Major drug company to market implantable microchips that deliver drugs inside the body

July 6, 2015

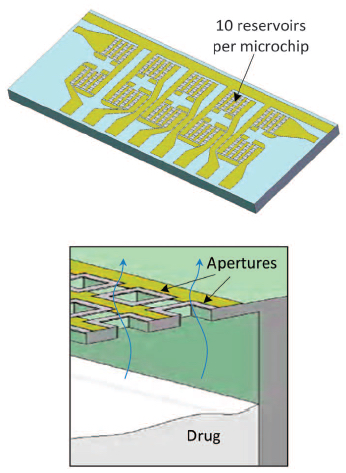

Implantable microchip-based drug delivery device (credit: Robert Farra et al./Science Translational Medicine)

MIT spinoff Microchips Biotech has partnered with Teva Pharmaceutical, the world’s largest producer of generic drugs, to commercialize its wirelessly controlled, implantable, microchip-based devices that store and release drugs inside the body over a period of years.

Invented by Microchips Biotech co-founders Michael Cima, the David H. Koch Professor of Engineering, and Robert Langer, the David H. Koch Institute Professor, the device can be programmed wirelessly to release individual doses for up to 16 years to treat, for example, diabetes, cancer, multiple sclerosis, and osteoporosis.*

Top: 10 reservoirs per microchip. Bottom: cross section of one reservoir showing drug being released. (credit: Robert Farra et al./Science Translational Medicine)

The microchips consist of hundreds of pinhead-sized reservoirs, each capped with a metal membrane, that store tiny doses of therapeutics or chemicals. A programmed electric current delivered by the device removes the reservoir membrane, releasing a single dose.

Microchips Biotech also plans to co-develop microchips to treat specific diseases, and will continue work on its flagship product, a birth-control microchip, backed by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, that releases contraceptives and can be turned on and off wirelessly.

Improving adherence to medication prescriptions

Microchips Biotech says these microchips could also improve medication-prescription adherence. A 2012 report published in the Annals of Internal Medicine estimated that Americans who don’t stick to prescriptions rack up $100 billion to $289 billion annually in unnecessary health care costs from additional hospital visits and other issues. Failure to follow prescriptions, the study also found, causes around 125,000 deaths annually and up to 10 percent of all hospitalizations.

* In 2011, Langer and Cima, and researchers from MicroCHIPS, conducted the microchips’ first human trials to treat osteoporosis — this time with wireless capabilities. In that study, published in a 2012 issue of Science Translational Medicine, microchips were implanted into seven elderly women, delivering teriparatide to strengthen bones. Results indicated that the chips delivered doses comparable to injections — and did so more consistently — with no adverse side effects.

A major innovation was enabling final assembly of the microchips at room temperature with hermetic seals, using a modified cold-welding “tongue and groove” process by depositing a soft, gold alloy in patterns on the top of the chip to create tongues, and grooves on the base. By pressing the top and base pieces together, the tongues fit into the grooves, and plastically deforms to weld the metal together to ensure a seal.