in printfrom:

September 1, 2019

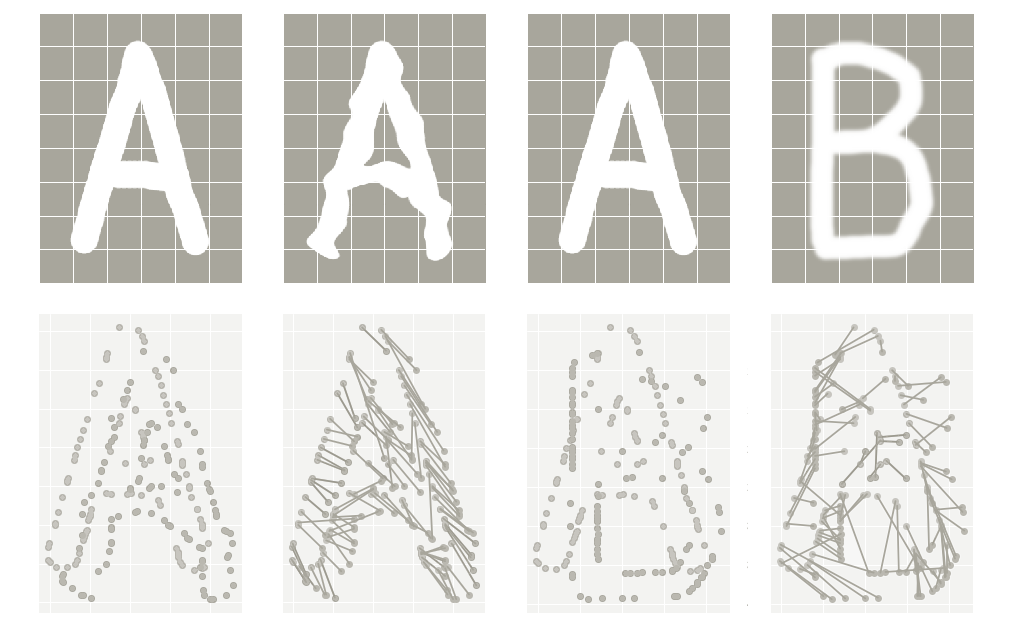

image | above

An example of computer optical character recognition.

art: Andrey Nikishaev

quick steps | for changing text size

on a personal computer with Microsoft Windows -or- Google Chrome

• on your keyboard — hold down button labeled control • (ctrl)

• at same time — hold down the plus sign (+) to increase

• at same time — hold down the minus sign (-) to decrease

on a personal computer by Apple

• on your keyboard — hold down button labeled command • (cmd)

• at same time — hold down the plus sign (+) to increase

• at same time — hold down the minus sign (-) to decrease

story |

publication: Forbes

story title: The future of OCR is machine learning

section: Forbes Technology Council

author: by Abhinav Somani

date: September 2019

introduction |

by Abhinav Somani

Whether it’s auto-extracting information from a scanned receipt for an expense report — or translating a foreign language using your smartphone’s camera, optical character recognition (OCR) tech can seem mesmerizing. And while it seems miraculous that we have computers that can digitize analog text with accuracy, the accuracy expect falls short of what’s possible.

And that’s because — despite the perception of OCR as a leap forward — it’s actually old-fashioned + limited. Largely because it’s run by an oligopoly that’s holding back further innovation.

What’s new is old.

OCR’s pre-cursor was invented over 100 years ago in Birmingham, England by the scientist Edmund Edward Fournier d’Albe. He wanted to help blind people “read” text — so d’Albe built a device called the Optophone. It used photo sensors to detect black print and then convert it into sounds.

Nature | story :: the Octophone: an instrument for reading by ear

The sounds could then be translated into words by the visually impaired reader. The device proved so expensive — and the process of reading so slow — that the potentially revolutionary Optophone was never commercially viable.

Additional development of text-to-sound continued in the early 20th century. But OCR as we know it today, didn’t get off the ground until the 1970s — when inventor + futurist Ray Kurzweil developed an OCR computer program. By year 1980, Kurzweil sold to Xerox, who continued to commercialize paper-to-computer text conversion.

