Why don’t we have fusion yet?

October 2, 2013

The preamplifiers of the National Ignition Facility. The unified lasers deliver 1.8 megajoules of energy and 500 terawatts of power — 1,000 times more than the United States uses at any one moment. (Credit: Damien Jemison/LLNL)

The dream of igniting a self-sustained fusion reaction with high yields of energy, a feat likened to creating a miniature star on Earth, is getting closer to becoming reality, according the authors of a new review article in the journal Physics of Plasmas.

Researchers at the National Ignition Facility (NIF) report that while there is at least one significant obstacle to overcome before achieving the highly stable precisely directed implosion required for ignition, they have met many of the demanding challenges leading up to that goal since experiments began in 2010.

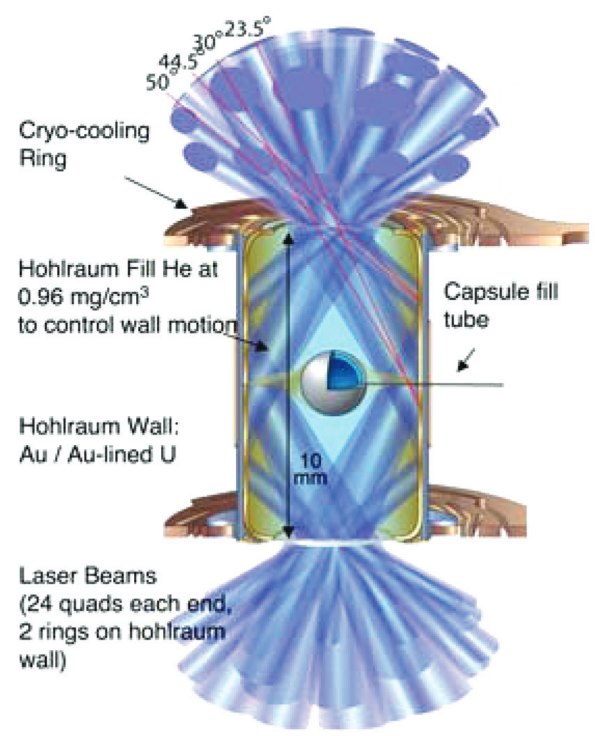

To reach ignition (defined as the point at which the fusion reaction produces more energy than is needed to initiate it), the NIF focuses 192 laser beams simultaneously in billionth-of-a-second pulses inside a cryogenically cooled hohlraum (from the German word for “hollow room”), a hollow cylinder the size of a pencil eraser.

Within the hohlraum is a ball-bearing-size capsule containing two hydrogen isotopes, deuterium and tritium (D-T). The unified lasers deliver 1.8 megajoules of energy and 500 terawatts of power — 1,000 times more than the United States uses at any one moment — to the hohlraum, creating an “X-ray oven” that implodes the D-T capsule to temperatures and pressures similar to those found at the center of the sun.

“What we want to do is use the X-rays to blast away the outer layer of the capsule in a very controlled manner.

That’s so the D-T pellet is compressed to just the right conditions to initiate the fusion reaction,” explained John Edwards, NIF associate director for inertial confinement fusion and high-energy-density science.

One major hurdle

“In our new review article, we report that the NIF has met many of the requirements believed necessary to achieve ignition — sufficient X-ray intensity in the hohlraum, accurate energy delivery to the target and desired levels of compression — but that at least one major hurdle remains to be overcome: the premature breaking apart of the capsule.”

In the article, Edwards and his colleagues discuss how they are using diagnostic tools developed at NIF to determine likely causes for the problem. “In some ignition tests, we measured the scattering of neutrons released and found different strength signals at different spots around the D-T capsule,” Edwards said.

“This indicates that the shell’s surface is not uniformly smooth and that in some places, it’s thinner and weaker than in others. In other tests, the spectrum of X-rays emitted indicated that the D-T fuel and capsule were mixing too much — the results of hydrodynamic instability — and that can quench the ignition process.”

Edwards said that the team is concentrating its efforts on NIF to define the exact nature of the instability and use the knowledge gained to design an improved, sturdier capsule. Achieving that milestone, he said, should clear the path for further advances toward laboratory ignition.

The project is led by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and includes partners from the University of Rochester’s Laboratory for Laser Energetics, General Atomics, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Sandia National Laboratory, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The article, “Progress toward ignition on the National Ignition Facility” by M.J. Edwards et al. appears in the journal Physics of Plasmas. Authors of this paper are affiliated with Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, General Atomics in San Diego, Calif., the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the University of Rochester, Los Alamos National Laboratory, and Sandia National Laboratory.

Physics of Plasmas, produced by AIP Publishing with the cooperation of the American Physical Society (APS) Division of Plasma Physics, is devoted to original experimental and theoretical contributions to the physics of plasmas.