‘Mind-Control’ gaming devices leak users’ secrets

August 22, 2012

A sequence of credit cards is presented to the user. Her brainwaves from an EEG device (EPOC from Emotiv Systems in this case) are monitored by a computer. (Credit: Ivan Martinovic et al)

In a study of 28 subjects wearing brain-machine interface devices built by companies like Neurosky and Emotiv and marketed to consumers for gaming and attention exercises, researchers found they were able to extract hints directly from the electrical signals of the test subjects’ brains that partially revealed private information, like the location of their homes, faces they recognized and even their credit card PINs, Forbes reports.

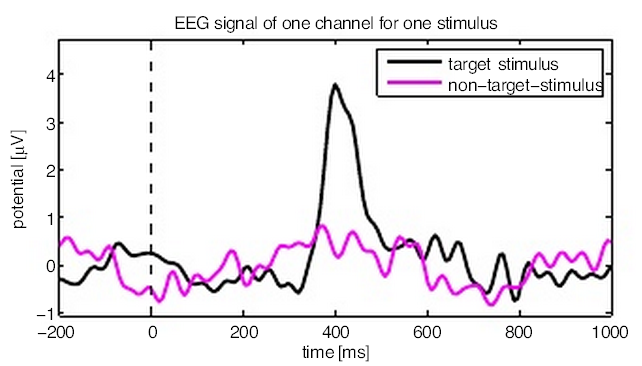

In their experiments, the researchers first showed users wearing the mind-control headsets a series of known images and numbers to measure what a moment of recognition looked like in their EEG data, using the P300 response, a electrical spike that typically appears close to 300 milliseconds after a stimulus the subject recognizes.

Then they showed the subjects a series of test images and numbers and looked for those same signals. In a collection of unknown faces, for instance, they found a significant spike in the EEG data for a picture of Barack Obama that revealed the test subjects’ recognition of the president’s face.

A P300 event-related potential elicited as a brain response to a target stimuli (in this experiment the non-target stimuli were pictures of unknown faces, while the target stimuli was the picture showing President Obama) (credit: Ivan Martinovic et al)

When shown a collection of locations on maps that included one of their home, the headset-wearers’ brains emitted tell-tale hints that allowed the experimenters to determine their home’s general location with 60% accuracy on the first try among a collection of ten choices.

And when the subjects were asked to memorize a four-digit PIN and then shown a series of random numbers, the researchers found they could guess which of those random numbers was the first digit in the PIN with about 30% accuracy on the first try–far from a home run, but a significantly higher success rate than a random guess.