Since then, very little has changed. You convert a document to an image — then the software tries to match letters against character sets that have been uploaded by a human operator.

And that’s the problem with OCR as we know it. There are countless variations in document and text types — but most OCR is built on a limited set of existing rules that ultimately limit the tech’s true utility. As character Morpheus from the Matrix film series said: “Yet their strength and their speed are still based in a world that is built on rules. Because of that, they will never be as strong or as fast as you can be.”

Innovation in OCR has been stymied by tech gatekeepers — and its few-cents-per-page business model. This makes investing billions in its development non-viable.

report |

group: Grand View Research

report title: Optical Character Recognition

deck: A report on market size, share, and trends analysis.

years: 2019 — 2025

• by type — software, services

• by vertical — retail, finance, government, education, health care

• by region

• by segment forecasts

read | report

The next generation of OCR.

But that’s starting to change. Recently, a new generation of engineers is rebooting OCR. Built using artificial intelligence based machine learning tech, these new devices aren’t limited by rules-based character matching of existing OCR software. With machine learning, algorithms trained on a significant volume of data learn to think for themselves. Instead of being restricted to a fixed number of character sets, new OCR programs can accumulate knowledge — and learn to recognize any number of characters.

One of the best examples of modern OCR: is the 34 year-old OCR software that was adopted by Google and turned open source in year 2006. Since then, the OCR community’s brightest minds have been working to improve the software’s stability. A dozen years later, Tesseract can process text in 100 languages — including right-to-left languages such as Arabic + Hebrew.

Open Source | story • Google’s Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software works for 248+ languages

Amazon also released a powerful OCR engine called Textract. Made available through Amazon Web Services, the product already has a positive reputation for accuracy.

These readily available technologies have vastly reduced the cost of building an OCR with enhanced quality. Still, they don’t solve the problems that most OCR users are hoping to fix.

Looking to deep learning.

The historic, intrinsic difficulty of character recognition has blinded us to the reality that simple digitization was never the end goal for using OCR. We don’t use OCR just so we can put analog text into digital formats. What we want is to turn analog text into digital insights. For example, a company might scan 100s of insurance contracts — with the end goal of uncovering its climate-risk exposure. But turning all those paper contracts into digital ones is only bit more useful than the originals.

That’s why we’re looking beyond machine learning — implementing another type of artificial intelligence: deep learning. In deep learning, a neural network mimics the function of a human mind, ensuring algorithms don’t have to rely on historic patterns to determine accuracy — they can do it themselves. The benefit is — with deep learning — the techdoes more than just recognize text. It can derive meaning from it.

With deep learning OCR, the company scanning insurance contracts gets more than just digital versions of their paper documents. They get instant visibility into the meaning of the text in those documents. And that can unlock billions of dollars worth of insights + saved time.

Adding insight to recognition.

OCR is finally moving away from just seeing + matching. Driven by deep learning, it’s entering a new phase where the software first recognizes scanned text, then makes meaning of it. Products with the competitive edge will provide the most powerful info extraction — plus highest quality insights.

And since each business category has its own particular document types, structures, and considerations — there’s room for multiple companies to succeed based on vertical-specific competency.

Users of traditional OCR services should re-evaluate their current licenses + payment terms. They can also try free services such as: Textract by Amazon — or Tesseract by Google — to see the latest advances in OCR.

It’s also important to scope independent providers in robotic process automation + AI who are making strides for the industry. In 5 years: I expect what’s been mostly static for the past 30 years — if not 100 — will be completely unrecognizable.

