Silver-nanowire filters provide clean water for the developing world

September 9, 2010

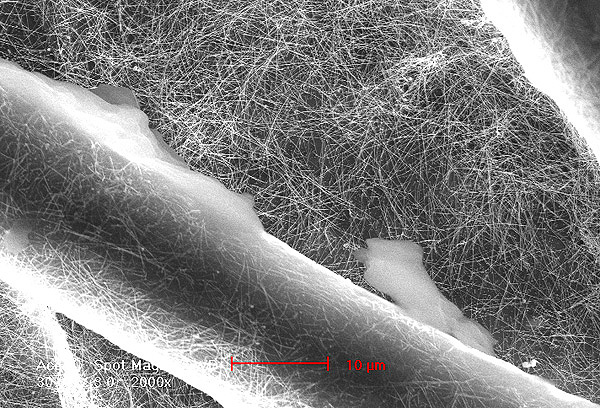

A scanning electron microscope image of the silver nanowires in which the cotton is dipped during the process of constructing a filter. The large fibers are cotton. (Yi Cui)

Stanford researchers have developed a water-purifying filter that makes the process more than 80,000 times faster than existing filters. The key is coating the filter fabric – ordinary cotton – with nanotubes and silver nanowires, then electrifying it. The filter uses very little power, has no moving parts and could be used throughout the developing world.

Instead of physically trapping bacteria as most existing filters do, the new filter lets them flow on through with the water. But by the time the pathogens have passed through, they have also passed on, because the device kills them with an electrical field that runs through the highly conductive “nano-coated” cotton.

“This really provides a new water treatment method to kill pathogens,” said Yi Cui, an associate professor of materials science and engineering. “It can easily be used in remote areas where people don’t have access to chemical treatments such as chlorine.”

Cholera, typhoid and hepatitis are among the waterborne diseases that are a continuing problem in the developing world. Cui said the new filter could be used in water purification systems from cities to small villages.

Faster filtering by letting bacteria through

Filters that physically trap bacteria must have pore spaces small enough to keep the pathogens from slipping through, but that restricts the filters’ flow rate.

Since the new filter doesn’t trap bacteria, it can have much larger pores, allowing water to speed through at a more rapid rate.

“Our filter is about 80,000 times faster than filters that trap bacteria,” Cui said. He is the senior author of a paper describing the research that will be published in an upcoming issue of Nano Letters. The paper is available online now.

The larger pore spaces in Cui’s filter also keep it from getting clogged, which is a problem with filters that physically pull bacteria out of the water.

The big advantage of the nanomaterials is that their small size makes it easier for them to stick to the cotton, Cui said. The nanowires range from 40 to 100 billionths of a meter in diameter and up to 10 millionths of a meter in length. The nanotubes were only a few millionths of a meter long and as narrow as a single billionth of a meter. Because the nanomaterials stick so well, the nanotubes create a smooth, continuous surface on the cotton fibers. The longer nanowires generally have one end attached with the nanotubes and the other end branching off, poking into the void space between cotton fibers.

“With a continuous structure along the length, you can move the electrons very efficiently and really make the filter very conducting,” he said. “That means the filter requires less voltage.”

The research was funded by the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST).

More info: Stanford University news