More evidence that you’re a mindless robot with no free will

May 4, 2016

(credit: iStock)

The results of two Yale University psychology experiments suggest that what we believe to be a conscious choice may actually be constructed, or confabulated, unconsciously after we act — to rationalize our decisions. A trick of the mind.

“Our minds may be rewriting history,” said Adam Bear, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Psychology and lead author of a paper published April 28 in the journal Psychological Science.

Tricks of the mind

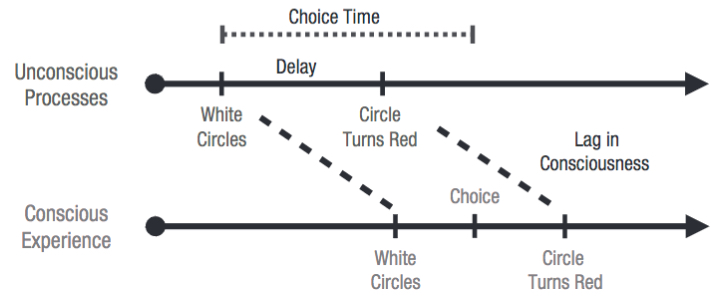

A model of “postdictive” choice. Although choice of a circle is not actually completed until after a circle has turned red, the choice may seem to have occurred before that event because the participant has not yet become conscious of the circle’s turning red. The circle’s turning red can therefore unconsciously bias a participant’s choice when the delay is sufficiently short. (credit: Adam Bear and Paul Bloom/Psychological Science)

Bear and Paul Bloom performed two simple experiments to test how we experience choices. In one experiment, participants were told that five white circles would appear on the computer screen in front of them and, in rapid-fire sequence, one would turn red. They were asked to predict which one would turn red and mentally note this. After a circle turned red, participants then recorded by keystroke whether they had chosen correctly, had chosen incorrectly, or had not had time to complete their choice.

The circle that turned red was always selected by the system randomly, so probability dictates that participants should predict the correct circle 20% of the time. But when they only had a fraction of a second to make a prediction, these participants were likely to report that they correctly predicted which circle would change color more than 20% of the time.

In contrast, when participants had more time to make their guess — approaching a full second — the reported number of accurate predictions dropped back to expected levels of 20% success, suggesting that participants were not simply lying about their accuracy to impress the experimenters.

(In a second experiment to eliminate artifacts, participants chose one of two different-colored circles, with similar results.)

Confabulating reality

What happened, Bear suggests, is that events were rearranged in subjects’ minds: People unconsciously perceived the color red from the screen image before they predicted it would appear, but then right after that, consciously experienced these two things in the opposite order.

Bear said it is unknown whether this “postdictive” illusion is caused by a quirk in perceptual processing that can only be reproduced in the lab, or whether it might have “far more pervasive effects on our everyday lives and sense of free will.”

Previous research at Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin suggests the latter, and includes volition. That research involved a “duel” game between a human and a brain-computer interface (see Do we have free will?). It showed that there‘s a “point of no return” in the decision-making process (at about 200 milliseconds before actual movement onset), after which cancellation of a person’s movement is no longer possible.

Abstract of A Simple Task Uncovers a Postdictive Illusion of Choice

Do people know when, or whether, they have made a conscious choice? Here, we explore the possibility that choices can seem to occur before they are actually made. In two studies, participants were asked to quickly choose from a set of options before a randomly selected option was made salient. Even when they believed that they had made their decision prior to this event, participants were significantly more likely than chance to report choosing the salient option when this option was made salient soon after the perceived time of choice. Thus, without participants’ awareness, a seemingly later event influenced choices that were experienced as occurring at an earlier time. These findings suggest that, like certain low-level perceptual experiences, the experience of choice is susceptible to “postdictive” influence and that people may systematically overestimate the role that consciousness plays in their chosen behavior.