Ultrasound jump-starts brain of man in coma

August 26, 2016

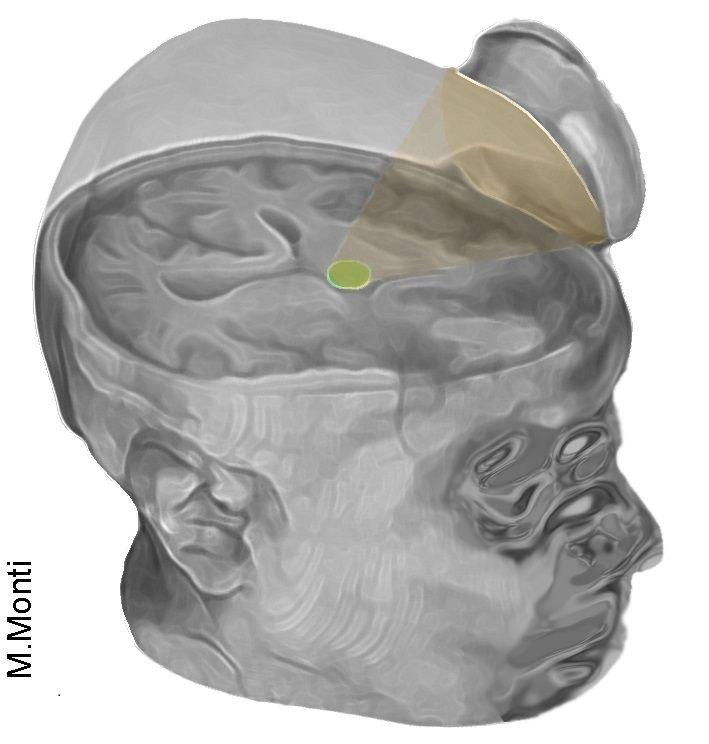

The non-invasive technique uses ultrasound to target the brain’s thalamus (credit: Martin Monti/UCLA)

UCLA neurosurgeons used ultrasound to “jump-start” the brain of a 25-year-old man from a coma, and he has made remarkable progress following the treatment.

The technique, called “low-intensity focused ultrasound pulsation” (LIFUP), works non-invasively and without affecting intervening tissues. It excites neurons in the thalamus, an egg-shaped structure that serves as the brain’s central hub for processing information.

“It’s almost as if we were jump-starting the neurons back into function,” said Martin Monti, the study’s lead author and a UCLA associate professor of psychology and neurosurgery. “Until now, the only way to achieve this was a risky surgical procedure known as deep brain stimulation, in which electrodes are implanted directly inside the thalamus,” he said. “Our approach directly targets the thalamus but is noninvasive.”

What about using it on vegetative or minimally conscious patients?

Monti cautioned that the procedure requires further study on additional patients before the scientists can determine whether it could be used consistently to help other people recovering from comas.

“It is possible that we were just very lucky and happened to have stimulated the patient just as he was spontaneously recovering,” Monti said.

If the technology helps other people recovering from coma, Monti said, it could eventually be used to build a portable device — perhaps incorporated into a helmet — as a low-cost way to help “wake up” patients, perhaps even those who are in a vegetative or minimally conscious state (MCS). Currently, there is almost no effective treatment for such patients, he said.

Israel Stinson (credit: Life Legal Defense Foundation)

On Thursday August 25, two year-old Israel Stinson, whose fight for life gained international attention, died Thursday after doctors at Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles removed him from a breathing ventilator against his parents’ wishes, after a Los Angeles Superior Court judge removed a restraining order, the Los Angeles Times reports.

It’s not clear, going forward, why doctors or the FDA could ethically refuse to provide “compassionate access” to a treatment such as LIFUP as a last resort before pulling the plug.

Speculation: brain hackers will start (have started?) experimenting with LIFUP as a brain stimulant.

“Foggy from all-night cramming for midterms? LIFUP it!”

Safer than DBS and tDCS

A report on the treatment is published in the journal Brain Stimulation. This is the first time the approach has been used to treat severe brain injury.

The authors note that the new technique combines the advantages of highly invasive deep brain stimulation (DBS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) while avoiding their respective disadvantages.

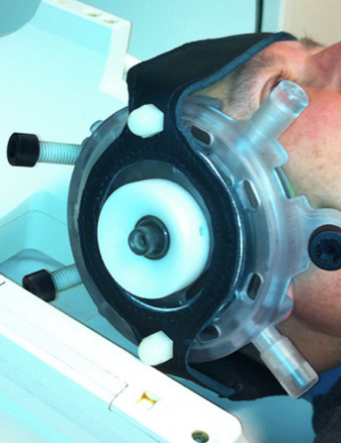

Low-intensity focused ultrasound pulsation (credit: Brainsonix)

The procedure was pioneered by Alexander Bystritsky, a UCLA professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences in the Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior and a co-author of the study.

Bystritsky is also a founder of Brainsonix, a Sherman Oaks, California-based company that provided the device (BXPulsar 1001) the researchers used in the study.

That device, about the size of a coffee cup saucer, creates a small sphere of acoustic energy that can be aimed at different regions of the brain to excite brain tissue.

For the new study, researchers placed it by the side of the man’s head and activated it 10 times for 30 seconds each, in a 10-minute period.

Monti said the device is safe because it emits only a small amount of energy — less than a conventional Doppler ultrasound.

“First-in-man” clinical trial

Before the procedure began, the man showed only minimal signs of being conscious and of understanding speech. For example, he could perform small, limited movements when asked. By the day after the treatment, his responses had improved measurably.

Three days later, the patient had regained full consciousness and full language comprehension, and he could reliably communicate by nodding his head “yes” or shaking his head “no,” consistent with emergence from MCS (eMCS). He even made a fist-bump gesture to say goodbye to one of his doctors.

“The changes were remarkable,” Monti said.

The technique targets the thalamus because, in people whose mental function is deeply impaired after a coma, thalamus performance is typically diminished. Medications that are commonly prescribed to people who are coming out of a coma only indirectly target the thalamus.

Under the direction of Paul Vespa, a UCLA professor of neurology and neurosurgery at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, the researchers plan to test the procedure on several more people beginning this fall at the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. Those tests will be conducted in partnership with the UCLA Brain Injury Research Center and funded in part by the Dana Foundation and the Tiny Blue Dot Foundation.

UPDATE 8/29/2016: clarified depth of coma

Abstract of Non-Invasive Ultrasonic Thalamic Stimulation in Disorders of Consciousness after Severe Brain Injury: A First-in-Man Report

Modern intensive care medicine has greatly increased the rates of survival after severe brain injury (BI). Nonetheless, a number of patients fail to fully recover from coma, and awaken to a disorder of consciousness (DOC) such as the vegetative state (VS) or the minimally conscious state (MCS) [1]. In these conditions, which can be transient or last indefinitely, patients can lose virtually all autonomy and have almost no treatment options [1,2]. In addition, these conditions place great emotional and financial strain on families, lead to increased burn-out rates among care-takers, impose financial stress on medical structures and public finances due to the costs of prolonged intensive care, and raise difficult legal and ethical questions [3].