Toxic interaction in neurons that leads to dementia and ALS

December 12, 2012

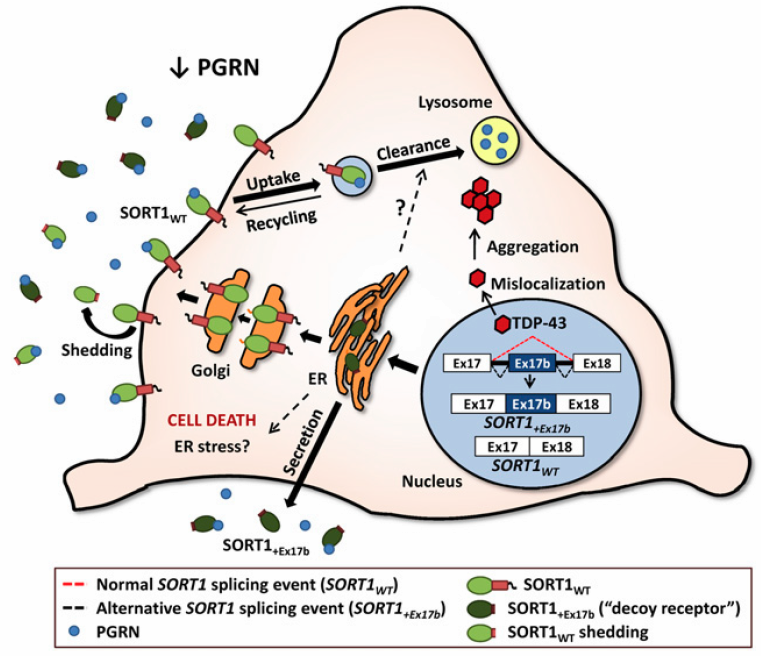

Theoretical model illustrating how misregulation of human SORT1 splicing affects PGRN levels (credit: Mercedes Prudencio et al./PNAS)

Researchers at Mayo Clinic in Florida have uncovered a toxic cellular process by which a protein that maintains the health of neurons becomes deficient and can lead to dementia.

The findings shed new light on the link between culprits implicated in two devastating neurological diseases: Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, which afflicts physicist Stephen Hawking.

There is no cure for frontotemporal dementia, a disorder that affects personality, behavior and language and is second only to Alzheimer’s disease as the most common form of early-onset dementia.

While much research is devoted to understanding the role of each defective protein in these diseases, the team at Mayo Clinic took a new approach to examine the interplay between TDP-43, a protein that regulates messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) — biological molecules that carry the information of genes and are used by cells to guide protein synthesis — and sortilin (SORT), which regulates the protein progranulin.

“We sought to investigate how TDP-43 regulates the levels of the protein progranulin, given that extreme progranulin levels at either end of the spectrum, too low or too high, can respectively lead to neurodegeneration or cancer,” says the study’s lead investigator, Mercedes Prudencio, Ph.D., a neuroscientist at the Mayo Clinic campus in Florida.

The neuroscientists found that a lack of the protein TDP-43, long implicated in frontotemporal dementia and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, leads to elevated levels of defective sortilin mRNA. The research team is the first to identify significantly elevated levels of the defective sortilin mRNA in autopsied human brain tissue of frontotemporal dementia/TDP cases, the most common subtype of the disease.

“We found a lack of TDP-43 disrupts the cellular process called mRNA splicing that precedes protein synthesis, resulting in the generation of a defective sortilin protein,” Dr. Prudencio says. “More important, the defective sortilin binds to progranulin and as a result deprives neurons of progranulin’s protective effects that stave off the cell death associated with disease.”

By improving the scientific community’s understanding of the biological processes leading to frontotemporal dementia, the researchers have also paved the way for the development of new therapies to prevent or combat the disease, says Leonard Petrucelli, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Neuroscience at Mayo Clinic in Florida, who led the research.

The research at Mayo Clinic in Florida was financed by the Mayo Clinic Foundation, National Institutes of Health, and National Institute on Aging, ALS Association, and the Department of Defense.