NASA develops super-black material that absorbs light across multiple wavelength bands

November 10, 2011

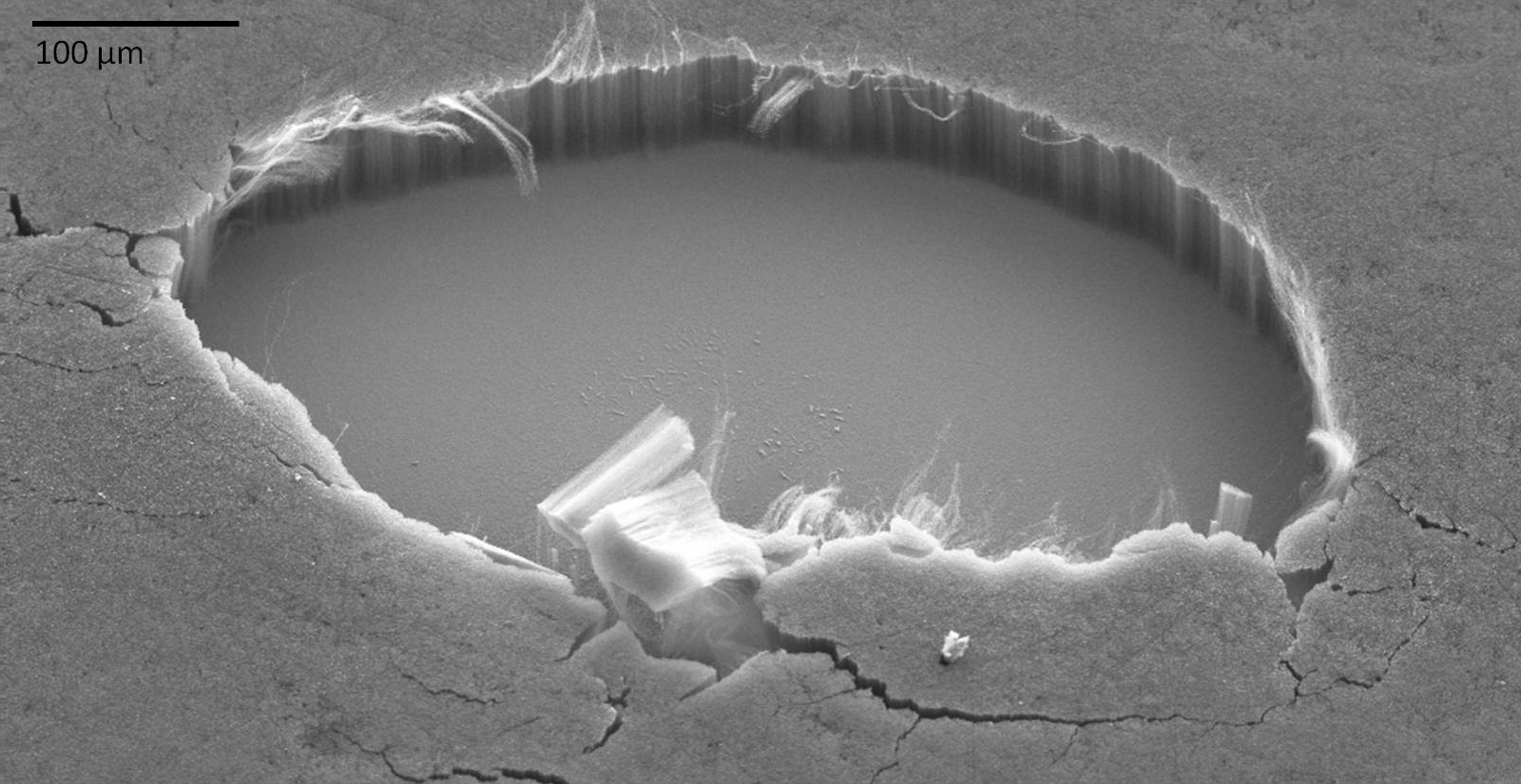

This close-up view (about 0.03 inches wide) shows the internal structure of a carbon-nanotube coating that absorbs about 99 percent of the ultraviolet, visible, infrared, and far-infrared light that strikes it. A section of the coating, which was grown on smooth silicon, was purposely removed to show the tubes' vertical alignment. (Credit: Stephanie Getty, NASA Goddard)

Engineers at NASA‘s Goddard Space Flight Center have produced a material that absorbs more than 99 percent of the ultraviolet, visible, infrared, and far-infrared light that hits it.

The nanotech-based coating is a thin layer of multi-walled carbon nanotubes. They are positioned vertically on various substrate materials much like a shag rug. The team has grown the nanotubes on silicon, silicon nitride, titanium, and stainless steel, materials commonly used in space-based scientific instruments.

