Warning: Your hospital may kill you and they won’t report it

May 9, 2016

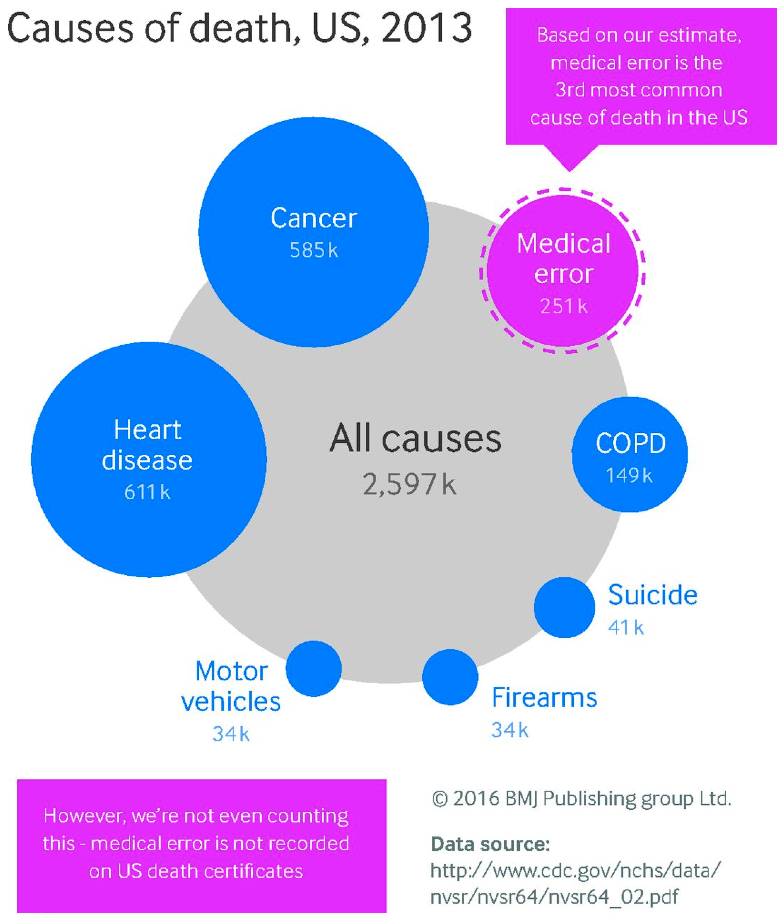

The common causes of death in the United States in 2013 (credit: BMJ)

Medical error is the third leading cause of death in the U.S. after heart disease and cancer — an estimated 210,000 to 400,000 deaths a year among hospital patients — say experts in an open-access paper in the British Medical Journal — despite the fact that both hospital reporting and death certificates in the U.S. have no provision for acknowledging medical error.

Martin Makary and Michael Daniel at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore call for better reporting to help understand the scale of this problem and determine how to tackle it.

Currently, death certification in the U.S. relies on assigning an International Classification of Disease (ICD) code to the cause of death, so causes of death not associated with an ICD code, such as human and system factors, are not captured. According to the World Health Organization, 117 countries code their mortality statistics using the ICD system, including the UK and Canada.

As a result, accurate data on deaths associated with medical error is lacking. However, using studies from 1999 onwards — and extrapolating to the total number of U.S. hospital admissions in 2013 — Makary and Daniel calculated a mean rate of death from medical error of 251,454 a year.

Comparing their estimate to the annual list of the most common causes of death in the U.S., compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suggests that medical error is the third most common cause of death in the US.

Fixing medical errors

“Although we cannot eliminate human error, we can better measure the problem to design safer systems mitigating its frequency, visibility, and consequences,” the experts advise, using three steps: making errors more visible when they occur so their effects can be intercepted; having remedies at hand to rescue patients; and making errors less frequent by following principles that take human limitations into account.

For instance, instead of simply requiring cause of death, they suggest that death certificates could contain an extra field asking whether a preventable complication stemming from the patient’s medical care contributed to the death. Another strategy would be for hospitals to carry out a rapid and efficient independent investigation into deaths to determine the potential contribution of error.

Measuring the consequences of medical care on patient outcomes “is an important prerequisite to creating a culture of learning from our mistakes, thereby advancing the science of safety and moving us closer towards creating learning health systems,” they add.

“Sound scientific methods, beginning with an assessment of the problem, are critical to approaching any health threat to patients,” they write. “The problem of medical error should not be exempt from this scientific approach.”

And they call for “more appropriate recognition of the role of medical error in patient death to heighten awareness and guide both collaborations and capital investments in research and prevention.”

Abstract of Medical error—the third leading cause of death in the US

The annual list of the most common causes of death in the United States, compiled by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), informs public awareness and national research priorities each year. The list is created using death certificates filled out by physicians, funeral directors, medical examiners, and coroners. However, a major limitation of the death certificate is that it relies on assigning an International Classification of Disease (ICD) code to the cause of death.1 As a result, causes of death not associated with an ICD code, such as human and system factors, are not captured. The science of safety has matured to describe how communication breakdowns, diagnostic errors, poor judgment, and inadequate skill can directly result in patient harm and death. We analyzed the scientific literature on medical error to identify its contribution to US deaths in relation to causes listed by the CDC.