A robot with two extra fingers helps you grip stuff

July 23, 2014

MIT researchers have developed a robot that enhances the grasping motion of the human hand.

The device, worn around your wrist, works like two extra fingers adjacent to the pinky and thumb.

A novel control algorithm enables it to move in sync with the wearer’s fingers to grasp objects of various shapes and sizes. Wearing the robot, a user could use one hand to hold the base of a bottle while twisting off its cap with the same hand.

“This is a completely intuitive and natural way to move your robotic fingers,” says Harry Asada, the Ford Professor of Engineering in MIT’s Department of Mechanical Engineering. “You do not need to command the robot, but simply move your fingers naturally. Then the robotic fingers react and assist your fingers.”

Ultimately, Asada says, with some training, people may come to perceive the robotic fingers as part of their body — “like a tool you have been using for a long time, you feel the robot as an extension of your hand.” He hopes that the two-fingered robot may assist people with limited dexterity in performing routine household tasks, such as opening jars and lifting heavy objects. He and graduate student Faye Wu presented a paper on the robot this week at the Robotics: Science and Systems conference in Berkeley, Calif.

Biomechanical synergy

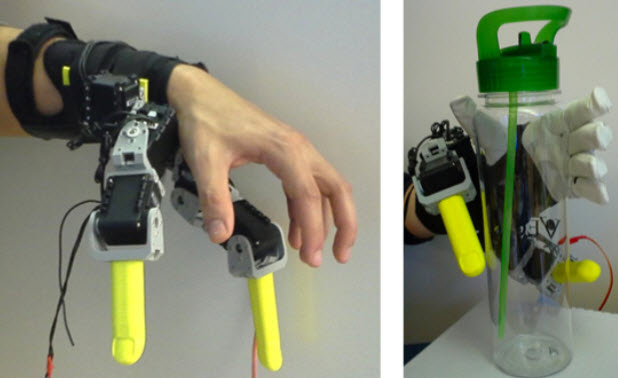

Left: prototype of the two robotic fingers mounted on the human wrist. Right: grasping experiment of the 7-fingered hand was conducted using a data glove(credit: Harry Asad and Faye Wu)

The robot, which the researchers have dubbed “supernumerary robotic fingers,” consists of actuators linked together to exert forces as strong as those of human fingers during a grasping motion.

To develop an algorithm to coordinate the robotic fingers with a human hand, the researchers first looked to the physiology of hand gestures, learning that a hand’s five fingers are highly coordinated.

While a hand may reach out and grab an orange in a different way than, say, a mug, just two general patterns of motion are used to grasp objects: bringing the fingers together, and twisting them inwards. A grasp of any object can be explained through a combination of these two patterns.

The researchers hypothesized that a similar “biomechanical synergy” may exist among seven fingers. The tested this and found that every grasp could be explained by a combination of two or three general patterns among all seven fingers.

The researchers used this information to develop a control algorithm to correlate the postures of the two robotic fingers with those of the five human fingers. The algorithm essentially “teaches” the robot to assume a certain posture that the human expects the robot to take.

MIT | Researchers at MIT have developed a device, worn around the wrist, that enhances the grasping motion of the human hand with two robotic fingers. (Video credit: Melanie Gonick/MIT)

Bringing robots closer to humans

The 7-fingered hand can perform tasks that would usually require two hands, such as holding up a tablet computer and typing letters on it (credit: Harry Asad and Faye Wu)

For now, the robot mimics the grasping of a hand, closing in and spreading apart in response to a human’s fingers. But Wu would like to take the robot one step further, controlling not just position, but also force.

Wu also notes that certain gestures — such as grabbing an apple — may differ slightly from person to person, and ultimately, a robotic aid may have to account for personal grasping preferences. To that end, she envisions developing a library of human and robotic gesture correlations. As a user works with the robot, it could learn to adapt to match his or her preferences, discarding others from the library. She likens this machine learning to that of voice-command systems, like Apple’s Siri.

“After you’ve been using it for a while, it gets used to your pronunciation so it can tune to your particular accent,” Wu says. “Long-term, our technology can be similar, where the robot can adjust and adapt to you.”

“This is breaking new ground on the question of how humans and robots interact,” says Matthew Mason, director of the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University, who was not involved in the research. “It is a novel vision, and adds to the many ways that robotics can change our perceptions of ourselves.”

Down the road, Asada says the robot may also be scaled down to a less bulky form. “Wearable robots are a way to bring the robot closer to our daily life.”