Smartphones not so smart for learning?

July 7, 2015

Smartphones distracted students from school-related tasks in self-reported results of a one-year study of first-time smartphone users at a major research university in Texas.

“Smartphone technology is penetrating world markets and becoming abundant in most college settings,” said Philip Kortum, assistant professor of psychology at Rice and the study’s co-author. “We were interested to see how students with no prior experience using smartphones thought [smartphones] impacted their education.”

The research, published in the British Journal of Educational Technology, revealed that while users initially believed the mobile devices (2011 iPhones, in this study) would improve their ability to perform well with homework and tests and ultimately get better grades, the opposite was reported at the end of the study.

Kortum said that the study’s findings have important implications for the use of technology in education, but that the research did not address the structured use of smartphones in an educational setting. “Previous studies have provided ample evidence that when smartphones are used with specific learning objects in mind, they can significantly enhance the learning experience.”

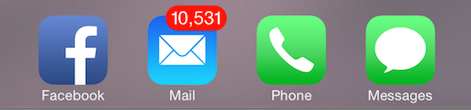

Not surprisingly, “over 65% of all application launches consisted of opening the top four communication/social

applications: text messaging (SMS), voice phone, email and Facebook … almost half of this percentage is accounted for by the Messages application,” the researchers note in the paper. Apps most installed (48 percent of students): AngryBirds and WordsWithFriends games.

The work was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Abstract of You can lead a horse to water but you cannot make him learn: Smartphone use in higher education

Smartphone technology is penetrating world markets and becoming ubiquitous in most college settings. This study takes a naturalistic approach to explore the use of these devices to support student learning. Students that had never used a smartphone were recruited to participate and reported on their expectations of the value of smartphones to achieve their educational goals. Instrumented iPhones that logged device usage were then distributed to these students to use freely over the course of 1 year. After the study, students again reported on the actual value of their smartphones to support their educational goals. We found that students’ reports changed substantially before and after the study; specifically, the utility of the smartphone to help with education was perceived as favorable prior to use, and then, by the end of the study, they viewed their phones as detrimental to their educational goals. Although students used their mobile device for informal learning and access to school resources according to the logged data, they perceived their iPhones as a distraction and a competitor to requisite learning for classroom performance.