How neurons make sense of our senses

November 22, 2011

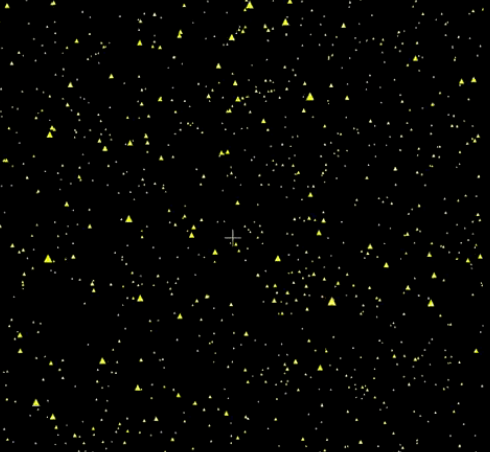

Moving straight ahead (credit: University of Rochester)

Scientists at the University of Rochester, Washington University in St. Louis, and Baylor College of Medicine have unraveled how the brain manages to process the complex, rapidly changing, and often conflicting sensory signals to make sense of our world.

The answer lies in a simple computation performed by single nerve cells: a weighted average. Neurons have to apply the correct weights to each sensory cue, and the authors reveal how this is done.

The discovery may eventually lead to new therapies for people with Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders that impair a person’s sense of self-motion, says study coauthor Greg DeAngelis, professor and chair of brain and cognitive sciences at the University of Rochester.

This deeper understanding of how brain circuits combine different sensory cues could also help scientists and engineers to design more sophisticated artificial nervous systems such as those used in robots, he adds.

The study shows that the brain does not have to first “decide” which sensory cue is more reliable. The study demonstrates that the low-level computations performed by single neurons in the brain, when repeated by millions of neurons performing similar computations, accounts for the brain’s complex ability to know which sensory signals to weight as more important. “Thus, the brain essentially can break down a seemingly high-level behavioral task into a set of much simpler operations performed simultaneously by many neurons,” explains DeAngelis.

The study confirms and extends a computational theory developed earlier by brain and cognitive scientist Alexandre Pouget at the University of Rochester and the University of Geneva, and a coauthor on the paper. The theory predicted that neurons fire in a manner predicted by a weighted summation rule, which was largely confirmed by the neural data. However, the weights that the neurons learned were slightly off target from the theoretical predictions, and the difference could explain why behavior also varies slightly from subject to subject, the authors conclude. “Being able to predict these small discrepancies establishes an exciting connection between computations performed at the level of single neurons and detailed aspects of behavior,” says DeAngelis.

To gather the data, the researchers designed a virtual-reality system to present subjects with two directional cues: a visual pattern of moving dots on a computer screen to simulate traveling forward and physical movement of the subject created by a platform. The researchers varied the amount of randomness in the motion of the dots to change how reliable the visual cues were relative to the motion of the platform. At the end of each trial, subjects indicated which direction they were heading, to the right or to the left.

Ref.: Christopher R Fetsch, et al., Neural correlates of reliability-based cue weighting during multisensory integration, Nature Neuroscience, 20 November 2011; [DOI:10.1038/nn.2983]