What just happened? Why some of us seem totally spaced out

October 7, 2011 by Amara D. Angelica

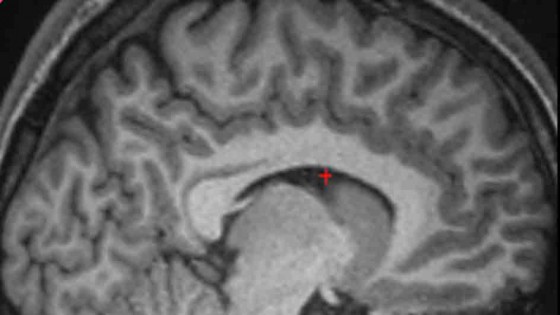

fMRI of individual without a paracingulate sulcus (credit: Jon Simons)

Ever wonder why uncle Louie seems to imagine stuff that didn’t happen, and calls you crazy? Well now’s there’s an explanation.

Half of you won’t like it, I warn you.

A new study of the brain by University of Cambridge scientists explains why some people can’t tell the difference between what they saw and what they imagined or were told about — such as whether they or another person said something, or whether an event was imagined or actually occurred.

Turns out it results from a normal variation in a fold at the front of the brain called the paracingulate sulcus (PCS), the scientists said.

Who you gonna believe? Me, or your lying memory?

This brain variation is present in roughly half of the normal population. It’s one of the last structural folds to develop before birth, so it varies greatly in size between individuals in the healthy population. The researchers discovered that adults whose MRI scans indicated an absence of the PCS were significantly less accurate on memory tasks than people with a prominent PCS on at least one side of the brain.

Interestingly, all participants believed that they had a good memory despite one group’s memories being clearly less reliable. OK, but the question is: if you explain this to them, do they back off from their alleged memories?

“Additionally, this finding might tell us something about schizophrenia, in which hallucinations are often reported whereby, for example, someone hears a voice when nobody’s there,” said Dr. Jon Simons from the University of Cambridge’s Department of Experimental Psychology and Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience Institute. “Difficulty distinguishing real from imagined information might be an explanation for such hallucinations.”

That might explain UFOs. (Especially if they watched Close Encounters of the Third Kind one too many times.)

Take this MRI test (if you dare)

For the study, the researchers recruited 53 healthy volunteers based on their brain scans which showed either a clear presence or absence of the PCS in the left or right brain hemisphere. Participants were presented either with well-known word-pairs like “Laurel and Hardy” or with the first word of a word-pair and a question mark (“Laurel and ?”). In the latter condition, participants were instructed to imagine the second word of the word-pair. Then, either they or the experimenter was instructed to read the word-pair out aloud.

After a delay, a memory test was given where participants tried to remember whether they had seen or imagined the second word of each previously-encountered word-pair, or whether they or the experimenter had read the word-pair out aloud. Participants with absence of the PCS in both brain hemispheres scored significantly worse than the others at remembering both kinds of detail.

Hmm, shouldn’t courts do an MRI test for witnesses? I’m just sayin’.

Ref.: Marie Buda, Alex Fornito, Zara M. Bergström, and Jon S. Simons, A Specific Brain Structural Basis for Individual Differences in Reality Monitoring, Journal of Neuroscience, Oct. 5, 2011, 31(40):14308-14313;doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3595-11.2011