The Google of material properties

December 22, 2011

Thanks to a new online toolkit developed at MIT and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, any researcher can now find a material with specific desired properties far more easily than ever before.

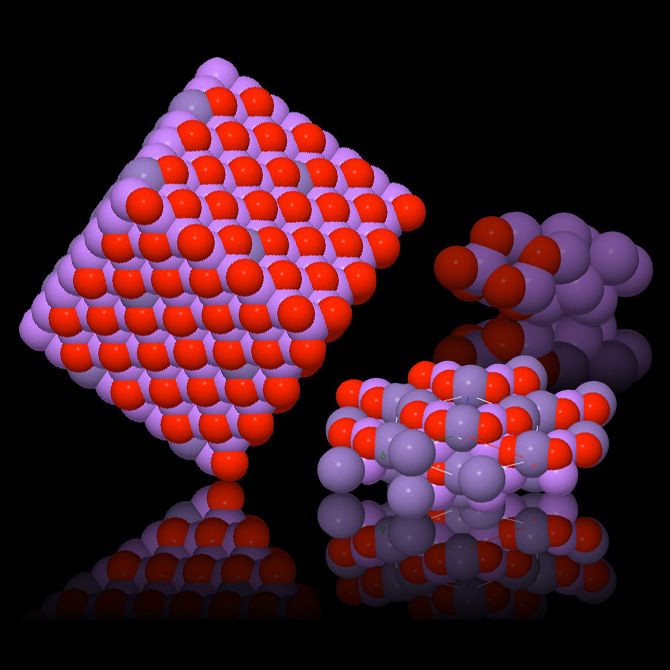

Using a website called the Materials Project, you can explore an ever-growing database of more than 18,000 chemical compounds.

The site’s tools can quickly predict how two compounds will react with one another, what that composite’s molecular structure will be, and how stable it would be at different temperatures and pressures.

The new tool could revolutionize product development in fields from energy to electronics to biochemistry, its developers say, much as search engines have transformed the ability to search for arcane bits of knowledge.

The project is a direct outgrowth of MIT’s Materials Genome Project, initiated in 2006 by Gerbrand Ceder, the Richard P. Simmons (1953) Professor of Materials Science and Engineering. The idea, he says, is that the site “would become the Google of material properties,” making available data previously scattered in many different places, most of them not even searchable.

For example, it used to require months of work — consulting tables of data, performing calculations and carrying out precise lab tests — to create a single phase diagram showing when compounds incorporating several different elements would be solid, liquid or gas. Now, such a diagram can be generated in a matter of minutes, Ceder says.

U.S. Secretary of Energy Steven Chu said in a press release announcing the Materials Project’s launch that it could “drive discoveries that not only help power clean energy, but are also used in common consumer products. This accelerated process could potentially create new domestic industries.”

Developing new materials for clean energy, transportation, electronics, and other fields could be the key to revitalizing the American manufacturing industry and giving the nation a new competitive edge, he said.

Dial-a-material

The Materials Project is much more than a database of known information, Ceder says: The tool computes many materials’ properties in real time, upon request, using the vast supercomputing capacity of the Lawrence Berkeley Lab. “We still don’t know most of the properties of most materials,” he says, but adds that in many cases these can be derived from known formulas and principles.

Already, more than 500 researchers from universities, research labs and companies have used the new system to seek new materials for lithium-ion batteries, photovoltaic cells and new lightweight alloys for use in cars, trucks and airplanes. The Materials Project is available for use by anyone, although users must register (free of charge) in order to spend more than a few minutes, or to use the most advanced features.

There are about 100,000 known inorganic compounds, Ceder says; using the computational tools incorporated into this project, “it is now within reach to calculate properties over the whole known universe of compounds.” He adds that this achievement makes possible, for the first time, the development of an exhaustive database of material properties derived from the fundamental equations of basic physics.

“This is what the field [of materials science] has been working on for 30 years,” Ceder says. Starting in the 1980s, “people started to develop predictive models that were more than accurate enough to make decisions on. You can predict voltage, stability, mobility of ions” and many other properties, he says, although other properties “are still challenging” to predict this way.

The tools could also make a big difference in education, Ceder says: When professors set up experiments to help students learn specific principles, “it used to be that we had to pick easy examples” with known outcomes, he says. Now, it’s possible to set much more challenging exercises.

“Lack of information was a real problem in materials science,” Ceder says. When a company needed to come up with a new material for a battery or a building or a consumer product, in many cases this required starting from scratch, because even information about materials that had already been studied was so hard to locate. “I really do think this will transform the way people do materials research,” Ceder says.

Mark Obrovac, an associate professor of chemistry and physics at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, says, “The Materials Project has made complex computational techniques available to materials researchers at a click of a mouse. This is a major innovation in materials science, enabling researchers to rapidly predict the structure and properties of materials before they make them, and even of materials that cannot be made. This can significantly accelerate materials development in many important areas, including advanced batteries, microelectronics and telecommunications.”