The tests indicate that the nanotube material is especially useful for a variety of spaceflight applications where observing in multiple wavelength bands is important to scientific discovery. One such application is stray-light suppression. The tiny gaps between the tubes collect and trap background light to prevent it from reflecting off surfaces and interfering with the light that scientists actually want to measure. Because only a small fraction of light reflects off the coating, the human eye and sensitive detectors see the material as black.

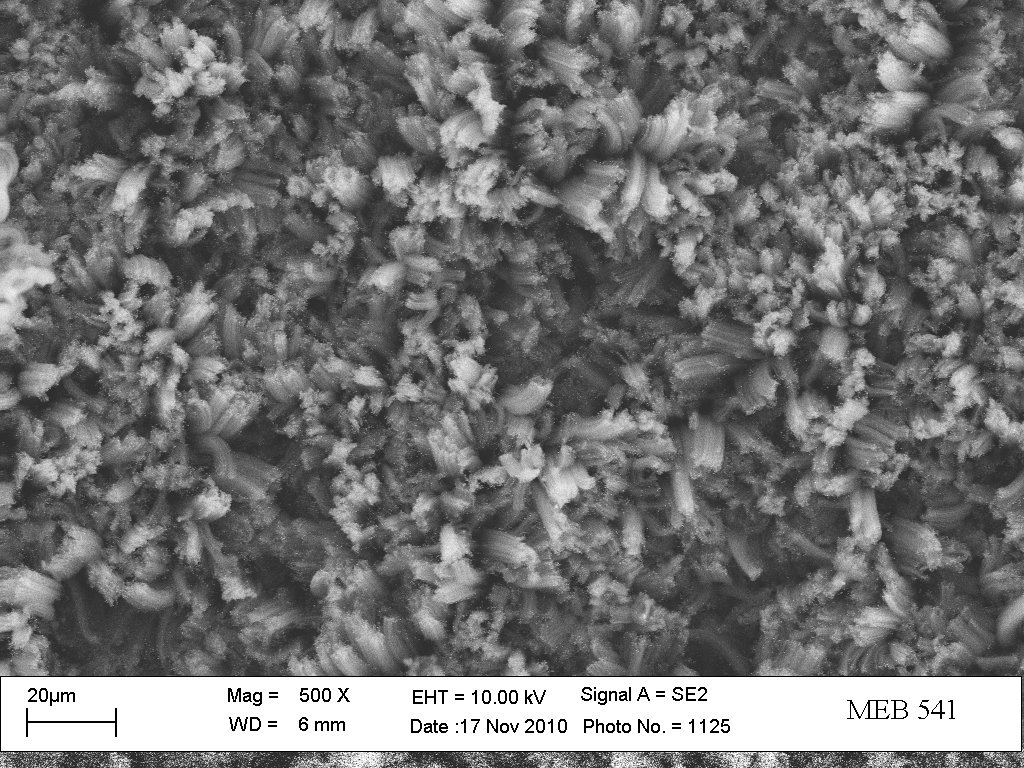

The material is 10 to 100 times more absorbent than other materials, depending on the specific wavelength band. It absorbs 99.5 percent of the light in the ultraviolet and visible, and 98 percent in the longer or far-infrared bands.

This high-magnification image, taken with an electron microscope, shows an even closer view of the hollow carbon nanotubes. A coating made of this material is seen as black by the human eye and sensitive detectors because the tiny gaps between the tubes collect and trap light, preventing reflection.(Credit: Stephanie Getty, NASA Goddard)

If used in detectors and other instrument components, the technology would allow scientists to gather hard-to-obtain measurements of objects so distant in the universe that astronomers no longer can see them in visible light or those in high-contrast areas, including planets in orbit around other stars. Earth scientists studying the oceans and atmosphere also would benefit. More than 90 percent of the light Earth-monitoring instruments gather comes from the atmosphere, overwhelming the faint signal they are trying to retrieve.

Currently, instrument developers apply black paint to baffles and other components to help prevent stray light from ricocheting off surfaces. However, black paints absorb only 90 percent of the light that strikes it. The effect of multiple bounces makes the coating’s overall advantage even larger, potentially resulting in hundreds of times less stray light.

In addition, black paints do not remain black when exposed to cryogenic temperatures. They take on a shiny, slightly silver quality, said Goddard scientist Ed Wollack, who is evaluating the carbon-nanotube material for use as a calibrator on far-infrared-sensing instruments that must operate in super-cold conditions to gather faint far-infrared signals emanating from objects in the very distant universe. If these instruments are not cold, thermal heat generated by the instrument and observatory, will swamp the faint infrared they are designed to collect.

Black materials also serve another important function on spacecraft instruments, particularly infrared-sensing instruments. The blacker the material, the more heat it radiates away. In other words, super-black materials, like the carbon nanotube coating, can be used on devices that remove heat from instruments and radiate it away to deep space. This cools the instruments to lower temperatures, where they are more sensitive to faint signals.