Breakthrough nanoparticle halts multiple sclerosis, diabetes, allergies

November 20, 2012

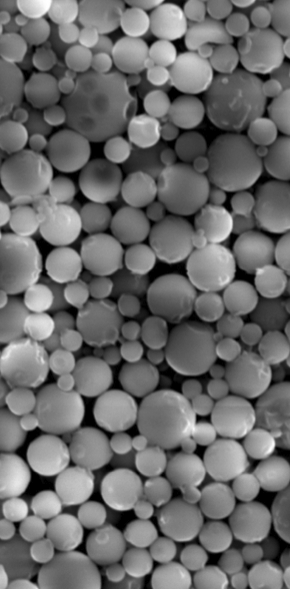

Microparticle image (credit: Daniel R. Getts et al./Northwestern University)

Northwestern Medicine researchers have developed a biodegradable nanoparticle that stealthily delivers an antigen that tricks the immune system into stopping its attack on myelin and haltd a model of relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis (MS) in mice, according to new research.

The nanoparticles can also be applied to other immune-mediated diseases, including Type 1 diabetes, food allergies, and asthma.

In MS, the immune system attacks the myelin membrane that insulates nerves cells in the brain, spinal cord, and optic nerve. When the insulation is destroyed, electrical signals can’t be effectively conducted, resulting in symptoms that range from mild limb numbness to paralysis or blindness. About 80 percent of MS patients are diagnosed with the relapsing remitting form of the disease.

The nanoparticles do not suppress the entire immune system, as do current therapies for MS, which make patients more susceptible to everyday infections and higher rates of cancer. Rather, when the nanoparticles are attached to myelin antigens and injected into the mice, the immune system is reset to normal. The immune system stops recognizing myelin as an alien invader and halts its attack on it.

“This is a highly significant breakthrough in translational immunotherapy,” said Stephen Miller, a corresponding author of the study and the Judy Gugenheim Research Professor of Microbiology-Immunology at Northwestern Feinberg School of Medicine. “The beauty of this new technology is it can be used in many immune-related diseases. We simply change the antigen that’s delivered.”

“The holy grail is to develop a therapy that is specific to the pathological immune response, in this case the body attacking myelin,” Miller added. “Our approach resets the immune system so it no longer attacks myelin, but leaves the function of the normal immune system intact.“

As effective as white blood cells

The nanoparticle was developed by Lonnie Shea, professor of chemical and biological engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and Applied Science.

The study’s method is the same approach now being tested in multiple sclerosis patients in a phase I/II clinical trial — with one key difference. The trial uses a patient’s own white blood cells — a costly and labor intensive procedure — to deliver the antigen. The purpose of the new study was to see if nanoparticles could be as effective as the white blood cells as delivery vehicles.

The nanoparticles are made from an easily produced and already FDA-approved substance, a polymer called Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLG), which consists of lactic acid and glycolic acid, both natural metabolites in the human body. PLG is most commonly used for biodegradable sutures.

The fact that PLG is already FDA approved for other applications should facilitate translating the research to patients, Shea noted. The researchers tested nanoparticles of various sizes and discovered that 500 nanometers was most effective at modulating the immune response.

Nanoparticles have many advantages: they can be readily produced in a laboratory and standardized for manufacturing; and they would make the potential therapy cheaper and more accessible to a general population.

“We administered these particles to animals who have a disease very similar to relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis and stopped it in its tracks,” Miller said. “We prevented any future relapses for up to 100 days, which is the equivalent of several years in the life of an MS patient.”

Study results

Shea and Miller also are currently testing the nanoparticles to treat Type one diabetes and airway diseases such as asthma. In the study, researchers attached myelin antigens to the nanoparticles and injected them intravenously into the mice. The particles entered the spleen, which filters the blood and helps the body dispose of aging and dying blood cells.

There, the particles were engulfed by macrophages, a type of immune cell, which then displayed the antigens on their cell surface. The immune system viewed the nanoparticles as ordinary dying blood cells and nothing to be concerned about. This created immune tolerance to the antigen by directly inhibiting the activity of myelin responsive T cells and by increasing the numbers of regulatory T cells, which further calmed the autoimmune response.

“The key here is that this antigen/particle-based approach to induction of tolerance is selective and targeted. Unlike generalized immunosuppression, which is the current therapy used for autoimmune diseases, this new process does not shut down the whole immune system,” said Christine Kelley, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering director of the division of Discovery Science and Technology at the National Institutes of Health, which supported the research.

The research is supported by a grant from the Myelin Repair Foundation and grants from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation.