Researchers turn one form of neuron into another in the brain

January 22, 2013

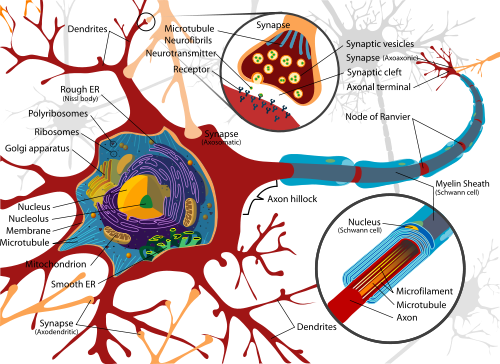

Diagram of a typical motor neuron (credit: Wikimedia Commons)

A new finding by Harvard stem cell biologists turns one of the basics of neurobiology on its head — demonstrating that it is possible to turn one type of already differentiated (formed from a stem cell) neuron into another within the brain.

The discovery by Paola Arlotta and Caroline Rouaux indicates that “maybe the brain is not as immutable as we always thought, because at least during an early window of time, one can reprogram the identity of one neuronal class into another,” said Arlotta, an Associate Professor in Harvard’s Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology (SCRB).

The principle of direct lineage reprogramming of differentiated cells within the body was first proven by SCRB co-chair and Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) co-director Doug Melton and colleagues five years ago, when they reprogrammed exocrine pancreatic cells directly into insulin producing beta cells.

Arlotta and Rouaux now have proven that neurons too can change their mind.

In their experiments, Arlotta targeted callosal projection neurons, which connect the two hemispheres of the brain, and turned them into neurons similar to corticospinal motor neurons, one of two populations of neurons destroyed in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease.

To achieve such reprogramming of neuronal identity, the researchers used a transcription factor called Fezf2, which long as been known for playing a central role in the development of corticospinal neurons in the embryo.

Implications for treatment of neurodegenerative diseases

What makes the finding even more significant is that the work was done in the brains of living mice, rather than in collections of cells in laboratory dishes. The mice were young, so researchers still do not know if neuronal reprogramming will be possible in older laboratory animals — and humans. If it is possible, this has enormous implications for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

“Neurodegenerative diseases typically effect a specific population of neurons, leaving many others untouched. For example, in ALS it is corticospinal motor neurons in the brain and motor neurons in the spinal cord, among the many neurons of the nervous system, that selectively die,” Arlotta said.

“What if one could take neurons that are spared in a given disease and turn them directly into the neurons that die off? In ALS, if you could generate even a small percentage of corticospinal motor neurons, it would likely be sufficient to recover basic functioning,” she said.

The work in Arlotta’s lab is focused on the cerebral cortex, but “it opens the door to reprogramming in other areas of the central nervous system,” she said.

Arlotta, an HSCI principal faculty member, is now working with colleague Takao Hensch, of Harvard’s Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, to explicate the physiology of the reprogrammed neurons, and learn how they communicate within pre-existing neuronal networks.

“My hope is that this will facilitate work in a new field of neurobiology that explores the boundaries and power of neuronal reprogramming to re-engineer circuits relevant to disease,” said Arlotta.

This work was financed by a seed grant from the Harvard Stem Cell Institute, and by support from the National Institutes of Health, and the Spastic Parapelgia Foundation.