How to catch a derelict satellite

February 21, 2014

A future ESA mission called e.DeOrbit plans to capture derelict satellites adrift in orbit, part of ESA’s Clean Space initiative — an effort to control space debris to reduce the environmental impact of the space industry on Earth and space alike.

Risks of space junk

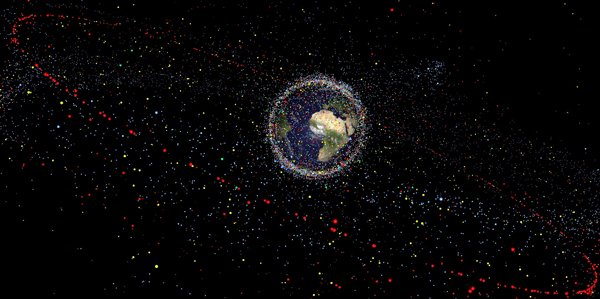

Distribution of debris: all human-made space objects result from the near-5000 launches since the start of the space age. About 65% of the catalogued objects, however, originate from break-ups in orbit – more than 240 explosions – as well as fewer than 10 known collisions. Scientists estimate the total number of space debris objects in orbit to be around 29 000 for sizes larger than 10 cm, 670 000 larger than 1 cm, and more than 170 million larger than 1 mm. (Click twice for full-size image) (Credit: ESA)

Decades of launches have left Earth surrounded by a halo of space junk: more than 17 000 trackable objects larger than a coffee cup, which threaten working missions with catastrophic collision. Even a 1 cm nut could hit with the force of a hand grenade.

Such uncontrolled multi-ton items are not only collision risks but also time bombs: they risk exploding due to leftover fuel or partially charged batteries heated up by orbital sunlight. The resulting debris clouds would make these vital orbits much more hazardous and expensive to use, and follow-on collisions may eventually trigger a chain reaction of breakups.

The only way to control the debris population across key low orbits is to remove large items such as derelict satellites and launcher upper stages.

Targeting key orbits

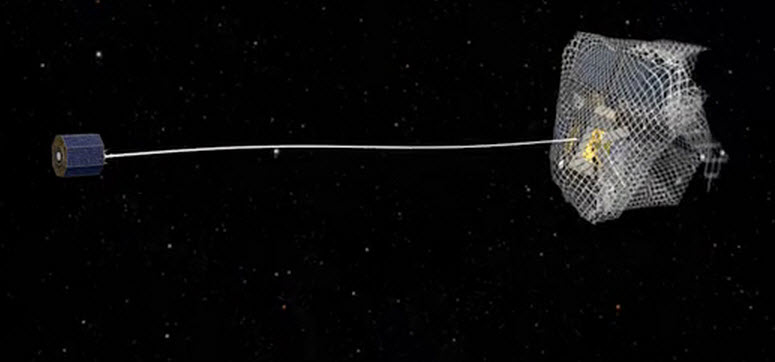

Space debris removal mission: simulations of orbital debris show that actively removing large items of debris, such as entire derelict satellites, should help stabilise its population and prevent a collision-based cascade effect. ESA has performed a system study for an Active Debris Removal mission called e.Deorbit. (Credit: ESA)

e.DeOrbit is designed to target debris items in well-trafficked polar orbits, between 800 km to 1000 km altitude. At around 1600 kg, e.DeOrbit will be launched on ESA’s Vega rocket.

The first technical challenge the mission will face is to capture a massive, drifting object left in an uncertain state, which may well be tumbling rapidly. Sophisticated imaging sensors and advanced autonomous control will be essential, first to assess its condition and then approach it.

Making rendezvous and then steady stationkeeping with the target is hard enough but then comes the really difficult part: how to secure it safely ahead of steering the combined satellite and salvage craft down for a controlled burn-up in the atmosphere?

Several capture mechanisms are being studied in parallel to minimize mission risk. Throw-nets have the advantage of scalability — a large enough net can capture anything, no matter its size and attitude. Tentacles, a clamping mechanism that builds on current berthing and docking mechanisms, could allow the capture of launch adapter rings of various different satellites.

Harpoons work no matter the target’s attitude and shape, and do not require close operations. Robotic arms are another option: results from the DLR German space agency’s forthcoming DEOS orbital servicing mission will be studied with interest.

Strong drivers for the platform design are not only the large amount of propellant required, but also the possible rapid tumbling of the target – only so much spin can be absorbed without the catcher craft itself going out of control.

Apart from deorbit options based on flexible and rigid connections, techniques are being considered for raising targets to higher orbits, including tethers and electric propulsion.

A symposium on May 6 in the Netherlands will cover studies and technology developments related to e.DeOrbit, with ESA and space industry representatives presenting their research and outlining their plans. For further information, or to register, go here.