Scientists reveal secrets for reaching age 100 (or more)

August 6, 2015

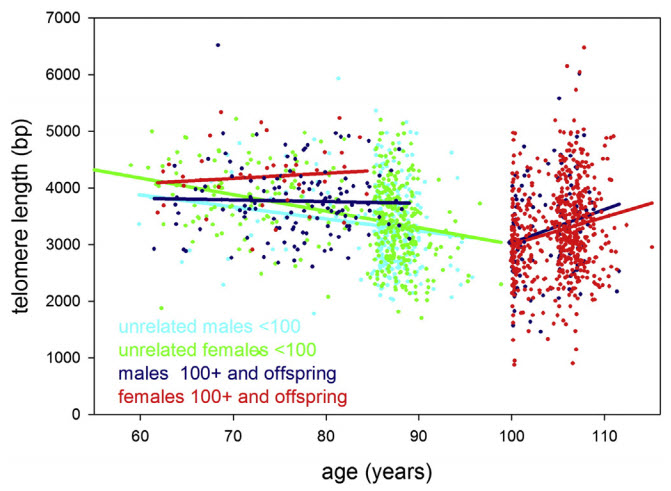

Leukocyte (white blood cell) telomere length in study participants up to 115 years of age. Statistical regression lines belonging to these groups are indicated by the same color as the data. (credit: Yasumichi Arai et al./EBioMedicine)

Scientists say they have cracked the secret of why some people live a healthy and physically independent life over the age of 100: keeping inflammation down and telomeres long.

Newcastle University’s Institute for Ageing in the U.K. and Keio University School of Medicine note that severe inflammation is part of many diseases in the old, such as diabetes or diseases attacking the bones or the body’s joints, and chronic inflammation can develop from any of them.

The study was published online in an open-access paper in EBioMedicine, a new open-access journal jointly supported by the journals Cell and Lancet.

“Centenarians and supercentenarians are different,” said Professor Thomas von Zglinicki, from Newcastle University’s Institute for Ageing, and lead author. “Put simply, they age slower. They can ward off diseases for much longer than the general population.”

Keeping telomeres long

The researchers studied groups of people aged 105 and over (semi-supercentenarians), those 100 to 104 (centenarians), and those nearly 100 and their offspring. They measured a number of health markers they believe contribute towards successful aging, including blood cell numbers, metabolism, liver and kidney function, inflammation, and telomere length.

Scientists expected to see a continuous shortening of telomeres with age. But what they found was that the children of centenarians, who have a good chance of becoming centenarians themselves, maintained their telomeres at a “youthful” level corresponding to about 60 years of age — even when they became 80 or older.

“Our data reveals that once you’re really old [meaning centenarians and those older than 100], telomere length does not predict further successful aging, said von Zglinicki. “However, it does show that [they] maintain their telomeres better than the general population, which suggests that keeping telomeres long may be necessary or at least helpful to reach extreme old age.”

Lower inflammation levels

Centenarian offspring maintained lower levels of markers for chronic inflammation. These levels increased in the subjects studied with age including centenarians and older, but those who were successful in keeping previously keeping them low had the best chance to maintain good cognition, independence, and longevity.

“It has long been known that chronic inflammation is associated with the aging process in younger, more ‘normal’ populations, but it’s only very recently we could mechanistically prove that inflammation actually causes accelerated aging in mice,” von Zglinicki said.

“This study, showing for the first time that inflammation levels predict successful aging even in the extreme old, makes a strong case to assume that chronic inflammation drives human aging too. … Designing novel, safe anti-inflammatory or immune-modulating medication has major potential to improve healthy lifespan.”

Data from three studies combined

Data was collated by combining three community-based group studies: Tokyo Oldest Old Survey on Total Health, Tokyo Centenarians Study, and Japanese Semi-Supercentenarians Study.

The research comprised 1,554 individuals, including 684 centenarians and (semi-) supercentenarians, 167 pairs of offspring and unrelated family of centenarians, and 536 very old people. The total group covered ages from around 50 up to the world’s oldest man at 115 years.

However, “presently available potent anti-inflammatories are not suited for long-term treatment of chronic inflammation because of their strong side-effects,” said Yasumichi Arai, Head of the Tokyo Oldest Old Survey on Total Health cohort and first author of the study.

Abstract of Inflammation, But Not Telomere Length, Predicts Successful Ageing at Extreme Old Age: A Longitudinal Study of Semi-supercentenarians

To determine the most important drivers of successful ageing at extreme old age, we combined community-based prospective cohorts: Tokyo Oldest Old Survey on Total Health (TOOTH), Tokyo Centenarians Study (TCS) and Japanese Semi-Supercentenarians Study (JSS) comprising 1554 individuals including 684 centenarians and (semi-)supercentenarians, 167 pairs of centenarian offspring and spouses, and 536 community-living very old (85 to 99 years). We combined z scores from multiple biomarkers to describe haematopoiesis, inflammation, lipid and glucose metabolism, liver function, renal function, and cellular senescence domains. In Cox proportional hazard models, inflammation predicted all-cause mortality with hazard ratios (95% CI) 1.89 (1.21 to 2.95) and 1.36 (1.05 to 1.78) in the very old and (semi-)supercentenarians, respectively. In linear forward stepwise models, inflammation predicted capability (10.8% variance explained) and cognition (8.6% variance explained) in (semi-) supercentenarians better than chronologic age or gender. The inflammation score was also lower in centenarian offspring compared to age-matched controls with Δ (95% CI) = − 0.795 (− 1.436 to − 0.154). Centenarians and their offspring were able to maintain long telomeres, but telomere length was not a predictor of successful ageing in centenarians and semi-supercentenarians. We conclude that inflammation is an important malleable driver of ageing up to extreme old age in humans.