, but translocations occasionally occur.

To explore the role of DNA repair in translocation formation, the researchers inhibited key components of the DNA damage response machinery within cells and monitored the effects on the repair of DNA breaks and translocation formation.

They found that inhibition of one component of DNA damage response machinery, a protein called DNAPK-kinase, increased the occurrence of translocations almost 10-fold. The scientists also determined that translocations formed preferentially between pre-positioned genes.

“These observations have allowed us to formulate a time and space framework for elucidating the mechanisms involved in the formation of chromosome translocations,” said Vassilis Roukos, Ph.D., NCI, lead scientist of the study.

“We can now finally begin to really probe how these fundamental features of cancer cells form,” Misteli added.

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NCI’s Center for Cancer Research.