How touch and movement neurons shape the brain’s internal image of the body

September 10, 2013

The avatar arm evoking the rubber hand illusion in a monkey (credit: Duke University)

The brain’s tactile and motor neurons, which perceive touch and control movement, may also respond to visual cues, according to researchers at Duke Medicine.

The phenomenon has some similarity to the “McGurk effect,” where visual cues dominate sound.

The study in monkeys provides new information on how different areas of the brain may work together in continuously shaping the brain’s internal image of the body, also known as the body schema.

The findings have implications for paralyzed individuals using neuroprosthetic limbs, since they suggest that the brain may assimilate neuroprostheses as part of the patient’s own body image.

“The study shows for the first time that the somatosensory or touch cortex may be influenced by vision, which goes against everything written in neuroscience textbooks,” said senior author Miguel Nicolelis, M.D., PhD, professor of neurobiology at Duke University School of Medicine.

“The findings support our theory that the cortex isn’t strictly segregated into areas dealing with one function alone, like touch or vision.”

The rubber hand illusion and virtual touch

Earlier research has shown that the brain has an internal spatial image of the body, which is continuously updated based on touch, pain, temperature and pressure — known as the somatosensory system — received from skin, joints and muscles, as well as from visual and auditory signals.

An example of this dynamic process is the “rubber hand illusion,” a phenomenon in which people develop a sense of ownership of a fake hand when they view it being touched at the same time that something touches their own hand.

In an effort to find a physiological explanation for the “rubber hand illusion,” Duke researchers focused on brain activity in the somatosensory and motor cortices of monkeys. These two areas of the brain do not directly receive visual input, but previous work in rats, conducted at the Edmond and Lily Safra International Institute of Neuroscience of Natal in Brazil, theorized that the somatosensory cortex could respond to visual cues.

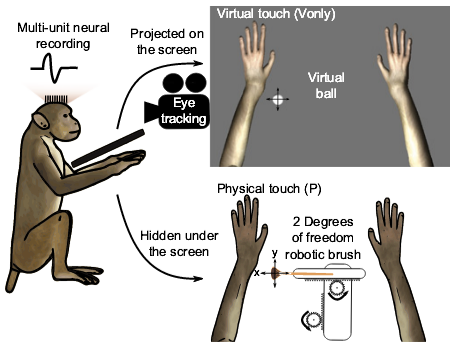

The monkey’s arms were restrained underneath a computer screen. Three-dimensional arms were shown on the screen, with the size and position approximating the arms. Physical touches were applied with a brush mounted on a robot. (Credit: Solaiman Shoku et al./PNAS)

In the Duke experiment, the two monkeys observed a realistic, computer-generated image of a monkey arm on a screen being touched by a virtual ball. At the same time, the monkeys’ arms were touched, triggering a response in their somatosensory and motor cortical areas.

The monkeys then observed the ball touching the virtual

arm without anything physically touching their own arms. Within a matter of minutes, the researchers saw the neurons located in the somatosensory and motor cortical areas begin to respond to the virtual arm alone being touched.

The responses to virtual touch occurred 50 to 70 milliseconds later than physical touch, which is consistent with the timing involved in the pathways linking the areas of the brain responsible for processing visual input to the somatosensory and motor cortices. Demonstrating that somatosensory and motor cortical neurons can respond to visual stimuli suggests that cross-functional processing occurs throughout the primate cortex through a highly distributed and dynamic process.

“These findings support our notion that the brain works like a grid or network that is continuously interacting,” Nicolelis said. “The cortical areas of the brain are processing multiple streams of information at the same time instead of being segregated as we previously thought.”

Implications for design of neuroprosthetic devices

The research has implications for the future design of neuroprosthetic devices controlled by brain-machine interfaces, which hold promise for restoring motor and somatosensory function to millions of people who suffer from severe levels of body paralysis. Creating neuroprostheses that become fully incorporated in the brain’s sensory and motor circuitry could allow the devices to be integrated into the brain’s internal image of the body.

Wearable robot (exoskeleton) (credit: Walk Again Project)

Nicolelis said he is incorporating the findings into the Walk Again Project, an international collaboration working to build a brain-controlled neuroprosthetic device. The Walk Again Project plans to demonstrate its first brain-controlled exoskeleton during the opening ceremony of the 2014 FIFA Football World Cup.

The project’s central goal is to develop and implement the first BMI capable of restoring full mobility to patients suffering from a severe degree of paralysis. This lofty goal will be achieved by building a neuroprosthetic device that uses a BMI as its core, allowing the patients to capture and use their own voluntary brain activity to control the movements of a full-body prosthetic device.

This “wearable robot,” also known as an “exoskeleton,” will be designed to sustain and carry the patient’s body according to his or her mental will.

“As we become proficient in using tools — a violin, tennis racquet, computer mouse, or prosthetic limb – our brain is likely changing its internal image of our bodies to incorporate the tools as extensions of ourselves,” Nicolelis said.

In additional to Nicolelis, other study authors include Solaiman Shokur and Hannes Bleuler of the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland; Joseph E. O’Doherty of the Department of Biomedical Engineering and Center for Neuroengineering at Duke University; Jesse Winans of the Department of Biomedical Engineering at Duke University; and Mikhail A. Lebedev of the Center for Neuroengineering and Department of Neurobiology at Duke University School of Medicine.

The research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (DP1MH099903), National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS073952) and École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL-IMT-LSRO1 Grant 1016-1).