The ‘ultimate discovery tool’ for nanoparticles

June 24, 2016

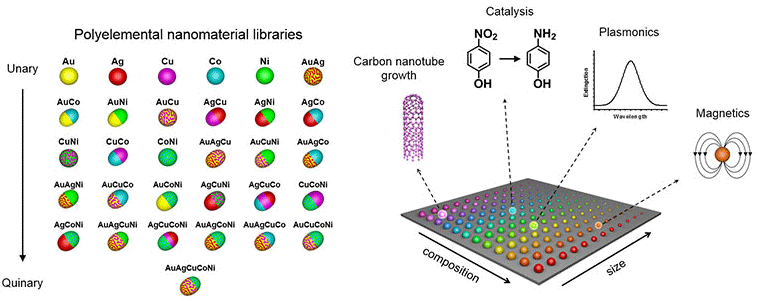

A combinatorial library of polyelemental nanoparticles was developed using Dip-Pen Nanolithography, opening up a new field of nanocombinatorics for rapid screening of nanomaterials for a multitude of properties. (credit: Peng-Cheng Chen/James Hedrick)

The discovery power of the gene chip is coming to nanotechnology, as a Northwestern University research team develops a tool to rapidly test millions — and perhaps even billions — of different nanoparticles at one time to zero in on the best nanoparticle for a specific use.

When materials are miniaturized, their properties — optical, structural, electrical, mechanical and chemical — change, offering new possibilities. But determining what nanoparticle size and composition are best for a given application, such as catalysts, biodiagnostic labels, pharmaceuticals and electronic devices, is a daunting task.

“As scientists, we’ve only just begun to investigate what materials can be made on the nanoscale,” said Northwestern’s Chad A. Mirkin, a world leader in nanotechnology research and its application, who led the study. “Screening a million potentially useful nanoparticles, for example, could take several lifetimes. Once optimized, our tool will enable researchers to pick the winner much faster than conventional methods. We have the ultimate discovery tool.”

Combinatorial libraries of nanoparticles

Using a Northwestern technique that deposits materials on a surface, Mirkin and his team figured out how to make combinatorial libraries of nanoparticles in a controlled way. (A combinatorial library is a collection of systematically varied structures encoded at specific sites on a surface.) Their study was published today (June 24) by the journal Science.

The nanoparticle libraries are much like a gene chip, Mirkin says, where thousands of different spots of DNA are used to identify the presence of a disease or toxin. Thousands of reactions can be done simultaneously, providing results in just a few hours. Similarly, Mirkin and his team’s libraries will enable scientists to rapidly make and screen millions to billions of nanoparticles of different compositions and sizes for desirable physical and chemical properties.

“The ability to make libraries of nanoparticles will open a new field of nanocombinatorics, where size — on a scale that matters — and composition become tunable parameters,” Mirkin said. “This is a powerful approach to discovery science.”

Mirkin is the George B. Rathmann Professor of Chemistry in the Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences and founding director of Northwestern’s International Institute for Nanotechnology.

Using just five metallic elements — gold, silver, cobalt, copper and nickel — Mirkin and his team developed an array of unique structures by varying every elemental combination. In previous work, the researchers had shown that particle diameter also can be varied deliberately on the 1- to 100-nanometer length scale.

More than half never existed before on Earth

Synthesis of multimetallic NPs and a five-element library of unary and multimetallic NPs (credit: Peng-Cheng Chen et al./Science)

Some of the compositions can be found in nature, but more than half of them have never existed before on Earth. And when pictured using high-powered imaging techniques, the nanoparticles appear like an array of colorful Easter eggs, each compositional element contributing to the palette.

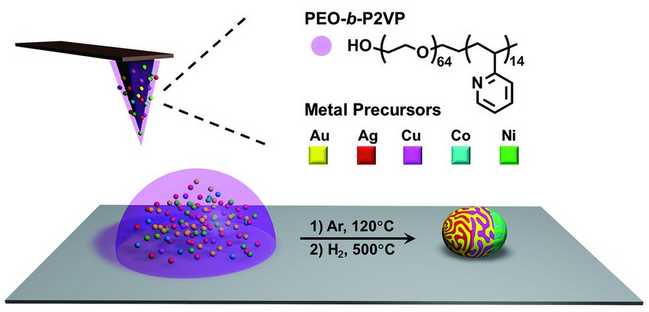

To build the combinatorial libraries, Mirkin and his team used Dip-Pen Nanolithography, a technique developed at Northwestern in 1999, to deposit onto a surface individual polymer “dots,” each loaded with different metal salts of interest. The researchers then heated the polymer dots, reducing the salts to metal atoms and forming a single nanoparticle. The size of the polymer dot can be varied to change the size of the final nanoparticle.

The researchers used the tool to systematically generate a library of 31 nanostructures using the five different metals. They then used advanced electron microscopes to spatially map the compositional trajectories of the combinatorial nanoparticles.

The next materials to power fuel cells, efficiently harvest solar energy, or create new chips

Scientists can now begin to study these nanoparticles as well as build other useful combinatorial libraries consisting of billions of structures that subtly differ in size and composition. These structures may become the next materials that power fuel cells, efficiently harvest solar energy and convert it into useful fuels, and catalyze reactions that take low-value feedstocks from the petroleum industry and turn them into high-value products useful in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries.

Mirkin is a member of the Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University as well as co-director of the Northwestern University Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence. He also is a professor of medicine, chemical and biological engineering, biomedical engineering and materials science at Northwestern.

The research was supported by GlaxoSmithKline, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research,and the Asian Office of Aerospace R&D.

Abstract of Polyelemental nanoparticle libraries

Multimetallic nanoparticles are useful in many fields, yet there are no effective strategies for synthesizing libraries of such structures, in which architectures can be explored in a systematic and site-specific manner. The absence of these capabilities precludes the possibility of comprehensively exploring such systems. We present systematic studies of individual polyelemental particle systems, in which composition and size can be independently controlled and structure formation (alloy versus phase-separated state) can be understood. We made libraries consisting of every combination of five metallic elements (Au, Ag, Co, Cu, and Ni) through polymer nanoreactor–mediated synthesis. Important insight into the factors that lead to alloy formation and phase segregation at the nanoscale were obtained, and routes to libraries of nanostructures that cannot be made by conventional methods were developed.