Living organ regenerated for first time

April 10, 2014

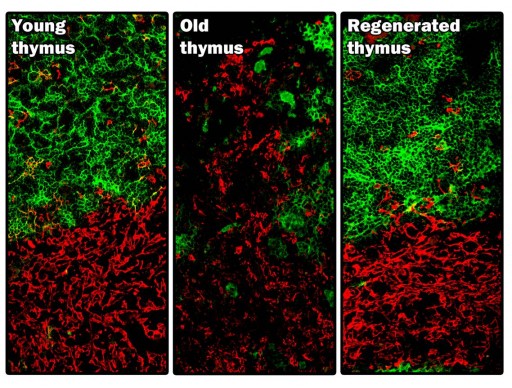

A comparison of the thymus in a young and old mouse, plus one that has had the treatment (credit: N. Bredenkamp et al./MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine, University of Edinburgh)

A team of scientists at the University of Edinburgh has rebuilt the thymus of an old mouse — the first regeneration of a living organ.

After treatment, the regenerated organ had a structure similar to that found in a young mouse.

The thymus is an organ in the body located next to the heart that produces important immune cells. The advance could pave the way for new therapies for people with damaged immune systems and genetic conditions that affect thymus development.

The function of the thymus was also restored and the mice began making more white blood cells called T cells, which are important for fighting off infection. However, it is not yet clear whether the immune system of the mice was improved.

The study was led by researchers from the Medical Research Council Centre for Regenerative Medicine at the University of Edinburgh.

The researchers targeted a protein produced by cells of the thymus called FOXN1, which helps to control how important genes are switched on. By increasing levels of FOXN1, the team instructed stem cell-like cells to rebuild the organ.

Treatment hope

“Our results suggest that targeting the same pathway in humans may improve thymus function and therefore boost immunity in elderly patients, or those with a suppressed immune system. However, before we test this in humans we need to carry out more work to make sure the process can be tightly controlled,” said Clare Blackburn, Professor of Tissue Stem Cell Biology, MRC Centre for Regenerative Medicine.

The thymus deteriorates with age, which is why older people are often more susceptible to infections such as flu. The discovery could also offer hope to patients with DiGeorge syndrome, a genetic condition that causes the thymus to not develop properly.

“One of the key goals in regenerative medicine is harnessing the body’s own repair mechanisms and manipulating these in a controlled way to treat disease,” said Rob Buckle, M.D., Head of Regenerative Medicine, Medical Research Council. “This interesting study suggests that organ regeneration in a mammal can be directed by manipulation of a single protein, which is likely to have broad implications for other areas of regenerative biology.”

The study is published in the journal Development.

Abstract of Development paper

Thymic involution is central to the decline in immune system function that occurs with age. By regenerating the thymus, it may therefore be possible to improve the ability of the aged immune system to respond to novel antigens. Recently, diminished expression of the thymic epithelial cell (TEC)-specific transcription factor Forkhead box N1 (FOXN1) has been implicated as a component of the mechanism regulating age-related involution. The effects of upregulating FOXN1 function in the aged thymus are, however, unknown. Here, we show that forced, TEC-specific upregulation of FOXN1 in the fully involuted thymus of aged mice results in robust thymus regeneration characterized by increased thymopoiesis and increased naive T cell output. We demonstrate that the regenerated organ closely resembles the juvenile thymus in terms of architecture and gene expression profile, and further show that this FOXN1-mediated regeneration stems from an enlarged TEC compartment, rebuilt from progenitor TECs. Collectively, our data establish that upregulation of a single transcription factor can substantially reverse age-related thymic involution, identifying FOXN1 as a specific target for improving thymus function and, thus, immune competence in patients. More widely, they demonstrate that organ regeneration in an aged mammal can be directed by manipulation of a single transcription factor, providing a provocative paradigm that may be of broad impact for regenerative biology.