Stem cell versatility could help tissue regeneration

August 19, 2010

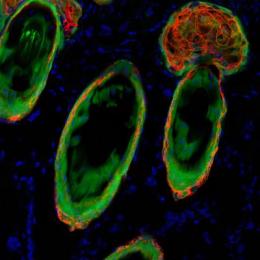

This cross-section of skin shows rat thymic epithelial cells (green) contributing to hair follicles and sebaceous glands. (EPFL)

European scientists have reprogrammed stem cells from the thymus to grow skin and hair cells, in a development that could have implications for tissue regeneration. Their research shows that it is possible to convert one stem type to another without the need for genetic modification.

The researchers, who used rat models, grew stem cells from the thymus in the laboratory using conditions for growing hair follicle skin stem cells. When the cells were transplanted into developing skin, they were able to maintain skin and hair for more than a year, and the genetic markers of the cells changed to be more similar to those of hair follicle stem cells.

The research, by a team from the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland and the University of Edinburgh’s Medical Research Council Centre for Regenerative Medicine, was published in the journal Nature. It shows that triggers from the surrounding environment — in this case from the skin — can reprogram stem cells to become tissues they are not normally able to generate.

Crossing germ layer boundaries

When an animal develops, embryos form three cellular or germ layers — ectoderm, endoderm and mesoderm — which then go on to form the body’s organs and tissues.

Ectoderm becomes skin and nerves, endoderm becomes the gut and organs such as the liver, pancreas and thymus, and mesoderm becomes muscle, bones and blood.

Until now it was believed that germ layer boundaries could not be crossed — that cells originating in one germ layer could not develop into cells associated with one of the others.

This latest research shows that thymus cells, originating from the endoderm, can turn in to skin stem cells, which originate from the ectoderm origin. This suggests germ layer boundaries are less absolute than previously thought.

Dr Clare Blackburn, of the University of Edinburgh’s Medical Research Council Centre for Regenerative Medicine, said: “It’s not just that a latent capacity is triggered or uncovered when these stem cells come in to contact with skin. They really change track — expressing different genes and becoming more potent. It will be interesting to see whether microenvironments other than skin have a similar effect.”

More info: University of Edinburgh news