A ‘super-resolution’ microscope for nanostructures

May 1, 2013

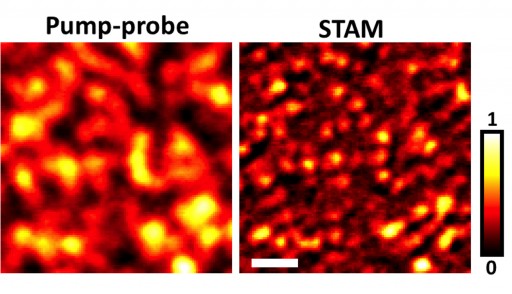

A new type of super-resolution optical microscopy takes a high-resolution image (at right) of graphite “nanoplatelets” about 100 nanometers wide. The imaging system, called saturated transient absorption microscopy, or STAM, uses a trio of laser beams and represents a practical tool for biomedical and nanotechnology research. (Credit: Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering/Purdue University)

Researchers have found a way to see synthetic nanostructures and molecules, using a new type of super-resolution optical microscopy that does not require fluorescent dyes, representing a practical tool for biomedical and nanotechnology research.

“Super-resolution optical microscopy has opened a new window into the nanoscopic world,” said Ji-Xin Cheng, an associate professor of biomedical engineering and chemistry at Purdue University.

Conventional optical microscopes can resolve objects no smaller than about 300 nanometers, or billionths of a meter, a restriction known as the “diffraction limit,” which is defined as half the width of the wavelength of light being used to view the specimen.

However, researchers want to view molecules such as proteins and lipids, as well as synthetic nanostructures like nanotubes, which are only a few nanometers in diameter.

Such a capability could bring advances in a diverse range of disciplines, from medicine to nanoelectronics, Cheng said.

“The diffraction limit represents the fundamental limit of optical imaging resolution,” Cheng said. “Stefan Hell at the Max Planck Institute and others have developed super-resolution imaging methods that require fluorescent labels. Here, we demonstrate a new scheme for breaking the diffraction limit in optical imaging of non-fluorescent species. Because it is label-free, the signal is directly from the object so that we can learn more about the nanostructure.”

Saturated transient absorption microscopy

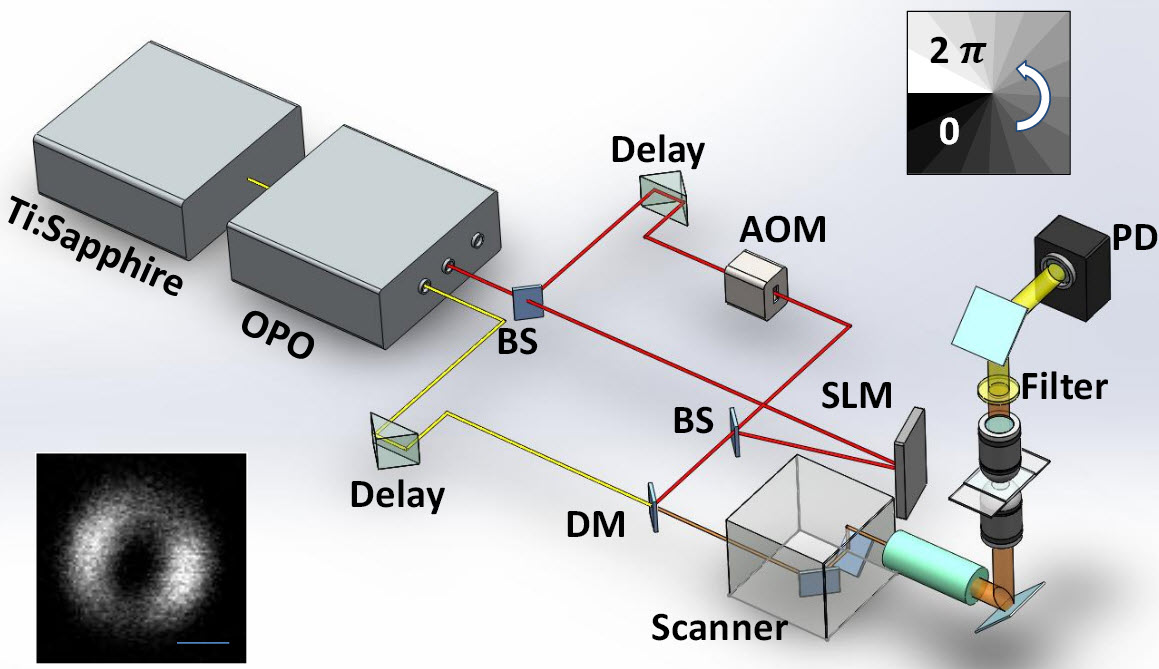

Diagram of the saturated transient absorption microscope. OPO: optical parametric oscillator; AOM: acousto-optic modulator; BS: beam splitter; SLM: spatial light modulator; PD: photodiode; DM: dichroic mirror. Upper-right inset: the helix phase pattern sent to SLM to generate doughnut shape focus of the saturation beam. Lower-left inset: the measured point spread function of the saturation beam using second harmonic imaging of 20 nm ZnO nano-crystals. Scale bar: 500nm. (Credit: Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering/Purdue University)

The imaging system, called saturated transient absorption microscopy, or STAM, uses a trio of laser beams, including a doughnut-shaped laser beam that selectively illuminates some molecules but not others. Electrons in the atoms of illuminated molecules are kicked temporarily into a higher energy level and are said to be excited, while the others remain in their “ground state.” Images are generated using a laser called a probe to compare the contrast between the excited and ground-state molecules.

The researchers demonstrated the technique, taking images of graphite “nanoplatelets” about 100 nanometers wide.

“It’s a proof of concept and has great potential for the study of nanomaterials, both natural and synthetic,” Cheng said.

The doughnut-shaped laser excitation technique, invented by researcher Stefan Hell, makes it possible to focus on yet smaller objects. Researchers hope to improve the imaging system to see objects about 10 nanometers in diameter, or about 30 times smaller than possible using conventional optical microscopes.

“We are not there yet, but a few schemes can be applied to further increase the resolution of our system,” Cheng said.

Future research may include work to use lasers with shorter wavelengths of light. Because the wavelengths are shorter, the doughnut hole is smaller, possibly allowing researchers to focus on smaller objects.

The work will be discussed during the third annual Spectroscopic Imaging: A New Window into the Unseen World workshop on May 23 and 24 at Purdue. The workshop is hosted by the university’s Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering.

The research is funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.