Your virtual avatar can impact your real-world behavior, researchers suggest

February 13, 2014

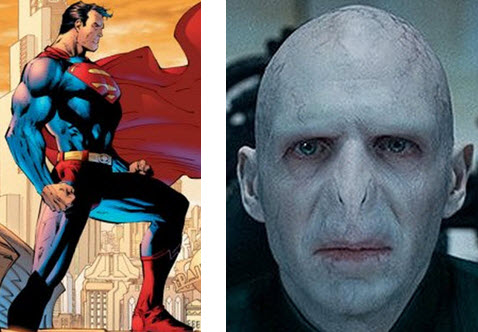

Could playing these characters in a video game affect your subsequent behavior differently? (Credit: Jim Lee and Scott Williams/DC Comics and Warner Bros. Pictures)

How you represent yourself in the virtual world of video games may affect how you behave toward others in the real world, new University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign research published in Psychological Science suggests.

“Our results indicate that just five minutes of role-play in virtual environments as either a hero or villain can easily cause people to reward or punish anonymous strangers,” says lead researcher Gunwoo Yoon.

The researchers recruited 194 undergraduates to participate in two supposedly unrelated studies. The participants were randomly assigned to play as Superman (a heroic avatar), Voldemort (a villainous avatar), or a circle (a neutral avatar).

They played a game for 5 minutes in which they, as their avatars, were tasked with fighting enemies. Then, in a presumably unrelated study, they participated in a blind taste test. They were asked to taste and then give either chocolate or chili sauce to a future participant. They were told to pour the chosen food item into a plastic dish and that the future participant would consume all of the food provided.

The results were revealing: Participants who played as Superman poured, on average, nearly twice as much chocolate as chili sauce for the “future participant.” And they poured significantly more chocolate than those who played as either of the other avatars.

Participants who played as Voldemort, on the other hand, poured out nearly twice as much of the spicy chili sauce than they did chocolate, and they poured significantly more chili sauce compared to the other participants.

A second experiment with 125 undergraduates confirmed these findings and showed that actually playing as an avatar yielded stronger effects on subsequent behavior than just watching someone else play as the avatar.

Interestingly, the degree to which participants actually identified with their avatar didn’t seem to play a role. “These behaviors occur despite modest, equivalent levels of self-reported identification with heroic and villainous avatars, alike,” Yoon and Vargas note. “People are prone to be unaware of the influence of their virtual representations on their behavioral responses.”

The researchers hypothesize that arousal — the degree to which participants are “keyed into” the game — might be an important factor driving the behavioral effects they observed.

The findings, though preliminary, may have implications for social behavior, the researchers argue:

“In virtual environments, people can freely choose avatars that allow them to opt into or opt out of a certain entity, group, or situation,” says Yoon. “Consumers and practitioners should remember that powerful imitative effects can occur when people put on virtual masks.”