Turning off the sensation of cold

February 14, 2013

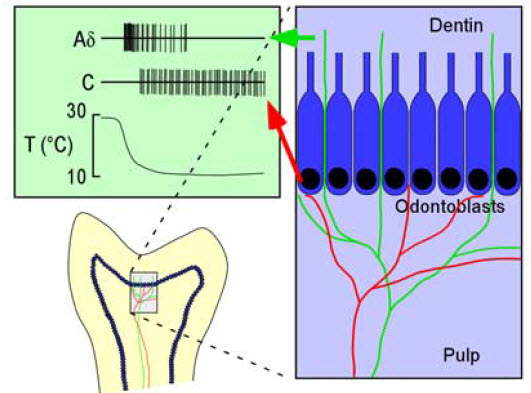

Schematic diagram of mouse molars indicating the termination zones of cold-sensitive fibers (red and green) localized in the pulp and dentin, respectively. The two types of fibers fire with distinct rates of discharge, latencies, and adaptation, as depicted in green box. (Credit: Yoshio Takashima et al./The Journal of Neuroscience)

USC neuroscientists have isolated chills at a cellular level, identifying the sensory network of neurons in the skin that relays the sensation of cold.

David McKemy, associate professor of neurobiology in the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, and his team managed to selectively shut off the ability to sense cold in mice while still leaving them able to sense heat and touch.

In prior work, McKemy discovered a link between the experience of cold and a protein known as TRPM8 (pronounced trip-em-ate), which is a sensor of cold temperatures in neurons in the skin, as well as a receptor for menthol, the cooling component of mint.

Now they have isolated and ablated (destroyed the function of) the neurons that express TRPM8, giving researchers the ability to test the function of these specific cells.

The researchers tested control mice and mice without TRPM8 neurons on a multi-temperature surface. The surface temperature ranged from 0 degrees to 50 degrees Celsius (32 to 122 degrees Farenheit), and mice were allowed to move freely among the regions.

The researchers found that mice depleted of TRPM8 neurons could not feel cold, but still responded to heat. Control mice tended to stick to an area around 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) and avoided both colder and hotter areas. But mice without TRPM8 neurons avoided only hotter plates and not cold — even when the cold should have been painful or was potentially dangerous.

By better understanding the specific ways in which we feel sensations, scientists hope to one day develop better pain treatments without knocking out all ability to feel for suffering patients.

“The problem with pain drugs now is that they typically just reduce inflammation, which is just one potential cause of pain, or they knock out all sensation, which often is not desirable,” McKemy said. “One of our goals is to pave the way for medications that address the pain directly, in a way that does not leave patients completely numb.”

Funding for this research came from the National Institutes of Health.