How to connect your home appliances to the Internet of Things

November 13, 2012

(Credit: Sigfox)

French startup SigFox thinks it can help usher in a second mobile Internet boom by connecting millions of low-power sensors worldwide to the Internet, MIT Technology Review reports.

SigFox is focused on connecting cheap sensors and “dumb” home appliances to the Internet. The goal is to make all kinds of appliances and infrastructure, from power grids to microwave ovens, smarter by letting them share data. The general concept, known as “the Internet of Things,” has been discussed in academic circles for years, but it has yet to come to life.

SigFox builds its networks in the same way as a cellular provider, using a system of connected antennas that each cover a particular area and link back to the operator’s central network. But the antennas use a different radio technology, developed by SigFox, known as ultra narrow band. This technology would not be of much use for streaming video to an iPhone, but it allows devices connecting to the network to consume very little energy, says Thomas Nicholls, chief of business development and Internet of Things evangelism at SigFox, and it allows for very long-range connections.

SigFox claims that a conventional cellular connection consumes 5,000 microwatts, but a two-way SigFox connection uses just 100. The company also says it is close to rolling out a network to the whole of France using just 1,000 antennas. Deployments are beginning in other European countries, and discussions are under way with U.S.-based cellular carriers about teaming up to roll out its technology stateside, says Nicholls.

Further cost savings come from operating the technology on parts of the radio spectrum that are free to use. SigFox expects to offer its service to a connected device for as little as $1 a year.

The features that make SigFox’s network cheap to install and maintain have the downside of limiting the network’s speed. At best, it can currently transfer information at the rate of 100 bits per second,

The smart grid connection

SigFox reports seeing most interest in its technology from companies trying to roll out so-called smart grids, an approach to electricity distribution that uses data from sensors throughout a power network — including in customers’ homes — to help improve efficiency and reliability.

“We have clients that want to connect with water pipes underground, or monitor parking spaces to detect occupancy and power billing — they just can’t do that with GSM,” Nicholls says. A smart parking lot system based on SigFox’s network is coming soon in a “large European country,” he says, and a project in central Africa will use a SigFox network to monitor endangered animals at risk from poachers.

The technology could also find use in home medical devices and gadgets. To save battery life, gadgets don’t keep a Wi-Fi connection active at all times, which can mean waiting a few seconds for a connection to be reestablished before using the device. A device with a SigFox connection could send data instantly, says Nicholls, without any Wi-Fi configuration or network.

Ready to connect unencrypted data from your home appliances to the world?

It’s not clear if SigFox’s connection to the nebulous “Internet of Things” means there might be a connection to the standard Internet (or even if unintended by SigFox).

If so, there are some issues. Researchers at the University of South Carolina have discovered that some types of electricity meters connected via smart grids are broadcasting unencrypted information that, with the right software, would enable eavesdroppers to determine whether you’re at home,” warns Computerworld.

The meters, called AMR (automatic meter reading) in the utility industry, are a first-generation smart meter technology and they are installed in one third of American homes and businesses. They are intended to make it easy for utilities to collect meter readings. Instead of requiring access to your home, workers need simply drive or walk by a house with a handheld terminal and the current meter reading can be received.

There’s also no evidence to suggest that burglars have ever used AMR meters as a way of predicting when a home owner will be present or away, but the research does highlight the potential nefarious uses of electricity consumption data and the need to ensure next-generation platforms are more secure, Computerworld points out — if that’s even possible.

It’s not clear if SigFox has thought this one through. Connecting an electrical utility’s smart grid to the Internet could expand access to hackers and government spooks worldwide, tying into the residents’ social networks, which already provide way too much information that allows clever criminals to piece together where you live and your comings and goings.

The connection could possibly even give terrorists a new tool for taking down a power grid.

Does the word Stuxnet ring a bell?

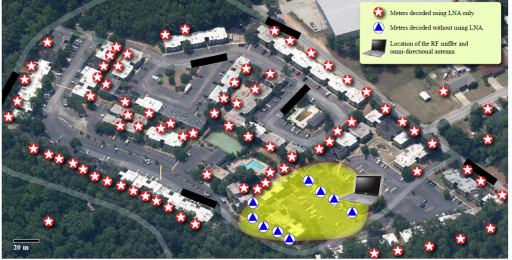

An aerial view of the neighborhood where University of South Carolina engineers performed eavesdropping experiments. Each blue triangle or red star represents a group of four or five meters mounted in a cluster on an exterior wall. Using an LNA and a 5 dBi omnidirectional antenna, they were able to monitor all meters in the neighborhood. (Credit: Ishtiaq Rouf et al.)