Testing for bacteria in minutes instead of weeks

July 2, 2013

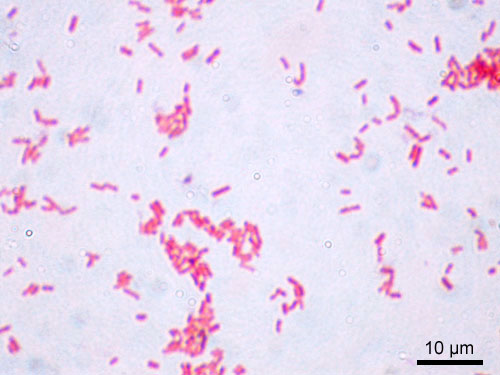

Microscopic image of Escherichia coli bacteria (credit: Y_tambe/Wikimedia Commons)

EPFL researchers have built a matchbox-sized device that can test for the presence of bacteria in a couple of minutes, instead of up to several weeks.

A nano-lever vibrates in the presence of bacterial activity, while a laser reads the vibration and translates it into an electrical signal that can be easily read: absence of a signal signifies the absence of bacteria.

This makes it quick and easy for clinics to determine if a bacteria has been effectively treated by an antibiotic.

For doctors, it’s a tool for testing chemotherapy treatment and for determining the right dosage of antibiotics. And researchers can determine which treatments are the most effective, explains EPFL’s Giovanni Dietler.

Researchers are currently evaluating the tool’s potential in oncology. They are looking into measuring the metabolism of tumor cells that have been exposed to cancer treatment to evaluate the efficiency of the treatment.

Detecting a flat line

The researchers place the bacteria on an extremely sensitive measuring device that vibrates a small lever, which vibrates under the metabolic activity of the bacteria. These small oscillations, on the order of one millionth of a millimeter, determine the presence or absence of the bacteria.

To measure these vibrations, the researchers project a laser onto the lever. The light is then reflected back and the signal is converted into an electrical current to be interpreted by the clinician or researcher. When the electrical current is a flat line, one knows that the bacteria are all dead; it is as easy to read as an electrocardiogram.

“By joining our tool with a piezoelectric device instead of a laser, we could further reduce its size to the size of a microchip,” says Dietler. “They could then be combined together to test a series of antibiotics on one strain in only a couple of minutes.”

A thermal conductivity test

Meanwhile, mechanical engineers from Pohang University of Science and Technology in Korea have discovered a way to measure the “thermal conductivity” of three types of cells taken from human and rat tissues and placed in individual micro-wells. They showed that they could detect uniform heat signatures from the various cells and measured significant difference between dead and living ones, suggesting a new way to probe cells for biological activity.

“In the short-term, this biosensing technique can be used to measure cell viability,” said Kim. “In the long term, we hope to refine it to develop a non-invasive, rapid means for early diagnosis of diseases such as cancer based on differences in the thermal properties of cells.”