The case for optionally manned aircraft

September 18, 2012

Purely manned or purely unmanned aircraft possess various inherent advantages and limitations. Optionally manned aircraft provide the best of both worlds, allowing commanders to employ force at various risk levels and to employ their aircraft and crews to their fullest capacities, says Lt. Col. Peter Garretson in Armed Forces Journal.

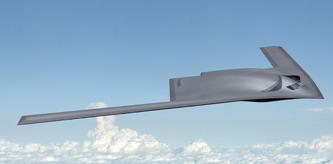

Such platforms — and in particular, the planned Long Range Strike-Bomber (LRS-B) — represent the lowest-cost, lowest-risk path toward a future of greater platform autonomy and technical and strategic advantage, he says.

Preparing for Progress

According to Garretson and the experts he cites:

- Today’s technology is insufficient to allow unmanned aircraft to make independent, complex judgments in an ambiguous and novel environment and so must be tethered to human judgment. But data links can be denied or deceived, and in any case, they introduce seconds of delay that can be crucial, such as when prosecuting moving targets or surviving in well-defended airspace.

- In theory, some of these limitations ought to erode as unmanned technology develops. Research into artificially intelligent moral reasoning that might one day allow autonomous application of rules of engagement in complex situations. Finally, the history of electronics suggests that after 2020, computational power roughly equal to that of a human brain may be available to consumers for about what we pay today for a decent laptop.

- The best option is to build future platforms “autonomy ready” — that is, so local or remote pilots could be replaced by artificial intelligence through software upgrades rather than costly hardware retrofits or new platforms.

- By allowing human crews to ride along as unmanned aircraft grow larger and their autonomic systems more capable, optionally manned aircraft create a space to build the trust that permits change.

- Today, unmanned systems are not trusted to plan their own missions, interpret rules of engagement or decide to employ weapons and lethal force, but the trends in computation and unmanned technology argue it will not be the case in the future.

- Assuming the Air Force plans to buy 80 to 100 LRS-Bs at a target unit cost of $550 million, the additional cost to allow it to be remotely piloted would increase the price by less than 1 percent (mostly for communication equipment), representing an opportunity cost of one aircraft (99 instead of the planned 100).

- Designing in the ability to gradually fly the aircraft without aircrew aboard will likely reduce manpower and training costs over its decades of service. (Rroughly 70 percent of an aircraft’s program cost is not in acquisition but operation; currently, the Air Force spends about 43 percent of its “blue” dollars on operations and support and 23 percent on manpower.)