Infrared-light-based Wi-Fi network is 100 times faster

March 22, 2017

Schematic of a beam of white light being dispersed by a prism into different wavelengths, similar in prinicple to how a new near-infrared WiFi system works (credit: Lucas V. Barbosa/CC)

A new infrared-light WiFi network can provide more than 40 gigabits per second (Gbps) for each user* — about 100 times faster than current WiFi systems — say researchers at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e) in the Netherlands.

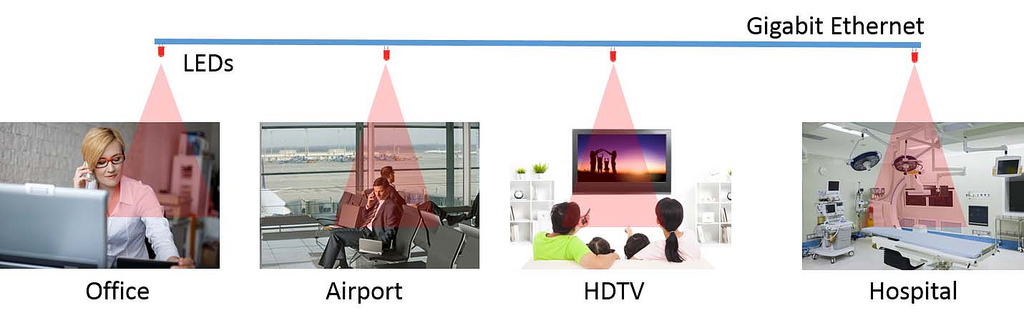

The TU/e WiFi design was inspired by experimental systems using ceiling LED lights (such as Oregon State University’s experimental WiFiFO, or WiFi Free space Optic, system), which can increase the total per-user speed of WiFi systems and extend the range to multiple rooms, while avoiding interference from neighboring WiFi systems. (However, WiFiFo is limited to 100 Mbps.)

Experimental Oregon State University system uses LED lighting to boost the bandwidth of Wi-Fi systems and extend range (credit: Thinh Nguyen/Oregon State University)

Near-infrared light

Instead of visible light, the TU/e system uses invisible near-infrared light.** Supplied by a fiber optic cable, a few central “light antennas” (mounted on the ceiling, for instance) each use a pair of “passive diffraction gratings” that radiate light rays of different wavelengths at different angles.

That allows for directing the light beams to specific users. The network tracks the precise location of every wireless device, using a radio signal transmitted in the return direction.***

The TU/e system uses infrared light with a wavelength of 1500 nanometers (a frequency of 200 terahertz, or 40,000 times higher than 5GHz), allowing for significantly increased capacity. The system has so far used the light rays only for downloading; uploads are still done using WiFi radio signals, since much less capacity is usually needed for uploading.

The researchers expect it will take five years or more for the new technology to be commercially available. The first devices to be connected will likely be high-data devices like video monitors, laptops, and tablets.

* That speed is 67 times higher than the current 802.11n WiFi system’s max theoretical speed of 600Mbps capacity — which has to be shared between users, so the ratio is actually about 100 times, according to TU/e researchers. That speed is also 16 times higher than the 2.5 Gbps performance with the best (802.11ac) Wi-Fi system — which also has to be shared (so actually lower) — and in addition, uses the 5GHz wireless band, which has limited range. “The theoretical max speed of 802.11ac is eight 160MHz 256-QAM channels, each of which are capable of 866.7Mbps, for a total of 6,933Mbps, or just shy of 7Gbps,” notes Extreme Tech. “In the real world, thanks to channel contention, you probably won’t get more than two or three 160MHz channels, so the max speed comes down to somewhere between 1.7Gbps and 2.5Gbps. Compare this with 802.11n’s max theoretical speed, which is 600Mbps.”

** The TU/e system was designed by Joanne Oh as a doctoral thesis and part of the wider BROWSE project headed up by professor of broadband communication technology Ton Koonen, with funding from the European Research Council, under the auspices of the noted TU/e Institute for Photonic Integration.

*** According to TU/e researchers, a few other groups are investigating network concepts in which infrared-light rays are directed using movable mirrors. The disadvantage here is that this requires active control of the mirrors and therefore energy, and each mirror is only capable of handling one ray of light at a time. The grating used the and Oh can cope with many rays of light and, therefore, devices at the same time.