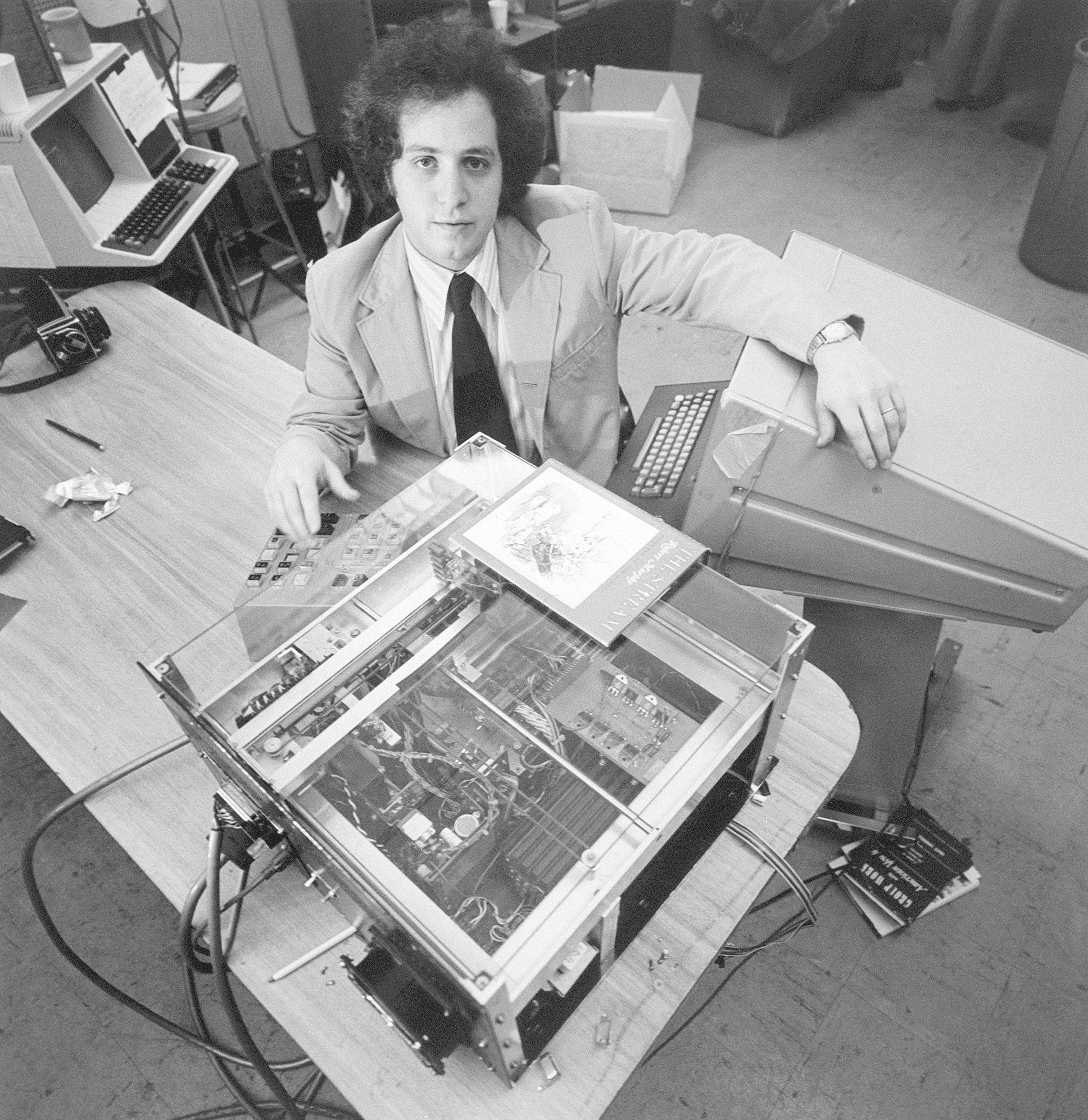

special section | historic photos

Ray Kurzweil and the reading machine for the blind.

from: the Kurzweil Library

photo | no. 1

about: Ray Kurzweil with the Reading Machine for the Blind.

detail: A close-up of the full machine.

year: 1976

photo | no. 2

about: Ray Kurzweil with his invention the Reading Machine for the Blind.

detail: A close-up of the internal scanner for printed books, letters, reports, periodicals.

year: 1976

— notes —

OCR = optical character recognition