Implanted user interfaces

May 7, 2012

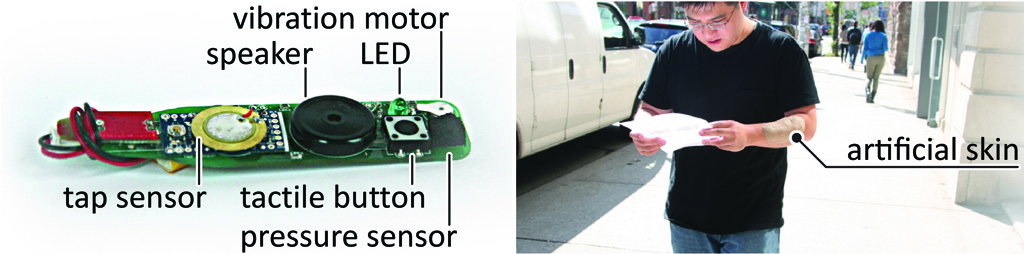

A prototype device (a) was covered with a layer of artificial skin (b) for use in an outdoor scenario (credit: Autodesk Research)

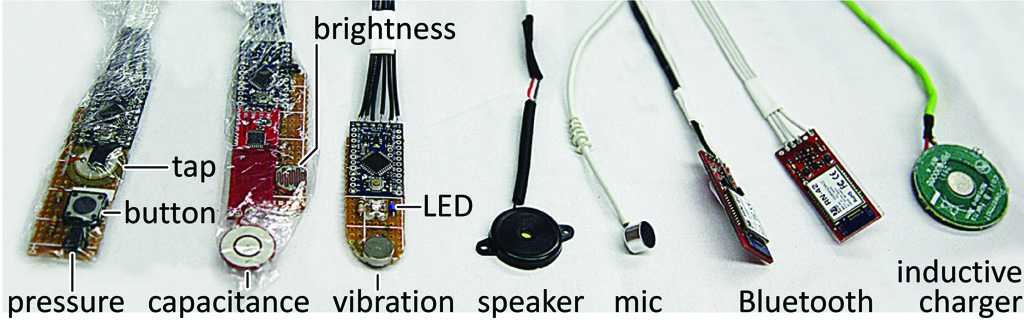

Scientists at Autodesk Research and their colleagues have tested a dozen or so different user interface implants, Txchnologist reports. Input devices included microphones for audio; buttons, pressure sensors and tap sensors for input via direct touching of the skin; and brightness sensors and capacitive sensors — the kind now often found in mobile device touchscreens — for input through motions above the skin. Output devices they examined included audio speakers, LEDs, and vibration motors. Wireless communications were enabled using Bluetooth, and wireless recharging was tested with inductive chargers, the kind seen with cordless power tools.

To see how well these devices might operate under the skin, researchers implanted them in an arm from a lightly embalmed cadaver, between the skin and the underlying fatty tissue. They also developed artificial patches of skin made from silicone that people could wear on their forearms and walk around with — these covered the devices, simulating implantation.

These devices were implanted in a cadaver during the study. Plastic bags around devices prevented contact with tissue fluid (credit: Autodesk Research)

“We showed these can all still operate through the skin,” said Autodesk researcher Tovi Grossman. “These results open up a lot of possibilities.”

The scientists will present their work Monday May 7 at the CHI conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in Austin, Texas.

Such implanted user interfaces could wirelessly communicate with devices such as the augmented reality eyewear Google is developing with Project Glass, Grossman said. These implants could also help people control other devices within their bodies. “Medical implants already exist, but there are no real ways to easily get the status of these devices, or use them to get information about the state of your health, or be able to control the doses of various drugs,” he added.

Implanted user interfaces could also be used to control items around the house like remote controls, or to play games, suggested human-computer interaction researcher Albrecht Schmidt at the University of Stuttgart in Germany, who did not take part in this study. “You can also extend social networks into your body — be connected with others with implants, feel pulses of vibration from others,” he added. “This can get very personal… it’s a way of letting someone under your skin.”

Simple, more passive implants might also include memory cards, “so that you never have to worry about bringing important files with you to a meeting or the office — you have data with you at all times, under the skin,” Grossman said. A notification system involving blinking lights or a little buzz on the arm could also alert users to appointments or messages, and implanted watches could help people always tell the time. Schmidt added that motion-sensing accelerometers could also analyze how you move your body, for gesture control of devices or for keeping track of how active you are when it comes to monitoring fitness.

One concern about such implanted devices would be security — any device that can be accessed wirelessly should have protection in place against unwanted intruders, the researchers said.

The conveniences provided by such implants raises the question of whether they might become pervasive. “We might see a situation similar to mobile phones — if they provide a direct benefit, then there’s pressure for everyone to get it,” Schmidt said. “Ten years ago, it was quite optional to have a phone or not, but now for people who live a regular life in society, it’s not really an option anymore.”

Ref.: Christian Holz, Tovi Grossman, George Fitzmaurice, and Anne Agur, Implanted User Interfaces, CHI 2012 Conference Proceedings, ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2012, In Press