How to erase fear from your brain

September 24, 2012

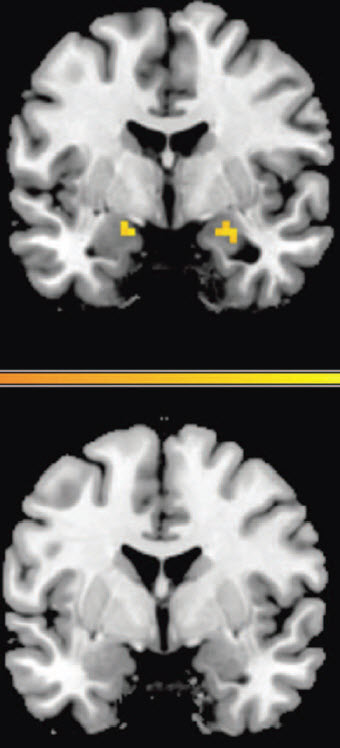

Amygdala activity predicts return of fear and correlates with recall of fear. Without disruption of reconsolidation (top), fear (yellow) returned. With disruption (bottom), fear did not return. (Credit: T. Agren, J. Engman, A. Frick, J. Bjorkstrand, E.-M. Larsson, T. Furmark, M. Fredrikson/Science)

Newly formed emotional memories can be erased from the human brain, Uppsala University researchers have shown.

When a person learns something, a lasting long-term memory is created with the aid of a process of consolidation, which is based on the formation of proteins. When we remember something, the memory becomes unstable for a while and is then restabilized by another consolidation process.

In other words, we are not remembering what originally happened, but rather what we remembered the last time we thought about what happened. By disrupting the reconsolidation process that follows upon remembering, we can affect the content of memory.

(This is related to a recent Northwestern University finding that a memory is modified during recall (see Why your memory is like the telephone game).

The study

The researchers showed subjects a neutral picture and simultaneously administered an electric shock, creating a fear memory. To activate this fear memory, the picture was then shown without any accompanying shock.

For one experimental group the reconsolidation process was disrupted with the aid of repeated presentations of the picture (“extinction training”) within the “reconsolidation window” (10 minutes).

For a control group, the reconsolidation process was allowed to complete by waiting six hours before the subjects were shown the same repeated presentations of the picture.

So by disrupting the reconsolidation process, the memory was rendered neutral and no longer incited fear. Using a fMRI scanner, the researchers were able to show that the traces of that memory also disappeared from the part of the brain that normally stores fearful memories: the nuclear group of amygdala in the temporal lobe.

‘These findings may be a breakthrough in research on memory and fear. Ultimately, the new findings may lead to improved treatment methods for the millions of people in the world who suffer from anxiety issues like phobias, post-traumatic stress, and panic attacks,” says Thomas Ågren, a doctoral candidate at the Department of Psychology and co-author of the study.