Harnessing electricity from low-power sources in the environment

September 15, 2011

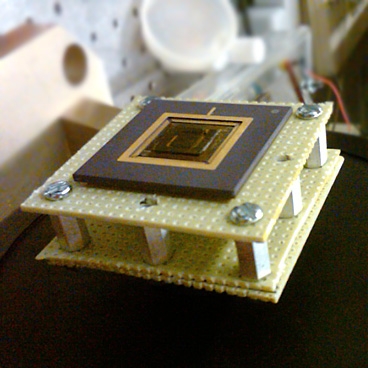

A new energy-harvesting device converts low-frequency vibrations into electricity, shown mounted on a stand (credit: Arman Hajati)

Researchers at MIT have designed a device the size of a U.S. quarter that harvests energy from low-frequency vibrations, such as those that might be felt along a pipeline or bridge.

Today’s wireless-sensor networks can do many things from supervising factory machinery to tracking environmental pollution to measuring the movement of buildings and bridges, but power is one limiting factor to wireless sensors technology.

To get around the power constraint, the MIT researchers have harnessed electricity from low-power sources in the environment, such as vibrations from swaying bridges, humming machinery and rumbling foot traffic. Such natural energy sources could do away with the need for batteries, powering wireless sensors indefinitely. The tiny energy harvester — known technically as a microelectromechanical system, or MEMS — picks up a wider range of vibrations than current designs, and is able to generate 100 times the power of devices of similar size.

“There are wireless sensors widely available, but there is no supportive power package,” says Sang-Gook Kim, a professor of mechanical engineering at MIT and co-author of the paper. “I think our vibrational-energy harvesters are a solution for that.”

Putting the squeeze on

To harvest electricity from environmental vibrations, researchers have typically looked to piezoelectric materials such as quartz and other crystals. Such materials naturally accumulate electric charge in response to mechanical stress (piezo, in Greek, means to squeeze or press). In the past few years, researchers have exploited piezoelectric material, or PZT, at the microscale, engineering MEMS devices that generate small amounts of power.

Various groups have gravitated toward a common energy-harvesting design: a small microchip with layers of PZT glued to the top of a tiny cantilever beam. As the chip is exposed to vibrations, the beam moves up and down like a wobbly diving board, bending and stressing the PZT layers. The stressed material builds up an electric charge, which can be picked up by arrays of tiny electrodes.

However, the cantilever-based approach comes with a significant limitation. The beam itself has a resonant frequency — a specific frequency at which it wobbles the most. Outside of this frequency, the beam’s wobbling response drops off, along with the amount of power that can be generated.

So the researchers came up with a design that increases the device’s frequency range, or bandwidth, while maximizing the power density, or energy generated per square centimeter of the chip. Instead of taking a cantilever-based approach, the team went a slightly different route, engineering a microchip with a small bridge-like structure that’s anchored to the chip at both ends. The researchers deposited a single layer of PZT to the bridge, placing a small weight in the middle of it.

The team then put the device through a series of vibration tests, and found it was able to respond not just at one specific frequency, but also at a wide range of other low frequencies. The researchers calculated that the device was able to generate 45 microwatts of power with just a single layer of PZT — an improvement of two orders of magnitude compared to current designs.

“Our target is at least 100 microwatts, and that’s what all the electronics guys are asking us to get to,” says Hajati, now a MEMS development engineer at FujiFilm Dimatix in Santa Clara, Calif. “For monitoring a pipeline, if you generate 100 microwatts, you can power a network of smart sensors that can talk forever with each other, using this system.”

Ref.: Arman Hajati and Sang-Gook Kim, Ultra-wide bandwidth piezoelectric energy harvesting, Applied Physics Letters, 2011; [DOI:10.1063/1.3629551]