Immune cells in covering of brain discovered; may play critical role in battling neurological diseases

December 28, 2016

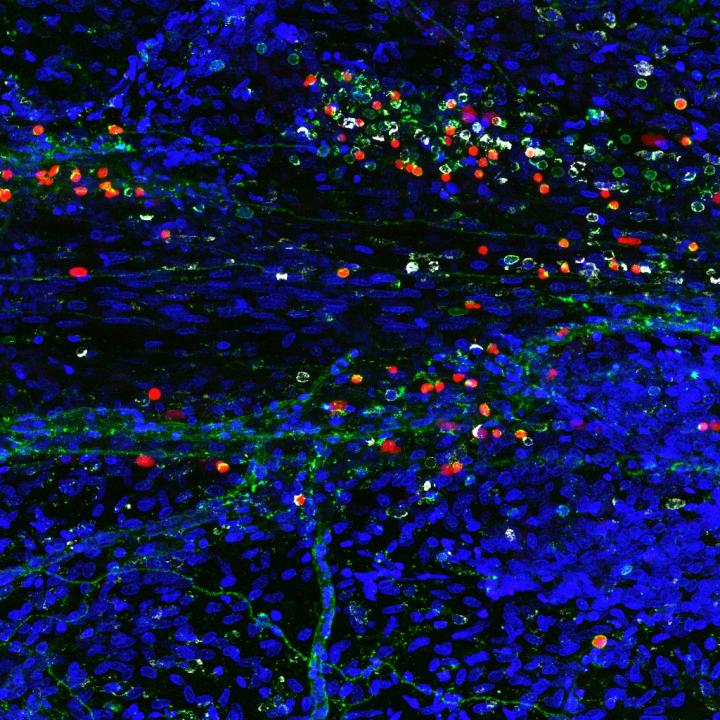

A composite image showing newly discovered immune cells in the brain (credit: Sachin Gadani | University of Virginia School of Medicine)

University of Virginia School of Medicine researchers have discovered a rare and powerful type of immune cell in the meninges (protective covering) of the brain that are activated in response to central nervous system injury — suggesting that these cells may play a critical role in battling Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis, meningitis, and other neurological diseases, and in supporting healthy mental functioning.

By harnessing the power of the cells, known as “type 2 innate lymphocytes” (ILC2s), doctors may be able to develop new treatments for neurological diseases, traumatic brain injury, and spinal cord injuries, as well as migraines, the researchers suggest. They also suspect the cells may be the missing link connecting the brain and the microbiota in our guts, a relationship that has been shown to be important in the development of Parkinson’s disease.

Important immune roles

ILC2 cells have previously been found in the gut, lung, and skin, the body’s barriers to disease. Their discovery by UVA researcher Jonathan Kipnis, PhD, in the meninges, the membranes surrounding the brain, comes as a surprise. They were found along the same vessels discovered by the Kipnis lab last year, which showed that the brain and the immune system are directly connected.

“This all comes down to immune system and brain interaction,” said Kipnis, chairman of UVA’s Department of Neuroscience. These where previously believed to be not communicating, but not only are these [immune] cells present in the areas near the brain, they are integral to its function, Kipnis said.

Immune cells play several important roles within the body, including guarding against pathogens, triggering allergic reactions, and responding to spinal cord injuries. But its their role in the gut that makes Kipnis suspect they may also be serving as a vital communicator between the brain’s immune response and our microbiomes (microbes in the body). That could be very important, because our intestinal flora is critical for maintaining our health and well being.

“These cells are potentially the mediator between the gut and the brain. They are the main responder to microbiota changes in the gut,” Kipnis said. “They may go from the gut to the brain, or they may just produce something that will impact those cells. We know the brain responds to things happening in the gut. Is it logical that these will be the cells that connect the two? Potentially.”

The findings have been published online by the Journal of Experimental Medicine. The work was supported by a National Institutes of Health grant.

Abstract of Characterization of meningeal type 2 innate lymphocytes and their response to CNS injury

The meningeal space is occupied by a diverse repertoire of immune cells. Central nervous system (CNS) injury elicits a rapid immune response that affects neuronal survival and recovery, but the role of meningeal inflammation remains poorly understood. Here, we describe type 2 innate lymphocytes (ILC2s) as a novel cell type resident in the healthy meninges that are activated after CNS injury. ILC2s are present throughout the naive mouse meninges, though are concentrated around the dural sinuses, and have a unique transcriptional profile. After spinal cord injury (SCI), meningeal ILC2s are activated in an IL-33–dependent manner, producing type 2 cytokines. Using RNAseq, we characterized the gene programs that underlie the ILC2 activation state. Finally, addition of wild-type lung-derived ILC2s into the meningeal space of IL-33R−/− animals partially improves recovery after SCI. These data characterize ILC2s as a novel meningeal cell type that responds to SCI and could lead to new therapeutic insights for neuroinflammatory conditions.