Human stem cells created by cloning

May 16, 2013

(Credit: Masahito Tachibana et al./Cell)

It was hailed some 15 years ago as the great hope for a biomedical revolution: production of patient-specific embryonic stem cells (ESCs) from cloning to create perfectly matched tissues that would someday cure ailments ranging from diabetes to Parkinson’s disease.

Since then, the approach has been enveloped in ethical debate. A paper published by Shoukhrat Mitalipov, a reproductive biology specialist at the Oregon Health and Science University in Beaverton, and his colleagues is sure to rekindle that debate, Nature News reports.

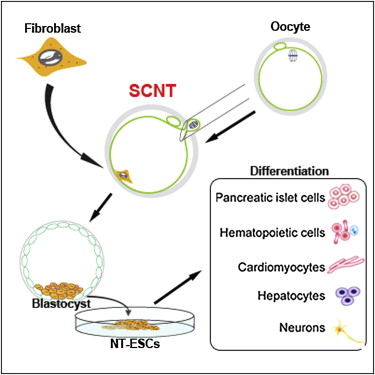

Therapeutic cloning, or somatic-cell nuclear transfer (SCNT), begins with the same process used to create Dolly, the famous cloned sheep, in 1996.

A donor cell from a body tissue such as skin is fused with an unfertilized egg from which the nucleus has been removed. The egg ‘reprograms’ the DNA in the donor cell to an embryonic state and divides until it has reached the early, blastocyst stage. The cells are then harvested and cultured to create a stable cell line that is genetically matched to the donor and that can become almost any cell type in the human body.

Mitalipov and his group began work on their new study last September, using eggs from young donors recruited through a university advertising campaign. In December, after some false starts, cells from four cloned embryos that Mitalipov had engineered began to grow. “It looks like colonies, it looks like colonies,” he kept thinking. Masahito Tachibana, a fertility specialist from Sendai, Japan, who is finishing a 5-year stint in Mitalipov’s laboratory, nervously sectioned the 1-millimetre-wide clumps of cells and transferred them to new culture plates, where they continued to grow — evidence of success. Mitalipov cancelled his holiday plans. “I was happy to spend Christmas culturing cells,” he says. “My family understood.”

The success came through minor technical tweaks. The researchers used inactivated Sendai virus (known to induce fusion of cells) to unite the egg and body cells, and an electric jolt to activate embryo development. When their first attempts produced six blastocysts but no stable cell lines, they added caffeine, which protects the egg from premature activation.

None of these techniques is new, but the researchers tested them in various combinations in more than 1,000 monkey eggs before moving on to human cells.

Public fears that the technology might be used to create human clones are a sticking point. The research might spark “cloning hysteria” that opponents of stem-cell research could capitalize on, says Bernard Siegel, executive director of the Genetics Policy Institute in Palm Beach, Florida.