Researchers create miniature human retina in a dish

June 11, 2014

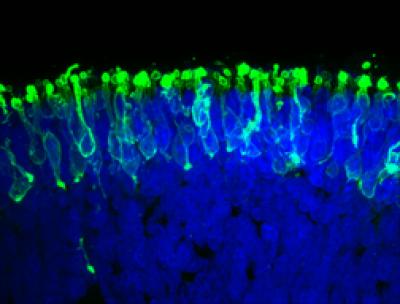

These are rod photoreceptors (in green) within a “mini retina” derived from human iPS cells in the lab (credit: Johns Hopkins Medicine)

Johns Hopkins researchers have created a miniature human retina in a dish that can sense light.

The work, reported online June 10 in the journal Nature Communications, “advances opportunities for vision-saving research and may ultimately lead to technologies that restore vision in people with retinal diseases,” says study leader M. Valeria Canto-Soler, Ph.D., an assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The achievement emerged from experiments with human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPS). While the system doesn’t yet produce images, it could eventually enable genetically engineered retinal cell transplants that halt or even reverse a patient’s march toward blindness, the researchers say.

The iPS cells are adult cells that have been genetically reprogrammed to their most primitive state. Under the right circumstances, they can develop into most or all of the 200 cell types in the human body. In this case, the Johns Hopkins team turned them into retinal progenitor cells destined to form light-sensitive retinal tissue that lines the back of the eye.

Canto-Soler says that the newly developed system gives them the ability to generate hundreds of mini-retinas at a time directly from a person affected by a particular retinal disease such as retinitis pigmentosa. This provides a unique biological system to study the cause of retinal diseases directly in human tissue, instead of relying on animal models.

Personalized retinal treatment to restore vision

The system, she says, also opens an array of possibilities for personalized medicine such as testing drugs to treat these diseases in a patient-specific way. In the long term, the potential is also there to replace diseased or dead retinal tissue with lab-grown material to restore vision.

Retinal tissue is complex, comprising seven major cell types, including six kinds of neurons, which are all organized into specific cell layers that absorb and process light, “see,” and transmit those visual signals to the brain for interpretation. The lab-grown retinas recreate the three-dimensional architecture of the human retina.

“We knew that a 3-D cellular structure was necessary if we wanted to reproduce functional characteristics of the retina,” says Canto-Soler, “but when we began this work, we didn’t think stem cells would be able to build up a retina almost on their own. In our system, somehow the cells knew what to do.”

When the retinal tissue was at a stage equivalent to 28 weeks of development in the womb, with fairly mature photoreceptors, the researchers tested these mini-retinas to see if the photoreceptors could in fact sense and transform light into visual signals.

They did so by placing an electrode into a single photoreceptor cell and then giving a pulse of light to the cell, which reacted in a biochemical pattern similar to the behavior of photoreceptors in people exposed to light.

Specifically, she says, the lab-grown photoreceptors responded to light the way retinal rods do. Human retinas contain two major photoreceptor cell types called rods and cones. The vast majority of photoreceptors in humans are rods, which enable vision in low light. The retinas grown by the Johns Hopkins team were also dominated by rods.

Purdue University University of Wisconsin researchers also contributed to the work.

This research was supported by grants from the Maryland Stem Cell Research Fund; the William and Ella Owens Medical Research Foundation; The J. Willard and Alice S. Marriott Foundation; the William and Mary Greve Special Scholar Award from Research to Prevent Blindness, and the National Institutes of Health’s National Eye Institute.

Abstract of Nature Communications paper

Many forms of blindness result from the dysfunction or loss of retinal photoreceptors. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) hold great potential for the modelling of these diseases or as potential therapeutic agents. However, to fulfill this promise, a remaining challenge is to induce human iPSC to recreate in vitro key structural and functional features of the native retina, in particular the presence of photoreceptors with outer-segment discs and light sensitivity.

Here we report that hiPSC can, in a highly autonomous manner, recapitulate spatiotemporally each of the main steps of retinal development observed in vivo and form three-dimensional retinal cups that contain all major retinal cell types arranged in their proper layers. Moreover, the photoreceptors in our hiPSC-derived retinal tissue achieve advanced maturation, showing the beginning of outer-segment disc formation and photosensitivity. This success brings us one step closer to the anticipated use of hiPSC for disease modelling and open possibilities for future therapies.