Ultra-high-res 100,000 dpi color printing

April 12, 2013

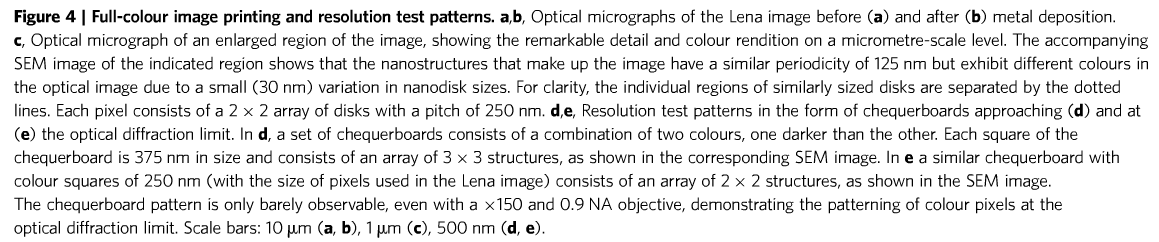

Variation in post size and spacing in the metal array alters which incoming wavelength of light (red, green or blue) is reflected back (K. Kumar et al./A*STAR)

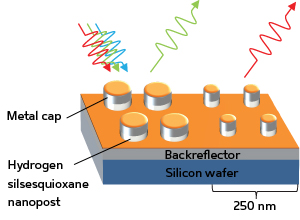

Commercial laser printers typically produce pin-sharp images with spots of ink about 20 micrometers apart, resulting in a resolution of 1,200 dots per inch (dpi).

By shrinking the separation to just 250 nanometers — 80 times smaller, a research team at A*STAR can now print images at an incredible 100,000 dpi, the highest possible resolution for a color image.

These images could be used as minuscule anti-counterfeit tags, for steganography (hidden messages in images) or nanoscale optical filters or to encode high-density data.

To print the image, the team coated a silicon wafer with insulating hydrogen silsesquioxane and then removed part of that layer to leave behind a series of upright posts of about 95 nanometers high. They capped these nanoposts with layers of chromium, silver and gold (1, 15 and 5 nanometers thick, respectively), and also coated the wafer with metal to act as a backreflector.

Each color pixel in the image contained four posts at most, arranged in a square. The researchers were able to produce a rainbow of colors simply by varying the spacing and diameter of the posts to between 50 nanometers and 140 nanometers.

When light hits the thin metal layer that caps the posts, it sends ripples — known as plasmons — running through the electrons in the metal. The size of the post determines which wavelengths of light are absorbed, and which are reflected (see image).

The plasmons in the metal caps also cause electrons in the backreflector to oscillate. “This coupling channels energy from the disks into the backreflector plane, thus creating strong absorption that results in certain colors being subtracted from the visible spectrum,” says Joel Yang, who led the team of researchers at the A*STAR Institute of Materials Research and Engineering and the A*STAR Institute of High Performance Computing.

Printing images in this way makes them potentially more durable than those created with conventional dyes. In addition, color images cannot be any more detailed: two adjacent dots blur into one if they are closer than half the wavelength of the light reflecting from them. Since the wavelength of visible light ranges about 380–780 nanometers, the nanoposts are as close as is physically possible to produce a reasonable range of colors.

Although the process takes several hours, Yang suggests that a template for the nanoposts could rapidly stamp many copies of the image. “We are also exploring novel methods to control the polarization of light with these nanostructures and approaches to improve the color purity of the pixels,” he adds.

Affiliated researchers are from the A*STAR Institute of Materials Research and Engineering and the A*STAR Institute of High Performance Computing

(Credit: K. Kumar et al./A*STAR/Nature Nanotechnology)