On/off button for passing along epigenetic ‘memories’ to our children discovered

March 29, 2016

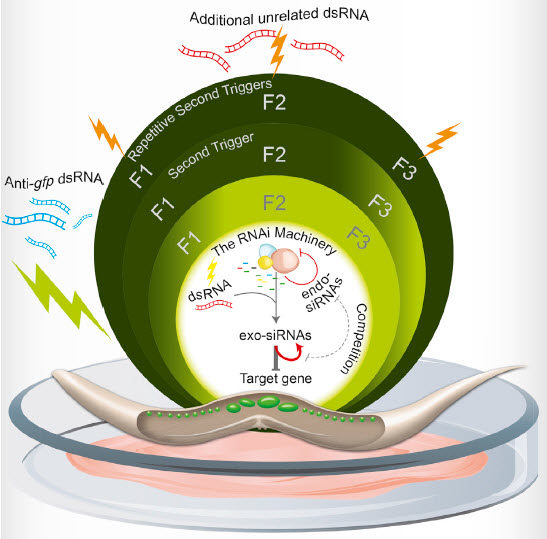

The duration of epigenetic responses underpinning transgenerational inheritance is determined by an active mechanism relying on the production of small RNAs and modulation of RNAi factors, dictating whether ancestral RNAi responses would be memorized or forgotten (credit: Leah Houri-Ze’evi et al./Cell)

According to epigenetics — the study of inheritable changes in gene expression not directly coded in our DNA — our life experiences may be passed on to our children and our children’s children. Studies on survivors of traumatic events have suggested that exposure to stress may indeed have lasting effects on subsequent generations.

But exactly how are these genetic “memories” passed on?

A new Tel Aviv University (TAU ) study published last week in Cell now pinpoints the precise mechanism that turns the inheritance of these environmental influences “on” and “off.”

How specific genes and small RNAs control epigenetic inheritance

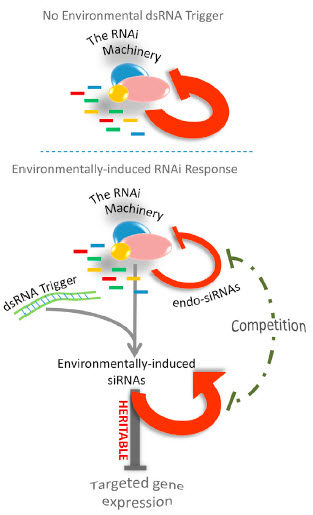

Interactions between different heritable RNAi responses, and the feedback loop that times the duration of transgenerational silencing (credit: Leah Houri-Ze’evi et al./Cell)

“Until now, it has been assumed that a passive dilution or decay governs the inheritance of epigenetic responses,” said Oded Rechavi, PhD, from TAU’s Faculty of Life Sciences and Sagol School of Neuroscience. “But we showed that there is an active process that regulates epigenetic inheritance down through generations.”

The scientists discovered that specific genes, which they named “MOTEK” (Modified Transgenerational Epigenetic Kinetics), were involved in turning epigenetic transmissions on and off.

“We discovered how to manipulate the transgenerational duration of epigenetic inheritance in worms by switching ‘on’ and ‘off’ the small RNAs that worms use to regulate [these] genes,” said Rechavi.*

These switches are controlled by a feedback interaction between gene-regulating small RNAs, which are inheritable, and the MOTEK genes that are required to produce and transmit these small RNAs across generations.

The feedback determines whether epigenetic memory will continue to the progeny or not, and how long each epigenetic response will last.

The researchers are now planning to study the MOTEK genes to know exactly how these genes affect the duration of epigenetic effects, and whether similar mechanisms exist in humans.

* Rechavi and his team had previously identified a “small RNA inheritance” mechanism through which RNA molecules produced a response to the needs of specific cells and how they were regulated between generations.

“We previously showed that worms inherited small RNAs following the starvation and viral infections of their parents. These small RNAs helped prepare their offspring for similar hardships,” Dr. Rechavi said. “We also identified a mechanism that amplified heritable small RNAs across generations, so the response was not diluted. We found that enzymes called RdRPs are required for re-creating new small RNAs to keep the response going in subsequent generations.”

Most inheritable epigenetic responses in C.elegans worms were found to persist for only a few generations. This created the assumption that epigenetic effects simply “petered out” over time, through a process of dilution or decay.

“But this assumption ignored the possibility that this process doesn’t simply die out but is regulated instead,” said Dr. Rechavi, who in this study treated C.elegans worms with small RNAs that target the GFP (green fluorescent protein), a reporter gene commonly used in experiments. “By following heritable small RNAs that regulated GFP — that “silenced” its expression — we revealed an active, tuneable inheritance mechanism that can be turned ‘on’ or ‘off.'”

Abstract of A Tunable Mechanism Determines the Duration of the Transgenerational Small RNA Inheritance in C. elegans

In C. elegans, small RNAs enable transmission of epigenetic responses across multiple generations. While RNAi inheritance mechanisms that enable “memorization” of ancestral responses are being elucidated, the mechanisms that determine the duration of inherited silencing and the ability to forget the inherited epigenetic effects are not known. We now show that exposure to dsRNA activates a feedback loop whereby gene-specific RNAi responses dictate the transgenerational duration of RNAi responses mounted against unrelated genes, elicited separately in previous generations. RNA-sequencing analysis reveals that, aside from silencing of genes with complementary sequences, dsRNA-induced RNAi affects the production of heritable endogenous small RNAs, which regulate the expression of RNAi factors. Manipulating genes in this feedback pathway changes the duration of heritable silencing. Such active control of transgenerational effects could be adaptive, since ancestral responses would be detrimental if the environments of the progeny and the ancestors were different.