Wait, some stem cells use nanotubes to communicate with other cells? Seriously?

July 1, 2015

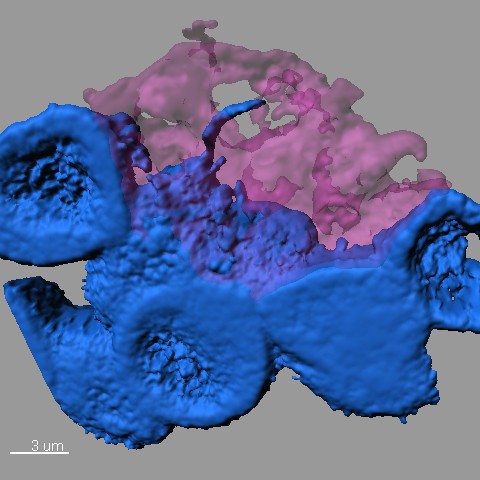

Confocal microscope image showing stem cells (blue) clustering around a hub (pink) in the stem cell niche (pink) as one stem cell extends a nanotube into the hub (credit: Mayu Inaba, University of Michigan)

Certain types of stem cells use microscopic, threadlike nanotubes to communicate with neighboring cells, rather than sending a broadcast signal, researchers at University of Michigan Life Sciences Institute and University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center have discovered.

The fruit-fly research findings, published today (July 1) in Nature, suggest that short-range, cell-to-cell communication may rely on this type of direct connection more than was previously understood, said co-senior author Yukiko Yamashita, a U-M developmental biologist.

“There are trillions of cells in the human body, but nowhere near that number of signaling pathways,” she said. “There’s a lot we don’t know about how the right cells get just the right messages to the right recipients at the right time.”

Hidden in plain sight

The investigation began when a postdoctoral researcher in Yamashita’s lab, Mayu Inaba, approached her mentor with questions about tiny threads of connection she noticed in an image of fruit fly reproductive stem cells, which are also known as germ line cells. The projections linked individual stem cells back to a central hub in the stem cell “niche.” Niches create a supportive environment for stem cells and help direct their activity.

Yamashita, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, MacArthur Fellow and an associate professor at the U-M Medical School, looked through her old image files and discovered that the connections appeared in numerous images.

“I had seen them, but I wasn’t seeing them,” Yamashita said. “They were like a little piece of dust on an otherwise normal picture. After we presented our findings at meetings, other scientists who work with the same cells would say, ‘We see them now, too.'”

It’s not surprising that the minute structures went overlooked for so long. Each one is about 3 micrometers long; by comparison, a piece of paper is 100 micrometers thick.

While the study looked specifically at reproductive cells in male Drosophila fruit flies, there have been indications of similar structures in other contexts, including mammalian cells, Yamashita said.

The findings also shed new light on a key attribute of stem cells: their ability to make new specialized cells while still retaining their identity as stem cells.

Germ line stem cells typically divide asymmetrically. In the male fruit fly, when a stem cell divides, one part stays attached to the hub and remains a stem cell. The other part moves away from the hub and begins differentiation into a fly sperm cell.

Until the discovery of the nanotubes, scientists had been puzzled as to how cellular signals guiding identity could act on one of the cells but not the other, said collaborator Michael Buszczak, an associate professor of molecular biology at UT Southwestern, who shares corresponding authorship of the paper and currently co-mentors Inaba with Yamashita.

The researchers conducted experiments that showed disruption of nanotube formation compromised the ability of the germ line stem cells to renew themselves.

The work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the MacArthur Foundation.

Abstract of Nanotubes mediate niche–stem-cell signalling in the Drosophila testis

Stem cell niches provide resident stem cells with signals that specify their identity. Niche signals act over a short range such that only stem cells but not their differentiating progeny receive the selfrenewing signals1. However, the cellular mechanisms that limit niche signalling to stem cells remain poorly understood. Here we show that the Drosophila male germline stem cells form previously unrecognized structures, microtubule-based nanotubes, which extend into the hub, a major niche component. Microtubule-based nanotubes are observed specifically within germline stem cell populations, and require intraflagellar transport proteins for their formation. The bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) receptor Tkv localizes to microtubule-based nanotubes. Perturbation of microtubule- based nanotubes compromises activation of Dpp signalling within germline stem cells, leading to germline stem cell loss. Moreover, Dpp ligand and Tkv receptor interaction is necessary and sufficient for microtubule-based nanotube formation. We propose that microtubule-based nanotubes provide a novel mechanism for selective receptor–ligand interaction, contributing to the short-range nature of niche–stem-cell signalling.